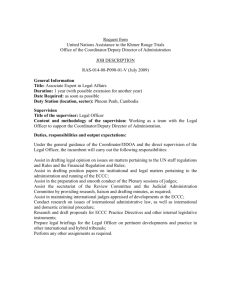

The Future of Cases 003/004 at the of Cambodia

advertisement