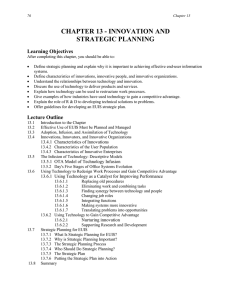

Chapter 13 Innovation and Strategic Planning

advertisement