SEXUAL HARASSMENT FEDERAL WORKPLACE

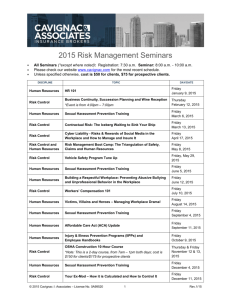

advertisement