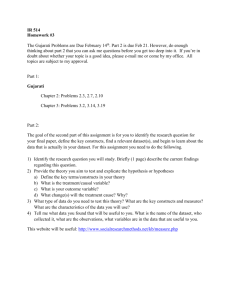

The Nature of Accounting Information Reliability:

advertisement