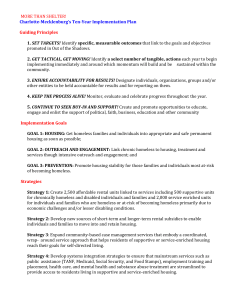

Evaluation of Continuums of Care For Homeless People Final Report

advertisement