UACES 45 Annual Conference Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015

advertisement

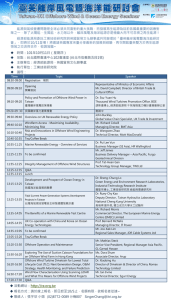

UACES 45th Annual Conference Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 Conference papers are works-in-progress - they should not be cited without the author's permission. The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s). www.uaces.org FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 1 UACES Conference, Bilbao, 7-9th September 2015 Session 8, Panel 804, Wednesday 9th September, 0930-1100hrs DRAFT ONLY-PLEASE DO NOT QUOTE OR CITE WITHOUT AUTHOR'S EXPRESS PERMISSION! "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." Illustrating the predominantly local and national nature of offshore wind politics; In 2012, locals in Aberdeen, Scotland were mobilised into pro and anti-offshore wind-farm activists, while Donald Trump, owner of nearby Gold Resort weighed in to denounce offshore wind plans. As on June 2015 the project secured full planning permission and survived all legal challenges in the Scottish Courts. Picture credit: http://www.thecommentator.com/article/3250/the_donald_seeks_to_trump_scottish_government_over_wind_farm_dispute Dr. Brendan Flynn Árus Moyola, School of Political Science & Sociology, National University of Ireland, Galway. Galway City, Ireland. E: brendan.flynn@nuigalway.ie T: 00 353 1 493160 Your comments and feedback are welcome at email above FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 2 Abstract This paper critically examines the role of the EU as regards marine renewables. These technologies are important within the wider European turn towards renewables, especially for a few countries that have heavily invested in such devices, notably Germany, Denmark, Belgium and above all, the UK. The paper asks whether we should expect much from a promised EU energy union or whether a retreat from ambition in EU renewables policy threatens to undermine the growing marine renewables sector. The core argument offered here is that the most important locus for key decision-making on marine renewables remains the national level. In large part this is because the details of fiscal incentives continue to be mostly decided under national budget rules, while the favourability of local planning laws remains an issue which the EU only shapes in broad terms, not in detail. Accordingly, the making and breaking of marine renewables is more a story of national politics, replete with national heroes and villains. The most recent data on offshore wind is presented to show that the UK is the clear pioneer states for marine renewables, whereas Germany's role as a leader on offshore renewables is revealed to be more modest. The British experience of offshore wind is recounted with a focus on detailing the importance of the national context. Introduction: Renewables in era of Energy (dis)Union? If Europe's experiment with monetary union has proven so flawed why should we expect an Energy Union to fare any better? This neatly sums up the political problem that the Europe Union must face in constructing a cohesive energy policy for very diverse member states. While there has always been controversy over the role of the EU versus national governments in given policies, what is also in question today is whether EU leadership would be credible. The output legitimacy of the EU, the ability to deliver effective policy leadership, is now as much in doubt as any well-known weaknesses in input legitimacy (voice, votes), to use the language of Fritz Scharpf (1999, pp.7-28). Moreover, encouraging renewable energies is only one EU policy goal alongside a slew of other energy issues. To be blunt when it comes to energy the EU remains focused on removing national barriers to energy flows and the creation of EU wide energy markets which have formed the major part of regulatory efforts since the so called Third 'liberalisation' package of 2009. It can be argued that all other goals, such as promoting renewables, are secondary. The EU Commission has recently seized upon the idea of an Energy Union, which apparently means increasing the powers of EU energy regulatory structures and a greater focus on EU leadership on energy security, specifically in the natural gas market where bilateral deals with Russia are common (Giuli, 2015). It is probably not at all unrelated that the EU Commission has called for an Energy Union at the same time that FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 3 monetary union is in profound crisis. Logically this seems puzzling, politically it make sense to the Commission no doubt to keep momentum and importance vested in Brussels. Yet what does rhetoric about an Energy Union mean for the governance of renewables? It is the argument of this paper that we should be skeptical that it will mean enhanced EU leadership or ambition on renewables. After all, without any Energy Union, renewables have gone mainstream in Europe and a green revolution of sorts has unquestionably occurred, at least as regards electricity generation. The extent to which the European Union has been the architect of this transition remains open to debate. Nobody could seriously doubt the importance of the EU's role in helping the rise of renewables across Europe. The question is surely not a categorical one: whether the EU has or hasn't been a driver for Europe's renewables renaissance. Instead it is a matter of interpretation and degree; has the EU's role been decisive in pushing weak national leadership, or conversely, has the EU's role been more modest, brokering the varied ambitions between leader and laggard states over renewables? Moreover, questions of timing come into play. The effect of binding legal targets for 2020 with the RES Directive of 2009 is frequently cited as game-changer which the EU brokered (Wyns, et al, 2014, p.20). However, this downplays the longue durée of renewables promotion both at the EU and especially national levels, which reaches back at least to the 1980s and before. Denmark and Germany began their foray into wind technologies, include offshore experiments, well before the EU got serious about renewables. Local and national coalitions for support were also vital in nurturing such technologies out of the 'valley of death' of commercial viability in the 1990s. Happily today most renewable technologies are relatively mature. EU support for R&D spending has certainly played no small part in this, through various funding instruments notably, ALTENER, the FP7 and soon Horizon 2020 initiatives. However, we are now in an era of political contestation over how much renewables energy there should be, where, and of what type? Renewables used to perhaps enjoy the status of a valence issue-nobody much was against them, the question was would they work and could they be afforded. That has changed today, and an emerging oppositional politics is evident which challenges the green FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 4 credentials of renewables alongside their reliability and affordability (Lauber and Jacobsson, 2015, p.7). Critical in respect of the latter concern is who will pay for subsidies required to sustain these, or whether in fact some renewables may no longer require subsidies, for example onshore wind. Subsidies remain mostly nationally determined and sourced, although the extent to which consumers end up paying for these varies between states. Moreover, such national subsidies have been long-standing: Denmark has operated capital grants for wind turbines since 1981 and feed-in-tariffs since 1984. Danish national laws have also profoundly shaped their pattern of wind farm development; local and co-operative ownerships is still heavily promoted and this has helped to reduce opposition and build social support for the technology. German policies on wind have also been quite particular, with for example a focus on promoting small-scale developers through FITs that emerged as early as 1990. Despite opposition from German utilities, German legislators agreed rules that basically imposed renewables on these 'grid incumbents' at a level way beyond what they considered prudent. Indeed German utilities in the early 1990s saw the EU as a possible venue to overturn the German drive towards renewables, a strategy that failed. Britain by way of contrast adopted quite different subsidy mechanisms with the result that their wind industry is more concentrated as regards ownership. One can quickly see here that national level policy-measures have been absolutely central in steering the style in which renewables are adopted, or indeed what type of renewables are adopted and where. EU rules or leadership over renewables has simply mattered less over such crucial details, although the EU's policy on renewables surely confirmed and supported the national exploratory push towards renewables by pioneer states like Denmark and Germany. So much for history! Today the backlash against renewable energies is also more evident at the local and national level, manifesting itself sometimes through protest and litigation. By way of contrast in Brussels opposition towards renewables tends to come from rival lobbying efforts of legacy energy sectors (gas, oil, coal, nuclear etc). Given that the EU's Treaties as they have evolved, continue to insist that the choice of energy mix is a competence that resides clearly with the member states (Article 194.3), it is not obvious how the EU can steer a path of policy leadership on the question of what renewables should FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 5 be adopted as part of the overall mix of energy sources Europe needs. Yet the EU has certainly promoted specific energy technologies: it was after all founded around coal, steel and nuclear energy. The promotion of nuclear energy continues apace at the EU level, enjoying generous levels of common funding, notwithstanding that the technology is bitterly divisive between and within EU states. Crucially, decisions to build or phase out nuclear capacity remain national, even if electricity traded under single market rules between member states combines different generation mixes, including from nuclear sources. Notwithstanding such details, questions of what type of renewables should be funded and where they should be located seems more obviously ones to be decided at national levels. In some cases this has been worked out bi-laterally for example with joint Swedish-Norwegian renewables obligation certificates. However, subsidies and payments for renewables invoke issues of single market regulation and fair competition. Here the capacity for decisive EU regulation is much greater. Nonetheless, there has been a fundamental ambiguity about how much scope and political acceptance there is for EU leadership more generally. For example in their review of EU policy on renewables, Hildingsson (et al, 2012) make a number of vital insights: "the main driver for RES policy coordination has been internal market concerns, and not the concern about an impending climate catastrophe..(and ). an underlying choice has gradually been made to develop RES [Renewable Electricity Support] policy at the EU level... while harmonisation of support mechanisms is regarded a long-term objective, the Commission have found it too early, given factual variations in resource availability and institutional capacity among states... However, that [further harmonisation] remains to be seen; after all the resistance to a harmonised policy regime seems stronger than ever... it is doubtful whether the Member States and their citizens are yet prepared to accept further efforts in that direction towards deeper integration of energy policy." (Hildingsson (et al., 2012, pp.18, 24-25, 28) Benson and Russell (2015) in their detailed empirical survey of EU energy laws, although broadly optimistic about the growth of EU energy policy leadership, are also equally careful to hedge their bets. "While past evolution is not necessarily a good guide to what may happen over the coming years, we could forward two scenarios premised on this evidence. On one hand, on the basis of past expansion, energy policy could well undergo limited rapid growth interspersed by periods of more incremental expansion. In this case, the adoption of a FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 6 common policy approach and a legal title for energy might, in theory, precipitate greater volumes of EU policy-making in the future. Current and planned policy proposals in response to concerns about energy security and climate change would tend to underline this assumption as a common climate–energy policy slowly emerges... On the other hand, policy outputs may well be less pronounced than this analysis suggests. Drawing on the example of past trends, the ongoing Europeanisation of energy policy could well be resisted by governments if it strays too far into national prerogatives" (Benson and Russell, 2015, p.200). Certainly desires by the Commission to increase their authority over renewables have been obvious at times but these have also been resisted. When drafting the EU Renewables Directive of 2009, the Commission seriously hoped for an EU wide financial scheme of tradable renewable certificates (Knudsen, 2012, p.54, Jacobsson, et al., 2009). Yet this was ditched in the face of intense nation state objections and inconvenient evidence that suggested Feed-in-Tariffs (FITs) were a more effective way to subsidize renewables. The latter was impossible anyhow on an EU wide basis given EU Treaty injunctions against fiscal instruments unless agreed by unanimity. Today the EU faces an important but very politicized choice on this front: will it continue to allow nation states to heavily subsidize renewables on a national basis? In fact in mid 2014 the Commission's Competition Directorate attempted a major re-write of State Aid rules for environmental purposes which would have had the effect of reducing the ability of states to give preferential treatment to offshore wind, although this was diluted (Flynn, 2016). The EU actors are divided over the margin of indulgence that national subsidies and schemes for renewables should be accorded. The Commission, although internally factionalised, has probably the most consistent intolerance for such measures. It generally promotes the case for harmonisation. Interestingly the EU Court of Justice by way of contrast has produced decisive verdicts which have had the effect of confirming national competences on renewables. In 2001 the ECJ ruled national feed-in-tariffs were not in violation of the Treaties (Preussen Elektra case) and in 2014 the EUCJ decided that Swedish and Flemish government green certificate schemes that were restricted to renewables producers within their own territory only, were not violations of the Treaties because such measures were proportionate to the goals of the 2009 Directive and consistent with providing long term investor certainty (Alands Vindkraft and Essent case, 2014). There is some worry however FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 7 that the EUCJ did not fully clarify whether the relevant provisions that allows this in the EU Renewables Directive of 2009 (Article 3(3)2), are not more widely in conflict with the general principles of free trade in the Treaties (Article 34), which a future court may explore in a less favourable way (Szydło, 2015, p.499). The Council is usually divided on giving the EU greater authority over renewables, with the UK showing historically some openness to any common market based approaches which would allow trading of renewable capacity allowances and associated rents. In general though the Council seems to intrinsically prefer compromises that maximise national flexibility. The European Parliament's position appears simply less coherent. A caucus of prorenewable MEPs square off against others who either side with legacy energy interests (notably a raft of German MEPs who are close to the coal lobby) or those who have no strong convictions on renewables. Much of the academic scholarship on renewables continues to speculate over the scope for further EU leadership on renewables to emerge. Here for example is Kitzing's (et al., 2012) somewhat optimistic characterization that slowly convergence is begetting a harmonisation of sorts: "Europe is currently experiencing certain tendencies towards a ’bottom-up’ convergence of how national policy-makers design RES-E policy supports. While some outliers remain, the policy supports of most countries become more similar in the policy types applied (dominance of feed-in tariffs) and in their scope of implementation (differentiation for installation sizes and ’stacking’ of multiple instruments). These trends in national decisionmaking, which show tendencies of convergence, could make an EU-driven ’top-down’ harmonisation of support either dispensable or at least (depending on the agreement) less controversial." (Kitzing, et al, 2012, p.192) Of course this account privileges convergence of instruments, the evidence for which can be argued, but the more basic policy choices seem to remain very divergent: what types of renewables and where they will be located, as well as how ambitious will investment be for renewables? Indeed this paper argues that such divergence can be readily seen in the case of marine renewables, which only a handful of EU states have explored, but in some cases to high levels of ambition. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 8 There is also confusion over the fact that at one level the internal market legislation that the EU has promoted for years has now created a much more integrated trans-national energy and electricity market, if not exactly a giant single market. Umpfenbach (et al., 2015, p.i) describe this tension well: "This shift to more nationalised energy policies arrives at a time when the internal energy market is increasingly becoming a physical and commercial reality. As more electrons travel though interconnectors and price effects ripple through regionally coupled markets, national decisions on the fuel mix have more and more impacts across borders...The move towards more national flexibility in the implementation of the climate and energy framework is thus at odds with the emerging internal energy market." Instead of a true single market, meso-level regionalisation is a strong feature, for example seen in the Nordpool electricity market. Regionalisation is indeed being touted as one way that future EU renewables targets might be met, by collaboration between groups of nearby states rather than at the level of individual states (De Jong, 2014). There is unquestionably a growing functional pressure from the success of so much intermittent wind and solar sources being added to various national grids. For example the German, Danish or Irish grids now have so much renewables online that for stability they require closer interconnections with the grids of neighbouring states. Very relevant in this context as regards offshore wind, are regional sub-sea electricity interconnectors and even the idea of a North Sea Offshore Grid, where many wind-farms would be connected up with each other at sea and with nearby sub-sea electricity cables to both reduce the intermittency problem and to widen market access for such 'deep green' electricity (Andersen, 2014, De Decker and Woyte, 2013). The North Sea Offshore Grid idea however, confirms the centrality of nation state actors, and that fact that progress on it has been minimal to date, with no working pilot projects, suggests regional co-operation is actually quite difficult to achieve where the goals are ambitious transition type measures aimed at boosting the shares of (offshore) renewables (Flynn, 2015, Flynn, 2016). The existing Renewables Directive of 2009 has always allowed extensive collaboration between member states in meeting their targets, by the expediencies of statistical transfers, joint projects and shared funding instruments, which in practice are all means to buy in FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 9 spare renewables energy capacity located in another member state. Yet the uptake of this appears to be decidedly underwhelming. Umpfenbach (et al, 2015, p.4) point out that: "The instrument for cooperation on renewable energy that in theory would be the most potent one – the cooperation mechanisms under the Renewable Energy Directive – has barely been used to date". Moreover, the latest biannual progress report on countries NREAPs to the Commission also reveals a very patchy picture of meeting renewable targets despite the official gloss that 25 states are on course to meet their targets, and in the words of Commissioner Miguel Arias Cañete "Europe is good at renewables, and....renewables are good for Europe "1. The latest situation as of summer 2015 suggests that the UK, France, the Netherlands, Malta and Luxembourg may all miss their 2020 targets under Directive 2009/28 (Vaughan, 2015). In any event the 2009 Directive does not exactly confer very strong enforcement powers on the Commission for states who fail to meet their targets (Wyns, et al., 2014, p.10-11). Problems in meeting NREAP targets for many states seems to be particularly focused on renewables for transport, with Biofuels and electric vehicles proving problematic, but the more obvious problem has been the global great recession since 2008, which continues to leave many EU states with fragile budgets unable to sustain generous national subsidies. This has undermined Spanish, Portuguese, Greek and Irish renewables subsidy schemes but also those of several East European states as well (Fischer and Gedén, 2013, p. 6). In short, the 'success' of the Renewables Directive of 2009 remains very much a work in progress. Finally, a policy narrative has increasingly taken hold for how we should understand the EU's current position on renewables. Whereas the renewables Directive of 2009 (2009/28/CE) pushed member states to become ambitious about renewables by the expedient of legally mandatory capacity targets for renewables (Knudsen, 2012, Hildingsson, et al, 2012, p.21, Fauconnier, 2015), the latest legislative direction offered by the EU has become watered down, with legally binding targets being ditched in the face reassertions of national sovereignty (Umpfenbach, et al., 2015, p.iv). 1 See: European Commission Press Release, "Renewable Energy Progress Report", http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-15-5180_en.htm FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 10 The EU Council in October 2014 struggled to agree new targets for renewable electricity, but in the end agreed a formula whereby the EU28 are supposed to reach "at least" 27% of final energy consumption by 2030. While this may be a cost effective target, it is not exactly that ambitious (Wyns et al., 2015), especially given that the share of RE in final energy consumption was already 23.5% by 2013, or considering that the European Wind Energy Association (EWEA) had argued for a target of 28.5% by 2030 from wind alone (EWEA, 2013). Unsurprisingly Greenpeace labeled the new EU policy on renewables a 'sellout' (Lynch, 2014). Moreover, the weasel words "at least", indicate some countries will be free to exceed the 27% "target", but more generally the formulation used is that it will be met by the EU collectively (Knorpf, 2015, p. 51, Wyns, et al, 2014). In other words, there will be no binding national targets set by the EU for the member states for RE shares after 2030 although there may indeed be national plans required. The absence of binding national targets has already been signaled out as a cause for concern by the European Wind Energy Association (EWEA) who argued there should be some means by which weak national ambition can be 'engaged with', together with an expansion of EU leadership over the funding of renewables (EWEA, 2014a). Yet as of summer 2015 we await a new RE energy package from the Commission, to be finalised no later than 2017, and which will show how the EU collectively can reach the 27% target. This may reflect a global deal on Climate Change emissions after the Paris COP21 meeting, but it is unclear how ambitious it will be. Of course some member states will probably continue to have binding national targets agreed for the period to 2030 and beyond, but these are national measures agreed as part of domestic political bargains. The implication usually drawn from this current lack of ambition on renewables at the EU level is that an inevitable retreat, a slowdown, or at least damaging period of uncertainty for renewables beckons (Jacobsen, 2014, p.352, Wyns, et al. 2014, pp.13-14). Moreover, this narrative casually assumes that the EU's policy on renewables has in the first place had such a great stimulus effect. The assumption is the EU can more or less make or break renewables, yet is this accurate? Overview: Europe's Marine Renewables Renaissance. While Europe has unquestionably seen a renaissance in renewable energy, a distinctive part FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 11 of this has been associated with marine renewables, chief of which is offshore wind. There are also evolving technologies for wave, tidal current and tidal range sources, as well as more exotic forms of ocean energy or even the possibility of sea based solar devices and seaweed biomass. However, these latter technologies remain very much at development stage and may only become viable by the 2040s-2050s, although the UK already shows signs of leadership on more mature tidal current and wave devices, and there are clusters of innovation in other European states as well (Flynn, 2015). Nonetheless, it is important to stress that to date, Europe's offshore renewables experience has been overwhlemingly about offshore wind. As of June 30th 2015, some 10,393.6MW of installed offshored wind capacity was connected to grids in European waters (EWEA, 2015, p.3). This translates into over 3,000 wind turbines in 82 marine wind farms which are located in 11 countries (Ibid.) Figure 1 below provides a summary of the current cumulative offshore wind capacity, as measured by installed MW, for 11 European states. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 12 FIGURE 1 INSTALLED CUMULATIVE EUROPEAN OFFSHORE WIND CAPACITY 2015 What Figure 1 also shows is that while quite a few countries have some offshore wind capacity, ony a few have really gone for the technology, so it remains clustered in just a few countries. These are notably the UK, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, and the Netherlands and Sweden to some extent. The two clear front runners or 'pioneer' states are rather obviously the UK and Germany. However, cumulative installed capacities do not tell the whole story. First we should note that ambition on offshore wind is not simply explainable by geographical determinism: the European countries with the most favourable wind conditions do not necessarily have the highest installed capacity. For example both Ireland and Norway have very high wind energy potential but their cumulative capacity of offshore wind is puny, and Norway does not bother to even include any targets for offshore wind in her national renewables energy plan2 despite having some capacity installed and local industrial expertise. For now the Norwegian Although not an EU member, Norway and other EFTA states have produced NREAP plans which follow the template of Commission documentation. Moreover Norway participates in a joint renewables tradable certificates scheme with Sweden. 2 FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 13 approach seems to be focused on a pure technology developement approach which is centered on floating wind turbines as the next generation device (Kaldellis and Kapsali, 2013, p.140). Equally there is obvious wind potential for Mediteranean France and Greece which has yet to be exploited, as Figure 2 shows. Yet the geographical dimension to offshore wind energy is stark: it is mostly a North European passion and focused for now largely in the North Sea or Western Atlantic. FIGURE 2 EUROPE'S OFFSHORE WINDRESOURCE Source: http://www.pib.gr/usrimage/wind%20resources%20europe.jpg Given this odd geography, some commentators may dismiss offshore renewables as a niche development of little significance as regards Europe's overall transition towards a much greater share of renewable capacity. By the end of 2014, offshore wind in EU states had FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 14 some 8,000MW installed capacity whereas onshore wind had 128,800MW, which has been deemed equivalent to 10.2% of total EU electricity consumption with the share of offshore wind estimated at close to 1% of EU electricity consumption (EWEA, 2014, p.3). Offshore wind capacity as of 2014 then represents some 6% of the total EU installed wind capacity, indicating that land based wind still remains dominant for most countries. This may seem a tiny share, yet the growth trajectory of offshore wind appears to be very impressive. The UK for example plans for 18,000MW installed by 2020 and possiby 40,000MW by 2030 (Kern, et al, 2014, p.635). The EWEA's own projections are that 40,000MW is possible for 2020 and they even suggest a figure of 150,000MW by 2030, although obviously as a lobby group for wind it is in their interest to 'talk up' projections of what level of capacity is feasible. Yet, Kaldellis and Kapsali in their more cautious academic evaluation of the prospects of offshore wind, suggest Europe's offshore wind capacity will reach 27,000MW within a few years, and possibly as much as 75,000MW could be installed globally by 2020 (2014, p.137). For the countries who have actually embraced offshore wind within their overall national renewables mix, the significance of the sector can also be much greater than the cumulative statistics suggest. This reinforces the argument of this paper that we should consider not just macro trends at the EU level, but examine how specific renewables have been deployed at national levels. Figure 3 below shows the growth of annual offshore capacity (measured in installed MW) for EU states, compared with the the growth in annual capacity for total wind energy over the years 2000-2014. The contrast between the two different types of wind energy is quite stark not least in terms of overall capacity, but the total wind trendline, which is dominanted by land installations, shows several punctuated steps upwards in capacity whereas offshore wind has a slower but steadier trajectory of growth. Also of note is that in the last few years total wind added capacity has stalled somewhat, whereas for offshore wind, the trend is a clear increase. It seems likely that given NREAP plans (see below) whch promise more offshore wind capacity, allied with reductions in subsidies for onshore wind in some member states, we will see the share of offshore new installed capacity rise in the next five years. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 15 FIGURE 3 GROWTH OF ANNUAL EU* OFFSHORE WIND CAPACITY (MW) COMPARED TO TOTAL ANNUAL ADDED WIND CAPACITY 2000-2014** 3 We can also see the relative importance of offshore wind for various countries by examining investment cycles in offshore wind, in effect asking the question what states are consistently investing the most in adding offshore wind capacity. Figure 4 below shows added MW of offshore wind installed capacity for those countries which have been reported in the EWEA annual reports on offshore wind over the five year period for 2010-2014. It should be immediately obvious that only a few states have been active over the last five years, 3 *EU15 become EU28 by the end of this time series;** offshore wind data for first six months 2015 FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 16 reinforcing the point made here that offshore wind is a renewable whose fortunes are tied to domestic decision-making in just a handful of states. FIGURE 4 OFFSHORE WIND ADDED CAPACITY PER ANNUM 2010-2014 AS A PERCENTAGE OF TOTAL ADDED WIND CAPACITY. Once again the pattern that emerges is clear but also very interesting because it modifies the perspective which cumulative installed capacity statistics imply. Just a handful of states have really opted for offshore wind, with the UK, Denmark and Belgium standing out. While Germany has the second highest cumulative offshore windpark after Britain (Figure 1 above), in fact her share of offshore wind capacity investment (7% of total wind capacity added between 2010-2014) is actually very modest. What this data is revealing is that the much vaunted German offshore wind experiment is a lot less revolutionary than it has sometimes been presented, when one considers the share of German offshore wind compared with land based wind. Germany clearly is a leader country for offshore wind when one considers the scale of her offshore wind park, but her ambitions are more conservative in the context FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 17 of overall investment with renewables, and NREAP data (Figure 5 below) confirms this as well. Germany plans a lot of offshore wind but given the overall scale of her onland wind investments she is not planning as large a move offshore as the true pioneers. Here we must single out especially Britain, Denmark or Belgium. They have all been consistently investing in offshore wind to the extent of it representing over 40 per cent of their total new added wind capacity for the the last five years. In the case of Belgium, almost half of their investment in wind capacity over the last five years has been offshore, and yet Belgium is seldom associated as an innovator state for wind as say Denmark. For these three countries,offshore wind has beocme big business and a crucial part of their national renewable strategy. Finally, we can examine the level of ambition of states by noting how much offshore wind, as well as wave, tidal and other ocean energy targets, they have set for 2020. Figure 5 below lists how various countries have included indicative targets, measured by installed capacity in MW, for offshore renewables in their NREAP reports submitted to the European Commission in 2010 and 2011. Table 5 provides a more detailed break down of these indicative objectives. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." FIGURE 5. MEASURES OF AMBITION? 2020 NREAP TARGETS FOR MARINE RENEWABLES 18 FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 19 TABLE 5. BREAKDOWN OF NATIONAL TARGETS FOR WIND, OFFSHORE WIND AND OCEAN ENERGY BY 2020, AS INDICATED IN NREAP REPORTS 2010-11. 2020 Onshore Wind MW 2020 Offshore Wind MW 2020 Tide, Wave, Ocean MW Belgium 2320 2000 0 Denmark 2621 1339 0 Estonia 400 250 0 Finland 1600 900 10 France 19000 6000 380 Germany 35750 10000 0 Greece 7200 300 0 Ireland 4094 555 75 Italy 12000 680 3 Latvia 236 180 0 Malta 14.45 95 0 Netherlands 6000 5178 135 Poland 5600 500 0 Portugal 6800 75 250 Spain 35,000 3000 100 Sweden 4365 182 0 UK 14890 12990 1300 What we quickly discover here is that many more countries have in principle declared an interest in developing marine renewables. Notably France shows up for the first time with a big list of promised installed capacity by 2020, that sits incongrously with her relative absence from the EWEA's data for installed offshore capacities to date. Clearly if France is going to deliver on her NREAP targets she has a lot of cacthing up to do. One could classify France then as a 'latecomer' to offshore wind in particular. Her status as such may not be unique. In many cases the schedule set out in various NREAP documents indicates that investments offshore are due in the final five years to the 2020 target year. This is the case for Malta, Estonia and Poland, whose offshore wind parks are officially promised over the FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 20 next few years. So we should expect to see a lot more offshore wind and perhaps some wave and tidal capacity as well. Alternatively one could compare the actual performance revealed in Figures 1 and 5 with what is promised in the NREAP reports and cite it as a good example of the 'values action gap' in operation for government. The reality is that the NREAP documents are just policy promises by national governments. While it is clear member states are held legally binding for reaching their national target share of electricity consumption from renewables under Article 3 of Directive 2009/28, it is less clear if they can vary the details of their "indicative trajectory" in reaching that target (Woerdman, et al.,2015, p.132, Peeters 2015, Johnston, 2010). Indeed under Article 4(4) of the directive missing indicative trajectories by a small margin may be accepted by the Commission without the need to submit an amended NREAP. It is unclear if the Commission will allow member states to deviate from the indicative capacities for various technologies, wind, solar, etc., as long as the overall national target is met by 2020. Unfortunately, this allows national governments ample room to welch on promises to build and pay for new offshore wind or ocean energy capacities in lieu of capacity from some other renewable. Obviously on the one hand this makes a quite a bit of sense because it gives national governments flexibility. Biofuels for example have turned out to be a much more problematic renewable, and costs have been cited as one reason why offshore wind is not as attractive as it may have looked five years ago. On the other hand, renaging on indicative capacities is very bad planning and there is a well established link between investor confidence in renewables and policy consistency from national governments. Investors want to know that when a states says it wants a certain capacity of offshore wind that it really means it. Given long lead times for offshore developments, it does not look likely that all of the indicative offshore capacity that countries have suggested in their NREAP report we actually be built by 2020. However, Figure 5 does suggest that the pool of countries of who will have a share of offshore wind within their national renewable portfolio will increase, and we can expect some countries to show significant growth, in particular the rise of France as a player in offshore wind and ocean energies is indicated by NREAP plans. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 21 It is the UK however, that stands out as once again the single most distinctive pioneer state for marine renewables in terms NREAP ambitions. In terms of absolute installed offshore wind capacity, Britain plans by 2020 to have more than any other country, even Germany. In relative terms the British are planning for about 47% of their total wind capacity to be offshore by 2020, and the UK is the only EU state that included a very ambitious target for wave and tidal of 1300MW (France's target which is anyhow much less seems to includes their historic La Rance tidal barage station from 1966-which seems like semi-official cheating!). Of course such British ambitions may not come to fruition, and there has been some debate that the releacted Conservative government, now busy cutting subisides for onshore wind, will do little to see such goals realised in preference for fracking and nuclear investments. Nonetheless, the scale and reach of British official planning for marine renewables is truly audacious and places her as a global leader for this sector. Explaining (British) Offshore Wind leadership: the importance of the national? The stand-out position of the UK as a marine renewable pioneer invites speculation about why she has ended up in this position, and for our purposes we might also consider here how important EU push factors were as part of what must be an obviously complex mix of variables, recalling that the argument in this paper is that the national level remains predominantly important in explaining why some states have developed marine renewables and others have not. That position is not one of portraying the EU as irrelevant, but restores a focus upon where academic inquiry should direct the bulk of our research efforts if we want to establish why and how offshore wind will succeed or fail as a transition pathway. In short, it can be argued that the main reasons why the British have chosen to aggressively explore marine renewables lie mostly with domestic political institional settings. EU targets and policies on renewables have unquetsionably played a part of the British story, but arguably a rather small part. Toke for example cites the impending Directve 28/2009 as a 'powerful driver' for changing Britsh government mindsets on renewables to one of ambition, which helped pave the way for offshore wind (2011, p.528) but his account generally stresses domestic factors. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 22 For example, he notes how British interest in offshore wind predated the major push by the EU for binding renewables targets by several years, with one key turning point being a domestic election pledge by the incoming Labour government in 1997 to source 10% of electricity from renewables, and crucially how British energy policy insiders were in agreement that they needed to reduce dependence on natural gas which Britain was now importing after 2005 (Toke, 2011, p.528). The 'dash for gas' which had partly defined British energy policies of the 1990s had by the end of that decade ran out of puff. By 2001 Britain's unique Crown Estate, a commercially managed but public property portfolio holding company, was issuing seabed leases for offshore wind farms. Britain's first offshore wind farm opened 10 years after the very first one in Denmark in 1991. The Crown Estate is of course a uniquely British institution, or crucially national agencies if they decide to become 'true belivers' for a particular technology can become powerful advocates (Kearn, et al, 2014, p.644). Unlike the European Commission, which sees itself as a regulator or civil service, agencies like the Crown Estate are focused on commercial development. While other countries do not have a Crown Estate, they often do have national agencies who have been vital for the promotion of marine renewables. One could cite the Sustainable Energy Agency of Ireland (SEAI), the Danish Energy Agency, and in France, their ADEME (Agency for Environment and Energy) has collaborated with the French Maritime Agency (IFREMAR), to create in a new body, France Energies Marines4, which is a collaborative research and development institute combing significant public and private funding (133m Euro). These sorts of national institutional arrangements have clear ability to improve a country's engagement with marine renewables. Another distinctively national feature emerges here. Under the international law of the Sea, coastal states are granted exclusive economic use of 200 nautical mile zones (and sometimes more depending on geological features, or sometimes less where claims overlap). The seabed is owned by nation states, and that means leases to engage in marine energy activities are firmly a national perogative, unlike say the fishing resources of the EU which 4 See: http://en.france-energies-marines.org/ FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 23 have been 'Communitized' under the Common Fishery Policy. This feature furthers the differences between offshore wind and land based wind development. Because the seabed is state owned, offshore wind inevitably requires greater nation state interest and capacity. Private actors may well build and operate the turbines, but it requires a capable nation states to parcel out access to the sea and seabed. One reason why the Dutch have failed to achieve the high British rates of offshore wind appears to be legal confusion over the exact legislative basis to award leases for developers which was badly managed in the formative years of 2008-2010 (Kern, et al, 2014, p.8). Equally Kern, et al. (2014) are careful to credit Britain's shift from being a laggard on offshore wind to being a leader, as owing some impetus to EU influences. However, in their account, EU renewables targets 'only became helpful to Offshore Wind through actor networks and narratives' (2014, p.642-643), and these were nationally grounded institutional contexts which eventually spawned a dense weave of alliances between core state actors and several other commercial interests. The EU occasionally did force specific details that were significant: for example under State Aid rules British renewables had to be included in the Non-Fossil Fuels Obligation surcharge which was originally meant to fund only British nuclear energy. Subsequently, this provided a funding stream for offshore wind among other renewables. Yet crucially what stands out in the British story is the repeated scale and generousity of national funding. Originally tradable renewable capacity certificates were technology neutral but by 2009, in order to buttress offshore wind developers from rising costs, it was decided to engage in 'banding' which meant offshore wind got more certifcates or in effect became more heavily subsidised (Kearn, et al. 2014, p.643). By way of contrast in the Netherlands, the relevant Minister for Energy more or less abandoned offshore wind energy as too expensive in 2010 (Kern, et al, 2015, p.7). One should also point to the scale and diversity of UK funding instruments which the EU cannot simply compete with. Kaldellis and Kapsali (2013, p.146) describe how various EU funded FP7 projects helped the European industry, but with small amounts of money: a total of €34m. Contrast this with how Higgins and Foley detail a British Offshore Wind Capital Grants Scheme that emerged from the early 2000s worth around £117m, and then how this was replaced with an offshore wind demonstration FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 24 fund worth £30m and an offshore wind business development fund worth £60m (Higgins and Foley, 2014, p.606). What is also important in the British case is to remember that Scotland plays a hugely ambitious role in the UK marine renewable debate (Mcewen and Bomberg, 2014, Allan, et al., 2014). It would be a mistake to understand that Scottish ambitious are simply the engine for all British policy on renewables, yet Scotland probably is the UK's marine renewable pioneer, not least by the accident of geography of resource allocation. However, without the indulgence of the UK's Treasury in London over the last two decades, Britain's offshore renewables revolution would not have occured (Toke, et al., 2013). Moreover, Scottish ambitions for marine renewables are wedded into a UK grid infrastructure which is a necessity for balancing loads and stability, while the UK wide low of expertise and finance is vital. Yet the fact that a devolved government in Edinburgh has been hugely ambitious on marine renewables (Dawley, et al, 2015), seeking to make itself distinctive from UK national policy, has led to a certain degree of policy learning, spillovers, and to some extent innovation by peer competition for leadership over the sector. We are so used to looking for EU-nation state interactions that we tend to ignore push factors that come from below: regional to national policy competition and co-ordination, often co-existing unsteadily. It apears the re-election of the Conservatives in 2015 has cooled the British ardour for offshore wind somewhat. A 'bonfire of renewable subsidies' has occured which means payments for onshore wind will end one year earlier than planned. For now this u-turn has not been directed at offshore capacity (Wintour and Vaughan, 2015). Yet British estimates of offshore wind capacity have been scaled back from 18,000MW to 10,000MW by 2020 and one expert on British renewables has openly worried that "the UK’s offshore wind sector faces a dramatic curtailment once the current round of construction is over and done with" ( Strachan, et al, 2014, Strachan and Broadbent, 2015). If anything, combined with adjustments to local planning laws which will allow English and Welsh local governments more discretion to reject onshore wind developments, the combined effect of the new British government might be to further reinforce the focus on offshore wind in the short term. Moreover, these developments signal that the British debate on offshore wind is now largerly dominated by reducing costs and this is problematic for marine renewables. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 25 If costs do not fall soon, it is possible to imagine a future government in London pairing back investment in offshore wind although the fact that the UK is at risk of missing the EU 2020 target for renewables may act as some buffer from drastic policy u-turns. Fortunately, the offshore wind industry is reporting some very recent signs that costs are indeed falling5. Another issue is whether Britain leaves the EU after the promised referendum on membership, perhaps in the Autumn of 2016. If this happens this will mean that one of the champions of marine renewables will be outside the formal EU process. While it is comforting to perhaps draw on analogies with Norway, who remains so engaged with the EU and single market legislation that it sometimes described as a 'stealth member state', it seems that the evolving EU debate on marine renewables would be certainly the weaker for not having British advocates around the legislative drafting table in Brussels. In this context the direction and shape of specific EU rules on renewables might become more dominanted by German interests whose weight and influence on marine renewables is surely significant. It is worth stressing however, that each European country has a different experience of offshore wind and therein lies an important point of this paper: the centrality of the national level in explaining variation of high shares of offshore wind capacity. Time and space constraints preclude a full discussion of all states but I can make a few brief comments here about cases other than the British one. The German experience of offshore wind is now usually framed and understood as part of their national Energiewend, whose roots lie in domestic political competition and particularistic social risks perceptions. Whereas the French and Finns accept nuclear energy, a majority of Germans fear it. What is less well known is German domestic preferences have also skewed the pattern and scale of German offshore development. For planning reasons they have opted for far offshore wind parks in the North Sea (with some exceptions in the Baltic) and these are connected wth costly HVDC cabling. By way of contrast the rest of Europe prefes the bulk of their offshore windfarms closer to shore (within the 30km 5 The Crown Estate suggests that costs have fallen by 11% over the last three years for new developments. See: http://cleantechnica.com/2015/02/28/offshore-wind-costs-continue-fall-study/ FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 26 average) and typically these use HVAC cables. The result is Germany has not just chosen to go for offshore wind in a big way, but they have chosen to do so in the most expensive, risky and complex way, for domestic political reasons. Denmark's experience fits much more perfectly the ecological modernisation paradigm, as it was in Denmark that the first offshore windfarm was pioneered at Vindeby in 1991. Moreover, this experiment was pushed by very much the classic social network that brokered wind in Denmark: a local wind co-operative decided to diversify their devices from land to sea, in part concerned with planning constraints. Since then Denmark's engagement with offshore wind has been significant, and her industrial share of the global market for offshore wind turbines is much higher than for onshore wind. However, the Danes have been able to grow a very large share of wind, including the offshore portion, because of somewhat unique grid configuration. They are very heavily integrated with the Nordic electricity system and this provides them with a reliable and cheap way of balancing the intermittency problem that bedevils wind when it reaches high shares of capacity (typically between 20-30%). The same structural feature also applies to the Netherlands which have a less ambitious but still significant share of offshore wind planned as part of their national energy mix. Conclusion and Discussion. This paper has asked whether we should expect much for renewables from rhetoric about an EU Energy Union and whether we should be greatly concerned about the retreat from binding targets signaled in recent EU policy on renewables. We should be concerned that the EU appears less interested in promoting renewables in a more ambitious way but we should also be realistic in understanding that the logic of the single market, may ultimately clash with national willingness to subsidize green energy transitions. Moreover, the argument offered here has been that rather than see the EU as the decisive venue or series of actors whose influence is increasingly vital in making or breaking renewables, we should pay rather more attention to discrete national debates and institutional particulars. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 27 When we ask the question why some states are marine energy pioneers the answers seem clustered around the complex interaction of domestic political variables above all others. Britain has gone from being a laggard on renewables, to today becoming the global champion of marine renewables, to possibly in future losing that role because domestic governments fret more about costs and prefer other energy sources. This does not mean that what happens at the EU level is an irrelevance, but it suggests the weight of our empirical research and theoretical understanding should reflect the importance of the 'national' as regards renewables. Restrictions of space and time prevent a theoretical discussion as such here. However, it has become pretty standard to invoke the literature on Multi-Level Governance (MLG) as a means of capturing the dynamic interactions between Brussels, national capitals and subnational ambitions. In my view much of this literature has become insipid and describes policy activity, foremost networking between various levels, rather than explaining more decisive interventions. In particular the MLG approach is loath to privilege the national level, instead envisioning a catallaxy of networking between clusters of regional, national and EU level actors and institutions. MLG advocates point out the object of such activity may well agenda setting, information gathering and preference shaping rather than substantive decision-making (Piattoni, 2009, p.164). Arguably this simply downplays the fact that many of the most vital decisions, such as funding, are made by national governments. Even Calliess and Hey (2013) who explictly invoke an MLG perspective on the EU's role on renewables are forced to admit that decisive powers of decision remain at the national level above all others. It seems also mistaken to try and interpret the role of the EU and the Member States through a comparative politics perspective using the literature on federalism as a guide. For example, Wyns (et al, 2014, p. 18-20) specifically invoke a federal comparative analysis by questioning whether something like the US Renewable Portfolio Standard might work in an EU context. While this is an initiative led by US states, it sits within an overall policy system which is definitively a federal and national one. For example the US federal wind energy tax credit and other such incentives have been hugely important in American wind development. The EU has nothing like this for the very simple reason that it is not at all a FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 28 federation but is at best described as a weak confederation. The American governance system then for renewables is a poor analogy for the EU's situation, where fiscal measures remain national. One possibility may be to explore accounts that are increasingly labeled the 'new intergovernmentalism' (Puetter, 2014, Bickerton, et al, 2014). What is perhaps good about this literature is the focus on the EU's crisis of legitimacy or that EU leadership will be increasingly challenged as such. What is perhaps bad is that the debate on 'new intergovernmentalism' becomes somewhat fixated on a number of hypotheses about the style of current EU politics which it seeks to show are present: greater consensus, delegation, differences between high and low politics becoming blurred and so on. These may or may not be evident to a greater extent than 20 years ago when the 'permissive consensus' on European Integration reigned, but it tells us very little about what is going at the national level, and why some states are ambitious on marine renewables, and others, choose not to be. Therefore, it seems what we need are theoretical approaches which explain why national networks of key actors tend to form the preferences they do. In this regards diverse literatures on national varities of capitalism (Tienhaara, 2014), or national discourses of ecological modernisation (Cox and Dekanozishvili, 2015, Midttun, 2012) and national innovation systems (Verhees, , Wieczorek, et al., 2015) might all pay considerable dividends. Ecological modernisation in particular appears somewhat challenged by the case of offshore wind. Britain has only a limited wind turbine industry with assembly and sub-components the main products rather than manufacturing. The jobs dividend from Britains leadership on marine renewables is thus likely to be less than say in Germany and Denmark, where Siemens and Vestas continue to dominate the market for offshore wind devices. Despite it is Britain and not Denmark or Germany who have the most ambitious marine renewable policies, although the former are no slouches. Moreover, given that the costs of offshore wind have been so fundamentally unattractive for so long how could this be overcome? It seems key industry and government actors assumed those costs would be defeated in a manner analogous to onshore wind, and there was a belief that scale could be achieved at sea unlike planning constrained land. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 29 If some EU states persist with offshore wind and other marine renewables this paper suggests they should not expect that the EU will always rally to their support nor be a strong champion for such technologies. Indeed the direction of EU energy policy may be inconclusive, or at times actively hinder such a transition. The unremitting focus on free movement of capital, goods and services that has been the core of EU energy policy, may well eventually challenge and undermine national subsidies for offshore renewables. Greater interconnection and wider market access may on the one hand reduce the intermittency problem that bedevil offshore wind, but of course these trading cables also facilitate much greater volumes of cross border electricity. This means expensive offshore renewable electricity will face even more intense price competition from cheaper imported electricity, much of which will be generated by fracked gas, nuclear or other non-renewable means. Increased EU rhetoric on 'energy security' seems as likely to lead to an obsession with natural gas markets rather than encouraging nation states to build electricity capacity in their own territorial waters, for those who can. The EU favours indirect and market based energy security approaches rather than direct security through diversity and proximity of supply. Perhaps the best that can be hoped for is neutrality as regards renewable technologies, however, the evidence to date suggests that impartiality over transitions to sustainable technology is simply far too subtle a strategy. What is needed are quite crude protective spaces, a rich ecosystem of generous subsidies and fiscal supports, allied with long-term unwavering political commitment to effectively guarantee a market of sufficient scale to attractive serious investors. Deeply unfashionable as it may seem, picking technology winners, or at least placing bets on multiple transition pathways seems to be a clear lesson from how onshore wind emerged successively The legal and political problem is how much of such activity is consistent with Single Market rules? Marine renewables would seem to be one such technology bet worth backing, doubtless among others. Framing the problem this way suggests that rather than seeing renewables as a challenge for EU energy or climate policy what is as relevant is seeing renewables as a key part of FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 30 industrial green or blue growth strategies whose key variables are more likely to be decided and shaped by national systems of innovation and competitiveness. Relatedly the core issue is to what extent EU Single Market rules can be bent, twisted, avoided or openly broken to provide offshore renewables with a 'protective space' to grow to their potential, a transition that will take time. For now, renewables in general have been tolerated as an exception to the 'free movement' orthodoxy but a critical issue is whether this will in the future not be restricted. One avenue for limiting national scope could well be that national subsidy or support schemes will be required to have a certain minimum per cent of funding made available to renewable capacity suppliers from other member states (and probably vital EEA/EFTA countries like Norway and perhaps Iceland) (Szydło, 2015, p.506). As for the EU's leadership on renewables is seems churlish to suggest it has gone 'offshore' or is 'lost at sea' to continue poor nautical metaphors. However, the assumption that a harmonized policy on renewables is either possible or needed to push transitions needs to be critically re-examined. Moreover, the residual importance of national sovereignty in energy policy and renewables is anyhow proving to be much more important than many academics have heretofore admitted in their rush to lavish attention on headline grabbing initiatives such as the 2009 Directive. As Fischer and Gerdén suggest in their survey of EU energy politics around 2013: "The much more fundamental question, which is currently simmering under the surface, is whether Member States are going to be willing to surrender further parts of their sovereignty in the area of energy policy to the EU" (Fischer and Gerdén, 2013, p. 10). Bibliography Allan, G. Lecca, J.P., McGregor, P. G. and J. K. Swales. 2014. The economic impacts of marine energy developments: A case study from Scotland. Marine Policy, 43 (1), 122-131. Andersen, Allan Dahl (2014) "No Transition without Transmission: HVDC electricity infrastructure as an enabler for renewable energy?", Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Vol.13, pp.75-95. Benson, David, and Duncan Russel. "Patterns of EU Energy Policy Outputs: Incrementalism or Punctuated Equilibrium?." West European Politics 38, no. 1 (2015): 185-205. Bickerton, Christopher J., Dermot Hodson, and Uwe Puetter. "The new intergovernmentalism: European integration in the post‐maastricht era." JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies (2014). Calliess, Christian, and Christian Hey. "Multilevel Energy Policy in the EU: Paving the Way for Renewables?." Journal for European Environmental & Planning Law 10, no. 2 (2013): 87-131. Cox, Robert Henry, and Mariam Dekanozishvili. "German Efforts to Shape European Renewable Energy Policy." In Energy Policy Making in the EU, pp. 167-184. Springer London, 2015. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 31 Dawley, Stuart, Danny MacKinnon, Andrew Cumbers, and Andy Pike. "Policy activism and regional path creation: the promotion of offshore wind in North East England and Scotland." Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society (2015): rsu036. De Decker, Jan, and Achim Woyte. "Review of the various proposals for the European offshore grid." Renewable Energy 49 (2013): 58-62. De Jong, J., Egenhofer, C. (2014) Exploring a Regional Approach to EU Energy Policies. No. 84. CEPS Special Report. Brussles: Centre for European Policy Studies. European Commission, 2013d. Renewable energy progress report. Available at: 〈http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri COM:2013:0175:FIN:EN:PDF〉. Eurostat, (2014) Electricity generated from renewable sources. Available at: ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/table.do? Evans, S., 2014. Analysis: who wants what from the EU 2030 climate framework. The Carbon Brief. Available at: 〈http://www.carbonbrief.org/blog/2014/10/analysis-who-wants-what-from-the-eu-2030-climate-package/〉 EWEA/ European Wind Energy Association (2013) 2030: the next steps for EU climate and energy policy. A report by the European Wind Energy Association - September 2013. EWEA/ European Wind Energy Association (2013a) Where's the money coming from? Financing offshore wind farms a report by the European Wind Energy Association. Available at: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/reports/Financing_Offshore_Wind_Farms.pdf EWEA/ European Wind Energy Association (2014) Wind energy scenarios for 2020. July 2014. Available at: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/reports/EWEA-Wind-energy-scenarios-2020.pdf EWEA/European Wind Energy Association (2014a) 'Meeting the 2030 renewable energy objective thanks to a robust governance system'. Available: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/position-papers/EWEA-position-on-2030governance.pdf EWEA/ European Wind Energy Association (2015a) The European offshore wind industry - key trends and statistics 2014. January 2015. Available at: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/statistics/EWEA-European-Offshore-Statistics2014.pdf EWEA/ European Wind Energy Association (2015b) Wind in power 2014 European statistics. February 2015. Available at: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/statistics/EWEA-Annual-Statistics-2014.pdf EWEA/European Wind Energy Association (2015c) The European offshore wind industry - key trends and statistics 1st half 2015. Available at: http://www.ewea.org/fileadmin/files/library/publications/statistics/EWEA-European-Offshore-Statistics-H12015.pdf Fauconnier, Jean-François (2015) 'The Commission must give teeth to the 2030 Renewable Target', Euractiv, June 16th, available at: http://www.euractiv.com/sections/climate-environment/commission-must-give-teeth-2030-renewable-target315439 Fischer, Sevrin and Oliver Geden (2013) "Updating the EU’s Energy and Climate Policy." New Targets for the Post-2020 Period, Berlin: German Institute for International and Security Affairs (2013). Available at: http://www.ies.be/files/eu_renewable_energy_governance_post_2020.pdf Flynn, Brendan (2015) ‘Ecological modernisation of a Cinderella renewable? The emerging politics of global ocean energy’, Environmental Politics, 24:2, 249-269. Flynn, Brendan (2016) 'Transforming Europe’s Marine Renewables through a North Sea Offshore Grid: a sustainability transition too far?', forthcoming. Giuli, Marco. "The Energy Union: what is in a name? EPC Commentary, 18 March 2015." (2015). Hildingsson, Roger, Johannes Stripple, and Andrew Jordan. "Governing renewable energy in the EU: confronting a governance dilemma." European Political Science 11, no. 1 (2012): 18-30. Jacobsson, Staffan, and Kersti Karltorp. "Mechanisms blocking the dynamics of the European offshore wind energy innovation system–Challenges for policy intervention." Energy Policy 63 (2013): 1182-1195. Jacobsson, Staffan, Anna Bergek, Dominique Finon, Volkmar Lauber, Catherine Mitchell, David Toke, and Aviel Verbruggen. "EU renewable energy support policy: Faith or facts?." Energy policy 37, no. 6 (2009): 2143-2146. Jacobsen, Henrik Klinge, Lise Lotte Pade, Sascha Thorsten Schröder, Lena Kitzing (2014) Cooperation mechanisms to achieve EU renewable targets, Renewable Energy 63, 345-352 FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 32 Jay, Stephen (2012) "From Laggard to World Leader: The United Kingdom’s Adoption of Marine Wind Energy.", pp.85-107 in Szarka, J., Cowell, R., Ellis, G., Strachan, P. & C. Warren (Eds.): Learning From Wind Power. Governance, Societal And Policy Perspectives On Sustainable Energy. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. Johnston, Angus (2010) ' How binding are the EU’s ‘binding’ renewables targets? A Legal Perspective', paper presented at the European Electricity Workshop (CEEPR/EPRG), Berlin, 15th July, 2010. Available at: http://www.eprg.group.cam.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/Johnston.pdf Kaldellis, J. K., and M. Kapsali. "Shifting towards offshore wind energy—Recent activity and future development." Energy Policy 53 (2013): 136-148. Kern, Florian, Adrian Smith, Chris Shaw, Rob Raven, and Bram Verhees. "From laggard to leader: Explaining offshore wind developments in the UK." Energy Policy 69 (2014): 635-646. Kern, Florian, Bram Verhees, Rob Raven, and Adrian Smith. "Empowering sustainable niches: Comparing UK and Dutch offshore wind developments." Technological Forecasting and Social Change (2015), article in press. Kitzing, Lena, Catherine Mitchell, and Poul Erik Morthorst. "Renewable energy policies in Europe: Converging or diverging?." Energy Policy 51 (2012): 192-201. Knopf, Brigitte, Paul Nahmmacher, and Eva Schmid. "The European renewable energy target for 2030–An impact assessment of the electricity sector." Energy Policy 85 (2015): 50-60. Knudsen, Jørgen (2012) "Renewable energy and environmental policy integration: renewable fuel for the European energy policy.", pp.48-65 in Morata, Francesc and Isarel Solorio Sandoval (eds.) European Energy Policy: An Environmental Approach, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham. Lauber, V. (2013) ‘Current and upcoming challenges for Germany’s Energiewende’ Presentation to Science Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex Lauber, Volkmar, and Staffan Jacobsson. "The politics and economics of constructing, contesting and restricting socio-political space for renewables–The German Renewable Energy Act." Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions (2015). Lynch, Suzanne (2014) 'European Commission Scraps Renewable Targets', Irish Times, Wednesday January 22nd, 2014. Mcewen, Nicola, and Elizabeth Bomberg. "Sub-state climate pioneers: the case of Scotland." Regional & Federal Studies 24, no. 1 (2014): 63-85. Midttun, A. 2012. The greening of the European electricity industry: a battle of modernities, Energy Policy, 48, 22-35. Peeters, Marjan (2015) "Perspectives on current and future EU Renewable Energy law", The Future of the European Union's renewable energy law and its impact on Member States, University of Edinburgh, Environmental Law Lecture Series, February 2015. Available at: http://www.law.ed.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/171500/EU_Renewable_Energy_Law_Edinburgh_.pdf Piattoni, Simona (2009) ‘Multi-level Governance: a historical and conceptual analysis’, European Integration, Vol.31, No.2, pp.163-180. Puetter, Uwe. The European Council and the Council: New Intergovernmentalism and Institutional Change. Oxford University Press, 2014. Umpfenbach, Katharina, Andreas Graf, and Camilla Bausch. "Regional cooperation in the context of the new 2030 energy governance." (2015). Scharpf, Fritz (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford: OUP Strachan, Peter, Alex Russell, Ian Broadbent (2014) "Scottish wind could fix UK energy woes – don’t let Westminster blow it", The Conversation, September 23, 2014 12.09pm BST. https://theconversation.com/scottish-wind-could-fix-uk-energy-woes-dont-let-westminster-blow-it-31532 Strachan, Peter and Ian Broadbent (2015) 'All at sea! UK government is putting future offshore wind at risk', EnergyPost.eu, July 7th, available at: http://www.energypost.eu/sea-uk-government-putting-future-offshorewind-risk/ Strachan, Peter and Alex Russell (2015) 'Tories are backing the wrong horses when it comes to energy', The Conversation, June 23, 2015 9.31pm BST. https://theconversation.com/tories-are-backing-the-wrong-horseswhen-it-comes-to-energy-43746 Szydło, Marek. "How to reconcile national support for renewable energy with internal market obligations? The task for the EU legislature after Ålands Vindkraft and Essent." Common Market Law Review 52, no. 2 (2015): 489-510. Toke, D., Sherry‐Brennan, F., Cowell, R., Ellis, G., and Strachan, P. (2013) Scotland, Renewable Energy and the Independence Debate: Will Head or Heart Rule the Roost? The Political Quarterly, 84(1), 61-70. Toke, David (2011) 'The UK offshore wind power programme: A sea-change in UK energy policy?', Energy Policy, Volume 39, Issue 2, February 2011, Pages 526–534. FLYNN-UACES, Bilbao, 7-9 September 2015 "Brussels Offshore? Explaining the largely national politics of Europe's experiment with marine renewables." 33 Vaughan, Adam (2015) 'UK and France 'may miss EU renewable energy target', The Guardian, June 16th, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jun/16/uk-misses-eus-interim-renewablestarget Verhees, Bram, Rob Raven, Florian Kern, and Adrian Smith. "The role of policy in shielding, nurturing and enabling offshore wind in The Netherlands (1973–2013)." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 47 (2015): 816-829. Wettestad, Jørgen, Per Ove Eikeland, and Måns Nilsson. "EU climate and energy policy: A hesitant supranational turn?." Global Environmental Politics 12, no. 2 (2012): 67-86. Wieczorek, Anna J., Simona O. Negro, Robert Harmsen, Gaston J. Heimeriks, Lin Luo, and Marko P. Hekkert. "A review of the European offshore wind innovation system." Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 26 (2013): 294-306. Wieczorek, Anna J., Marko P. Hekkert, Lars Coenen, and Robert Harmsen. "Broadening the national focus in technological innovation system analysis: The case of offshore wind." Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 14 (2015): 128148. Wintour Patrick and Adam Vaughan (2015) 'Tories to end onshore windfarm subsidies in 2016', The Guardian, Thursday 18th June, available at: http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/jun/18/tories-end-onshore-windfarm-subsidies2016 Woerdman, Edwin, Martha Roggenkamp, and Marijn Holwerda (eds.) (2015) Essential EU Climate Law. Edward Elgar Wyns, Tomas, Arianna Khatchadourian and Sebastian Oberthür (2014) EU Governance of Renewable Energy post-2020 – risks and options. A report for the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung European Union. Brussels: Institute for European Studies - Vrije Universiteit Brussel. About the author. Brendan Flynn is a lecturer within the School of Political Science & Sociology, National University of Ireland Galway. His Masters and PhD degrees are from the University of Essex. His doctoral topic was: "Subsidiarity and the Evolution of EU environmental policy". Dr. Flynn's teaching and research interests are focused on environmental and marine policies, with a recent major research project being the Irish Fishers' Knowledge Project (2008-2013). He is the author of "The Blame Game: Rethinking Ireland's Sustainable Development and Environmental Performance" (Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2007) and a co-author of "Environmental Governance in Europe: An Ever Closer Ecological Union?” (Oxford: OUP, 2000). His most recent publication is: Flynn, Brendan (2015) ‘Ecological modernisation of a Cinderella renewable? The emerging politics of global ocean energy’, Environmental Politics, 24:2, 249-269.