ABSTRACT: The dance of the gentle pass, the aggression of a... two companies in the period between negotiations and closing; while...

advertisement

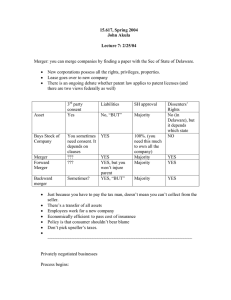

Julia Crowley Mergers and Acquisitions Palmiter Spring 2014 May 7, 2014 ABSTRACT: The dance of the gentle pass, the aggression of a bear hug, the balancing act of two companies in the period between negotiations and closing; while it can be done many ways, there is definitely an art in bringing two companies together under U.S. merger law. In 2000, General Electric and Honeywell went through the complex and intricate process of merging their two companies, getting approval by the U.S. Department of Justice, and it seemed as if two of the US’s Fortune 500 companies would successfully become one; then the European Commission on Competition got involved. For the first time ever, the European Commission denied the merger of two U.S. companies which the U.S. government had condoned. This article will lay out the U.S. side of the proposed merger between GE and Honeywell and discuss the process and implications of the denial of the merger by the Commission. Doubling the Standards: The Impact of the European Commission veto of the GE-Honeywell Merger on U.S. Firm’s Merger Analysis General Electric (GE) is one of those U.S. companies that has its hand in every pot, and part of how this came to be is their history of merging and absorbing companies from various sectors of the economy. A company with this many past mergers must have a whole team whose only job is to identify potential targets, negotiate deals and close. GE’s Chairman, Jack Welch always has his ear to the ground for potential targets, and when he mentions in passing conversation he may want your company, its time to sit up and listen. The Honeywell merger looked like it would be just like any other, but for the first time in history, the European Commission on Competition (EC) threw a wrench in a U.S. merger that was ready to close with U.S. regulatory approval. GE may have actually dodged a bullet, the long delay in closing brought on by the EC investigation of the merger gave GE time to take a longer look at Honeywell’s prospects and allowed the market reaction to the potential merger to be fully analyzed. The real moral of the story however, was a realization by American firms that future mergers between global companies, even when both are based in the U.S., will be scrutinized by both U.S. and European authorities, and the standards by which they will be judged are not necessarily the same. Attorneys and merger specialists will need to advise their U.S. corporate clients of the potential obstacles to a successful merger by looking at both U.S. and EC requirements, and the failed GE – Honeywell merger is a perfect example of how a merger that passes one bar will not necessarily pass the other. 1 Structure of the Deal: In October of 2000, GE Chairman Jack Welch learned hat United Technologies Corporation (who, like GE, makes airplane engines under their Pratt & Whitney division) was planning to buy Honeywell International. According to Time, Welch had a counteroffer to purchase Honeywell out from under United from his board assembled in under an hour and had secured the merger with Honeywell in less than two days. Welch first heard about the deal between United and Honeywell from chatter on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange on a visit there. Honeywell had long been on the radar of GE so Welch wasted no time, crafting an offer from his board apparently in only 45 minuets and from his cell phone sitting in the car no less. The deal was done in only two days, and Welch postponed his retirement in order to see it through. The capstone to his distinguished career would be the single largest merger of two industrial companies in U.S. history. Welch was confident in the merger passing antitrust review because GE and Honeywell had very few product overlaps. Honeywell International makes advanced aviation electronics and GE, among a large number of other ventures, makes airplane engines. During negotiations with the U.S. regulators to approve the merger, GE did have to divest itself of their helicopter-engines division because that was an area of product overlap, but this kind of reorganization was part and parcel of any large merger. GE’s competition was against the merger from the get go. Rolls-Royce thought the opportunity for GE to “bundle” engine and avionics packages would be something they and United Technologies would not be able to compete with. This fear was compounded given GE’s role as a buyer of planes in their GE Capital Aviation Services (GEACS) division. While GECAS only has an 8% share of the new plane market, GEACS is frequently a launch customer for planes, this fact would prove influential, but not determinative, in the review by the EC. GE was able to overcome the arguments from competitors about the effect the merger would have on the U.S. market during their approval process with the American authorities. The same competitor complaints had very different consequences when analyzed by the European body who reviews mergers, the European Commission on Competition. The eventual denial of the GE – Honeywell merger is the first time the EC has ever vetoed a U.S. only merger, especially one that already had Dept. of Justice go ahead. The BBC phrased the outcome as “effectively reversing an American decision”. So why does the EC even have jurisdiction if both companies are U.S. based, and how could it come to the opposite conclusion as the U.S. regulators? European Commission Review: The European Commission on Competition has jurisdiction to review mergers that have a “European dimension.” As major firms, both Honeywell and GE have substantial business assets and activities in Europe. It should also be noted that GE alone employs over 85,000 people in Europe and had $25 billion in revenues from Europe in 2 2000. This unspoken code of conduct, where the EC can review an exclusively American firm merger, is part of the long running system of cooperation between the antitrust authorities in America and Europe. Usually, the two regulatory bodies reach the same decision, even if they don’t use the same analysis to do so. Even when they do disagree, so far they have always found a middle ground, a set of changes to the proposed merger which would make it acceptable to both parties. The 1997 review of the Boeing and McDonnell Douglas deal was one just like that where the initial findings left America in support of the merger and the EC planning to block it. In the end, after substantial political intervention by then President Clinton, the merger proposal was reconfigured in a way both the EC and the DOJ could support. A major impetus for the stage two investigation which was undertaken in early 2001 in the GE – Honeywell merger was the complaints of competitors. In addition, the Commission seemed to take its own hard line on the merger under the direction of Commissioner Mario Monti. There was a 155 page report issued by the Commission on the merger put out on May 8th 2001, followed by a two day hearing that started on May 29th. Unlike the American system, in the EC the people who investigate and collect data on a merger are also the ones to pass judgment on it. GE claimed they were ambushed by having only two weeks to prepare for the hearing after receiving the Commission’s objections when the competition and others against the deal had been working with the Commission for over six months. The Commission’s review was heavily criticized and the investigation and judgment was conducted under extreme pressure from journalists, lobbyists and Wall Street arbitragers who were berating the Commission and major players with calls throughout the process. When Jack Welch learned the Commission was viewing the proposed synergies of the merger unfavorably, he personally called Andrew Card, the chief of staff to President Bush, who happened to be meeting with European leaders that week. While Bush never openly conversed with the EU government on the issue, he did make statements to the press on June 15th about his concern over a European rejection of the merger. Monti seemed personally insulted by the attempt to involve politics in the Commission’s decision. Mr. Monti denied that European protectionism was a motivating factor in the decision but U.S. politicians and pundits jumped on the story, framing it as the EC picking on two U.S. companies in an effort to unfairly favor competitors of GE. There was a threat of retaliatory action by U.S. politicians, though none ever came to pass. Senator Phil Gramm, ranking member of the Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, stated his concern that bad policies will be imposed on the United States through European protectionism. Other Senators warned of “a ‘chilling effect’ on trade relations and possible retaliation from Washington.” During the trial GE managed to end the Commissioner’s case on “bundling” however the Commission held strong to their concern over the vertical integration aspects of the merger. The EC was mostly concerned with the integration of Honeywell’s avionics and GE’s jet engine strength leading to a dominance of the market. The fear of 3 the EC was that the strength of the merged companies would foreclose market competitors in the European markets for jet equipment. When you consider the market that would be impacted by the merger, the major airlines who purchase the engines and avionics sold by GE and Honeywell stand out. Members of this market did think a merger between GE and Honeywell could impact its competitiveness, 15 airlines lodged concerns about the merger to the Commission, though most remained anonymous and only Lufthansa attended the tiral. Mr. Monti was clear that he was not acting solely in the interest of the market for airplanes, represented by the major airlines, but that his decision also sought to protect the interest of the two major competitors to GE in the aircraft-equipment market (United and Rolls Royce). The EC appeared, at least outwardly, willing to negotiate with GE in order to craft a merger deal that would be acceptable to the Commission. The EC asked for some very large changes is GE structure, asking that GE sell off almost 20% of its GEAC division, specifically asking them to sell off those parts to an industry rival. When GE put the offer to sell 19.9% of GEACS on the table it seemed to be too little too late for negotiations with the EC. Some critics claim the EC never intended to allow the GE-Honeywell merger to go through, even with a reconfiguration of the concerning areas of the two companies. The changes the Commission wanted undercut the very aspects of the merger which made it attractive to GE, the synergies between the avionics technology and the jet engines. Honeywell, in a last ditch effort to keep GE interested, reduced its cost by $1.8 billion (saying that would compensate for the forced sale of 19.9% of GEACS). Even with these half hearted attempts to keep the deal going, it was quite clear by July 3rd 2001 that no deal was going to go through. GE did not actually withdraw its offer of a merger to Honeywell, because that could make it liable to a Honeywell lawsuit. Some in the press thought GE backed off of pursuing the deal at full steam because they had second thoughts about the health of Honeywell, as more and more information was made available during the investigation and the market reacted to Honeywell’s prospects. The official kibosh on the merger from the EC came nine months after the initial proposal of the merger. How could GE fail a review by the EC which it flew through with American regulators? The only possible explanation is that American and European regulators are asking different questions and requiring different things of potential mergers. Differences in E.U. and U.S. Review: Since most of the time American and European antitrust regulators reach the same conclusions, the nuanced differences in the review process of the two groups is not well known to those American firms who must also seek EC approval of a merger. The GE – Honeywell merger showed American companies that what you don’t know about the EC review process can hurt you. For starters, which proposed mergers actually come under review by regulators in America and Europe is vastly different. In the U.S., any merger with one party having 4 over $100 million in sales or assets and the other having over $10 million gets reviewed. In the E.U. the assets or sales of the company has to be at least $2.5 billion to be reviewed by the Commission on Competition, almost 25 times larger. This does not mean mergers are easier in the E.U. however, because smaller deals have to be reviewed by the competition authorities in each affected E.U. member state. Still, the BBC points to increasing anecdotal evidence that the EC is ‘tougher’ on mergers than the antitrust agencies in the U.S. when it comes to mega mergers, such as one between GE and Honeywell. Other than which mergers are reviewed, the method of analysis is also different in several critical respects. The E.U. and the U.S. seem to have different definitions of what ‘market’ is being affected by the merger. Mr. Monti pointed to the idea that the implications for the GE - Honeywell merger would be different for Europe than they would be for the U.S. and that those differences explain the difference in regulatory treatment. While the market of customers and competitors in an industry like jet engines is likely global in scope, there is the potential that variations in markets between the U.S. and the E.U. could account for the different outcome. The U.S. aviation market is nothing if not complex and some of those regulatory complexities could create different outcomes for a change in market power than they would in Europe. Variations in markets are not the only difference. CNET points out that another variation is who the regulatory agencies think they are supposed to be protecting. The EC seems to focus more on the effects of a proposed merger on the competition whereas American authorities are focused on the effects mergers have on customers. Experts are not of one mind on the issue. An Emory Business School professor, Rajendra K. Srivastava found it suspicious that Monti changed his arguments against the merger over time, first focusing on the “bundling” and when that was put to rest, taking up the “harm to competitors” banner, and later shifting the focus to the GEAC impact on the market. Srivastava seems to sympathize with GE because the EC was giving them an unbeatable “moving target”. Edward T. Swaine of the Wharton School of Business on the other hand, finds claims of anti-Americanism, or that the Commission focused too much on the impact on competitors were overstated and likely did not impact the decision (though Swain still thinks the ultimate decision reached was wrong). BBC commentators have highlighted that the E.U. and U.S. authorities also differ in how they approach a market power analysis. The E.U. is tougher on portfolio power, such as where cross- selling products is seen as being damaging to competition. This emphasis is a direct result of their focus on the effect on competitors as opposed to the U.S. focus on consumers. The EC also looked at long term anticompetitive effects, which by their nature are less predictable than the typical analysis of short term effect on the market. Some in the American antirust analysis even thought the GE-Honeywell merger would increase competition in the short term. The European analysis on the other hand saw less firms in the industry as bad in the long run, regardless of the actual economic outcome. Even though the variations are nuanced, with different analysis being done by American and European regulators it is actually surprising the GE – Honeywell merger 5 was the first to be decided on differently by the two regulators. Still, the decision by the EC to block the GE- Honeywell deal was a shock to many, GE first among them. The fallout from the failed merger was devastating for Honeywell and debatably good luck for GE, but the fallout extends to all American companies who are now on notice that U.S. approval will not be sufficient. The EC has successfully staked its claim as a power player in exclusively U.S. company mergers if they impact Europe. Fallout from the Failed Merger: In the end the failed deal hurt Honeywell the most, according to Swaine of Wharton. The large amount of time for the resolution of the deal put Honeywell in a position to lose talented people and caused long term projects and strategies to be put on hold. This is one of the long term costs of any merger, but it was made exponentially more difficult by having to go through both the U.S. and E.U. regulatory systems. Russell Coff of Emory says that this is just something companies are simply going to have to get used to because the idea that companies like GE are “U.S. firms” is dated in this global economy. The outcome for Michael Bonsignore, Honeywell’s chairman, was bleak. In fact, he resigned because of the failure of the merger. Honeywell also saw negative financial implications from the disintegration of the merger. Annual profits were down 92% in April of 2001 and they had to cut 6,500 jobs. Jack Welch, GE’s chairman, ended his career on a low note instead of a major triumph, he had postponed his retirement to see the deal to completion. Honeywell could have sued GE under the theory GE did not use the “best efforts” to get approval of the deal by the required regulators. The merger deal had a clause that required GE to use best efforts because otherwise companies could get out of deals through technicalities with regulators and avoid paying the costly financial penalties for breaking off a deal. The LA Times reported that the breakup fee in the GE – Honeywell merger agreement was $1.35 billion, far more than a simple inconvenience. Commentators knew such a suit from Honeywell was unlikely even right after the decision, GE did try and no one would expect them to undermine the central elements of the deal that made the merger profitable simply to make a point to the EC. The Economist and other news reporters on the failed deal point out that the Commission’s finding that GE has a “dominant position” in some of the markets for airplanes in Europe could pose future problems for GE. Even after losing the case with the Commission, GE had reason to take the appeal to the E.U. Court of First Instance in Luxembourg. While it couldn’t save the Honeywell merger, it would allow GE to fight the precedential finding that it has a “dominant position” in the airplane market that it is likely to abuse. The appeal to the Court of First Instance (CFI) took more than four years, with an affirmation of the Commissions decision coming out in December of 2005. GE was unable to overturn the holding that it held a dominant position in the market for certain jet engines however the Commission did not come out looking all that great. The CFI determined that the Commission failed to prove a case against GE for bundling, and also 6 questioned the logic behind the GEACS reconfiguring. In the end the Commission’s veto of the merger was upheld on the basis of the Commissions case on “market share, of the reinforcing effect of GE’s vertical integration, and of the state of competition on the market.” Not all the opponents to the GE - Honeywell merger are actually happy with the Commission’s decision. Many of them simply wanted the deal weakened, and competitors wanted the opportunity to buy up portions of GE’s business it would sell off in order to force a deal through. They were as unhappy with the full blown killing of the deal as GE and Honeywell. In the end, Swaine sees the GE Honeywell failure as a “cautionary tale” for all multinationals “about the need to seek specialized (legal) advice as early in the process as possible” in order to pass both American and European obstacles to mergers. While Monti was upset by the attempt to involve politicking in his economic decision, by the end of the process he “could not have been more conciliatory." With an eye to the continued work to be done together with the two regulators, he explained that it was not a matter of "one right decision and one wrong decision" but rather "a divergence." The U.S. response was less genial, the head of the DOJ antitrust division made a statement on the same day as Monti saying “[c]lear and longstanding U.S. antitrust policy holds that the antitrust laws protect competition, not competitors." There were likely several awkward days at the office for those two groups. This is not the end of cross-Atlantic review of “internal” mergers. According to TIME, the E.U. Commission on Competition is reviewing three separate investigations of Microsoft. On the U.S. side, American regulators investigated the purchase of Ralston Purina by Nestle, both European companies, as that deal would consolidate over 50% of the $3 billion cat food market in the U.S.. The role of the CFI in overturning several Commission decisions because of faulty logic or analysis has led to some changes in the Commissions analysis, but there are still major differences in American and European antitrust policy. The CFI affirmation of the Commission’s veto of the GE- Honeywell merger shows there are still areas of disagreement and no clear method for dispute resolution when the regulatory authorities come to differing conclusions. Going Forward: After the 1997 disagreement between the E.U. and the U.S. on the acceptability of the merger between Boeing and McDonnell Douglas, which eventually required direct intervention by President Clinton, who had to threaten trade sanctions from the WTO to get the reluctant approval of the EC, it was already clear that a better system for how disagreement should be handled needed to be developed. Now that the two have actually come to divergent final determinations, a process for dispute resolution and a way to make clear to multi-national firms what is expected of them is desperately needed. The old system where they “strive to coordinate their work as closely as is considered appropriate and practicable” is clearly not going to solve every issue. The day after the official blocking of the merger by the EC, Commissioner Monti himself called 7 for the creation of an annual global competition forum where regulators can meet to share experiences and work to create synergistic policies. Some commentators think that an “international competition code superimposed on national laws and applied by a single global competition authority” is the way to fix the problem, others want to send the issue to the WTO. Monti, a reasonably strong authority on the issue, says he would not support any global attempt at competition law if it would require any changes to national laws. Others say just let the system go on as it has, the incidence of conflicting findings has been low enough in the past that a “take it as it comes approach” wouldn’t be too strange a policy. The overall number of mergers which were reported to the European Commission is now between 200 and 300 per year, whereas it was as low as 60 per year in 1990. With such an increase in volume, although the GE - Honeywell clash was the first between U.S. and E.U. regulators, it will likely not be the last. The Commission’s decision to block the GE-Honeywell merger has served an important purpose, all American firms are now on notice that the European Commission on Competition is not simply a figurehead, and that they will not blindly follow American regulatory decision. Merger specialists and legal counsel for firms considering mergers which would come under the jurisdiction of the EC now have more work to do. They must consider any differences in the European market for their products and must look at the merger through both the pro-consumer lens of American regulators and the pro-competitors lens of European review. As more and more industries become global in scope, the idea of a purely internal American firm merger is falling by the wayside. The European Commission on Competition cannot be ignored, and as other areas of the world such as Asia-Pacific become more and more organized, other regulatory schemes may have to be complied with down the line. The differences in analysis by an Asian competition authority could be much more drastic than the variations between American and European analysis. As the potential for conflict continues to rise, a global system either of review or at least of dispute resolution could serve a very important purpose. Such as system, either under the auspices of the WTO or in some other form should continue to be advocated for, if for no other reason than the sanity of merger specialists and legal counsel for major global corporations. 8