M EADOW the

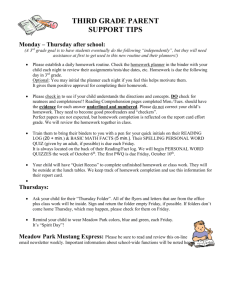

advertisement