“M Let’s do more with less David A Buchanan

advertisement

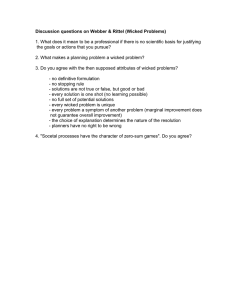

FEATURE Let’s do more with less David A Buchanan and Steve Macaulay discuss developing middle managers for the front line of change “M anagers are the jam in the sandwich. They don’t like the negative stereotype. Even on Holby City the manager is the bad guy, the lowest of the low. The NHS itself is not doing anything to curb ill feeling towards management.” (Operations manager) Middle managers often have a poor reputation. Nowhere is this truer than in the health service: UK healthcare managers attract a lot of criticism, and have been described as unnecessary ‘grey suits’ and costly ‘pen pushers’ by government ministers. However, the findings from our recent study involving 1,200 middle managers in the NHS paint a radically different picture. Who are these middle managers, what contributions do they make, what gets in their way and what key capabilities do they need? The reality is that middle managers are on the front line of driving change. This is not widely recognised, however, and they are poorly supported in this role. This article describes the key role that middle managers play, and how L&D can spearhead supporting investment that could generate significant returns, for little cost. The NHS is one of the largest employing organisations on the planet but figures show that only around 3 per cent of its 1.3m staff in England and Wales are ‘managers and senior managers’. However, this calculation excludes middle managers, and does not count those whose ‘hybrid’ roles combine clinical and managerial responsibilities – ward sisters, matrons, laboratory supervisors, clinical directors and so on. Around 30 per cent of the staff of a typical acute hospital have managerial roles, when those other managers and hybrids are taken into account. It is often said that ‘clinical staff are not engaged in healthcare management’. That is not true. In that typical hospital, the hybrids outnumber the pure managers by four to one. National policy has created a massive change agenda for hospitals, which are required ‘to do more with less’, to reduce their costs, while improving the quality and safety of care, at a time when demand for acute services is rising along with patient expectations of quality of care. The capacity for driving these changes thus sits mainly with a hybrid group, many of In search of middle managers “ You’ll hear people say ‘management’ in inverted commas. And I’ll say ‘but you all manage’. I think that there’s always been quite a hierarchy in the NHS and we need to break that down. I want everyone to take accountability and responsibility.” (Modern matron) 29-33 TJ.indd 29 24/06/2013 12:37:26 FEATURE whom have little or no management training, work only part time as managers and do not even see themselves as managers. National policy involves reducing the numbers of (pure) managers in the health service. This will only place a greater management burden on hybrids who are already stretched to cover both clinical and managerial responsibilities. How do middle managers contribute? “Managers make a huge contribution to patient care, developing services, measuring quality. I go to all the clinical meetings and I act as a lynchpin. If I’m not there, the discussion and outcomes can become fragmented.” (General manager) Despite the many challenges, middle managers make major contributions in the following areas: • maintaining day-to-day operations, keeping the show on the road • firefighting and troubleshooting, performance management, solving ‘wicked problems’ • championing innovation and change, spotting and designing service improvements • performance improvement, leveraging targets, dashboards, benchmarking 30 29-33 TJ.indd 30 • developing infrastructure, IT, equipment, physical facilities • managing serious incidents, implementing remedial actions • developing others, staff development, teamwork • managing external partnerships and relationships, across the wider community • patient experience focus, ensuring business decisions consider the patient’s voice. Middle managers are thus on the front line of operational management and change implementation, contributing to improving the quality of the service as well as organisational effectiveness. If the distinction between management and leadership is that managers ensure smooth running while leaders drive change, middle managers are clearly both, and they are primarily leaders. This profile is a long way from the stereotype of the expensive change-resistant bureaucrat. But most of the managers to whom we spoke felt that they were simply under so much pressure that they didn’t have time to develop those contributions as fully as they would have wished. So what can be done? July 2013 www.trainingjournal.com 24/06/2013 12:37:29 properties in practice top team communications clear, consistent, two-way, listening business intelligence IT systems that provide appropriate and timely information, easily zero non-value-adding streamlined governance, simplified audit and compliance systems autonomy to innovate fixing problems on own initiative without sign-off delays organisation structures no silos, information sharing, cross-service collaboration organisational norms patients not targets, engagement, management valued, risk taking performance management hold managers to account, provide support for performance problems inter-professional work mutual respect between clinical and managerial staff support services rapid, appropriate advice, action, and problem solving personal development leadership and management training and development teamwork collaboration, information sharing, consider wider impact of decisions resources staffing, investing to save, granting decision rights within budget Making an even bigger contribution “Implementing anything new takes massive amounts of energy, and you are ground down, with doors closed in your face repeatedly. It’s hamsters on the wheel.” (Modern matron) It comes as no surprise that, in the current economic climate, the single main challenge for hospital managers is the pressure to cut costs. But this is not the only factor affecting their output. Most are faced with increasing workloads, and note the lack of ‘head space’ and the need for ‘broad shoulders and thick skin’. Then there is the daily pressure to meet exacting performance targets and to deal with burdensome regulation. IT systems in many hospitals are dated, are difficult to operate and maintain, and provide inadequate information, which is often late. While there is no shortage of ideas for service improvement, there is often no money to implement changes. Constant staff shortages, recruitment problems and increased job insecurity are other headaches. Many middle management roles have become ‘extreme jobs’: long hours, fast pace, high intensity and pressure, uncertainty, rapidly changing priorities. We found many middle managers who enjoy the pace, excitement and challenge but multi-tasking across complex roles can lead to fatigue, burnout and mistakes that, for hybrids, may have adverse consequences for quality of care and patient safety. Practical steps to create an enabling environment We asked managers what practical steps their organisations could take to give them the headroom, to allow them to make even bigger contributions to clinical and organisational outcomes. The table above summarises their suggestions describing what it takes to create an ‘enabling environment’ in which managers could make even stronger contributions. “I’ve been inspected recently by six different agencies. And they all want information, reports, and action plans. Nobody ever asks me how many lives we’ve saved, or how many people got better as a result of the treatment they received. I spend a lot of my time writing policies.” (Emergency department lead nurse) The actions necessary to building and maintaining such an enabling environment are relatively simple, and they are also cost-neutral. Middle managers need more space, more time, more autonomy. Simplifying organisation structures, streamlining governance, reducing bureaucracy, giving people more freedom, more discretion, the ability to innovate, to take risks, to introduce changes – you can do all of this for free. The L&D agenda: key management capabilities “We don’t have any managerial training and lots of work is left to us. I expect that in the future we will be left to make more decisions.” (Ward sister) Many middle management roles have become ‘extreme jobs’ www.trainingjournal.com 29-33 TJ.indd 31 July 2013 31 24/06/2013 12:37:30 FEATURE Managers need to strengthen their capabilities. The national austerity that is reducing public expenditure seems likely to continue for several more years. The health service will continue to be affected, despite rising public expectations and increasing demand. So, what capabilities do middle managers need in this high-pressure, rapid-change context? A modern matron answered that question defensively, saying: “Look, I think I have the capabilities to do my job. I’m just not allowed to use them.” That is a telling remark, which would be shared widely across the middle managers involved in this study. However, many hybrid managers do not have a management background. They may have been on a short course for a couple of days, but few have any substantial management training. Our study suggested that a small number of key capabilities carry a premium in the current context: • political skill All managers have to be able to negotiate the internal politics of a ‘professional bureaucracy’, in which different interest groups share power but do not always share the same perspectives and goals, thus making political skills essential • resilience ‘Mental toughness’ is needed to deal with painfully slow bureaucracy and change, setbacks to established plans, and recurring challenges concerning failures to meet performance targets; in terms of building resilience in challenging settings, healthcare could learn from military experience • inter-professional collaboration Some of the most powerful changes we saw implemented during our study were based on close clinicalmanagerial partnerships, which are increasingly critical but can be difficult to establish because they require mutual trust and respect, and abandoning traditional stereotypes • performance management Managers openly admit that the service does not handle poor performers well; a common sentiment is ‘we’re too nice to each other’. Poorly performing staff are often moved on to another area, and this dimension of human resource management has to change • financial skills It is difficult to reduce spending and increase efficiency when you don’t have accurate and timely information about your cost drivers, where revenue is being generated and which services are loss-making. The NHS funding model is increasingly complex, and a wider understanding of how it works would be invaluable 32 29-33 TJ.indd 32 July 2013 www.trainingjournal.com 24/06/2013 12:37:32 • addressing wicked problems ‘Tame’ problems are clearly defined and you know when you have solved them but most management problems are ‘wicked’, with different stakeholders having competing views on the nature of the problem and how to solve it. There are no ‘right or wrong’ solutions, only better or worse ones. What does this mean for L&D? L&D can do much to close the gaps in skills and knowledge. Here are two examples. Political skill: During the research, we were asked to run (separate) development programmes in organisational politics for senior nurses, operations managers, and foundation trust governors at one hospital. These sessions included a diagnostic, ‘how political is your organisation’, identified common and rare political tactics, assessed the individual and corporate costs and benefits of ‘playing politics’, explored with real cases how the constructive use of organisational politics can enhance reputation and performance, and ended with a self-assessment of participants’ political styles. Wicked (ill-defined) problems: We were also asked by another hospital to run workshops on wicked problem solving for their ‘100 leaders’ cohort. In addition to exploring the differences between tame, wicked and ‘super wicked’ problems, these workshops introduced participants to the tools of end-state mapping (what do we want to achieve?), mess mapping (visually representing the problem) and multi-level future mapping (necessary actions). These tools are less important than the productive dialogue that they encourage, typically (as in this case) involving stakeholders with wildly differing views of the problem and how to solve it. The ‘wicked problem’ that they chose as the basis for this discussion was why are we not managing poor performance effectively? Could this apply to your organisation? “We want to turn this into a great organisation, a great place to work. We need to engage people or lose talent, especially in general management roles. Retaining talent in management roles is going to be a problem. They could just walk away to other sectors.” (Director of human resources) The health service could usefully capitalise on managers’ motivation and commitment by promoting a positive image of their contributions to patient care, and by empowering them to solve problems and to drive innovation and changes on their own initiative. We need to move beyond the traditional negative stereotypes of middle The reality is that middle managers are on the front line of driving change management, and to recognise and develop their key strategic roles in designing and implementing change and innovation. This conclusion is consistent with research in other sectors, where middle managers are seen not just as passively implementing senior management directives but as acting as intermediaries between frontline and top team, helping to shape and drive service developments and future strategic directions. There is a tendency to see the NHS as isolated and uniquely apart from other organisations. We would simply pose these questions: • do these conclusions and recommendations apply to your organisation, whatever the sector? • do you have a middle management group that makes unrecognised, unrewarded and underdeveloped contributions to your business? • are they central to shaping the mission-critical changes that you know are going to be necessary? It is time to take a fresh look at these ‘leaders in the middle’ and the context in which they operate, and to consider the business impact of increasing the levels of recognition and support that they receive. Remember, increasing recognition and support may not cost you anything but could unleash fresh ideas and the energy and space to implement them. The research on which this article is based was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme (award number SDO/08/1808/238 How do they manage? A study of the realities of middle and front line management work in healthcare). This article is based on independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in it are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health. www.trainingjournal.com 29-33 TJ.indd 33 David Buchanan is professor of organisational behaviour at Cranfield School of Management and co-author of Power, Politics and Organisational Change. He can be contacted at david. buchanan@ cranfield.ac.uk Steve Macaulay is a learning development executive at Cranfield School of Management. He can be contacted at s.macaulay@ cranfield.ac.uk July 2013 33 24/06/2013 12:37:34