Development beyond the Central City: Eco-Infrastructure in Ulcinj, Montenegro

advertisement

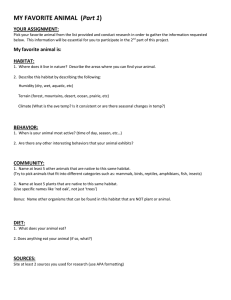

Development beyond the Central City: Eco-Infrastructure in Ulcinj, Montenegro Gretchen Mikeska and John Tabor IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 December 2009 Development beyond the Central City: Eco-Infrastructure in Ulcinj, Montenegro Gretchen Mikeska and John Tabor December 2009 Abstract The principal objectives and scope of the current study are to examine how eco-infrastructure can be sustained within a multiuse area of a municipality in a transition economy in a way that protects habitat, ensures public access, and is adequately funded and managed. The case of Ulcinj, Montenegro, is presented for this purpose. The methodology employed reviews the available literature and best practices to identify possible models, and then considers them in the context of Ulcinj for their relevance and feasibility. The comparative analysis identifies six examples of nature preserves that successfully protect habitat, ensure public access, and operate sustainably with adequate funding and management. The examples are taken from California, Croatia, Chile, Bolivia, Costa Rica, and Guatemala. The principal conclusions from the study are that, even though there are formidable challenges to resolve, models do exist which can be adapted and applied in Ulcinj, Montenegro. One approach that is particularly promising is the use of conservation easements that ensure the preservation of habitat and public access through payments to land owners derived from various sources. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 Development beyond the Central City: Eco-Infrastructure in Ulcinj, Montenegro Gretchen Mikeska and John Tabor December 2009 1. Context Montenegro has long understood that tourism, particularly coastal tourism, is key to its longterm economic prosperity. Travel and tourism’s contribution to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to rise from 26 percent in 2008 to 31 percent by 2018. Increasing the tourism sector’s contribution is even more important considering Montenegro’s recent independence from Serbia and its goal of European Union (EU) membership. Due to its natural habitats, cultural attractions, and diverse landscapes, Montenegro should be able to further increase the tourism sector’s contribution to GDP. While its focus has previously been on economic tourism, luxury and ecological tourism are likely areas of significant sector growth. The wildlife habitat of Ulcinj is important for additional reasons. It is a key link in the flyway of birds that migrate between northern Europe and North Africa twice per year. These birds depend on the Ulcinj habitat to rest and feed in preparation for their next flight. If this habitat is removed, some species may become extinct while others may decline in population. As part of the World Bank’s Montenegro Sustainable Tourism Development Project, the assignment “Preparation of the Final Design for Eco-Infrastructure in the Bojana Delta” was undertaken in 2008 by the Urban Institute (United States) and Hydro-Engineering Institute Sarajevo (HEIS). Successor projects plan to construct the eco-infrastructure in Ulcinj, Montenegro, according to designs developed by this project. Project supporters believe Ulcinj has the environmental assets to attract a major ecotourism industry. Wildlife habitats for waterfowl and migrating bids, sea turtles, and exotic plants can be connected with foot and bicycle trails along the Ulcinj coast and Bojana River, supported by an information center. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 1 2. Objectives of the study To assess how the eco-infrastructure can be continually sustained in the case of Ulcinj, Montenegro, this paper will study international experiences and consider three aspects of sustainable eco-infrastructure: First, what experiences exist with regard to protecting wildlife habitats on lands being developed as resorts and adjacent private property? Habitat that must be maintained in its natural condition may cut across various properties, requiring special measures applied to multiple owners. Second, what do current practices suggest about ensuring long-term public access to publicly funded eco-infrastructure on or near private properties? Unless specific provisions are made in the case of Ulcinj, eco-infrastructure could become inaccessible due to resort development and private property restrictions. Third, what options exist for financing and operating the eco-infrastructure? For example, user fees, stakeholder fees, and business fees from the new eco-infrastructure could fund the ongoing operating costs. 3. Comparative international experiences The development of eco-infrastructure in support of a successful ecotourism strategy almost always involves a broad set of stakeholders and requires balancing the various –sometimes competing- interests of the different stakeholders. Table 1 presents an overview of the main interests and concerns as viewed by the key stakeholders in Ulcinj, including the municipal government and other government entities, the private sector, and the local environmental community. Table 1. Framework for Evaluating Sustainable Tourism Projects—The Case of Ulcinj, Montenegro GOAL To Provide Eco-Infrastructure for Sustainable Ecotourism Key stakeholders Values and priorities National and municipal governments and coastal commissions • Increased national and local economic development • Increased government revenues • Improved public services IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 Resort, business, and property owners • • • Increased investment opportunities Increased business formation and growth Greater income and profits Environmental, community development institutes and NGOs • Protected valuable habitat, flora and fauna • Ensured public access • Increased local jobs and quality of life 2 Strengths • • • Weaknesses • • • • • Opportunities • • • Constraints • • • Issues and objectives: how to--- • • • Attractive location for exclusive resorts Interest of international resort developers Interest of international tourism organizations • Inadequate public services and infrastructure Inadequate revenues Deficient regulation Fragmented land ownership Overlapping jurisdictions • Growing market for luxury tourism Expressed interest of major investors Favorable image of Montenegro for tourism Global financial crisis Competing interests of luxury and ecotourism Nature protection requirements for entry to EU Attract resort developers with land acquisition, zoning, tax incentives, regulation Provide supporting public services and infrastructure Form public-private partnerships • IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Attractive location for exclusive resorts Supportive government policies and incentives Investor interest Supportive local business community • Lack of experienced local partners Lack of experience with integrated resort—ecotourism development Fragmented land ownership Untrained work force Inadequate infrastructure Growing market for luxury tourism Improved capital access Few alternate locations for luxury resorts Global financial crisis Competing uses of habitat for luxury and ecotourism Increasing litter and pollution • Establish exclusive resorts Increase tourist attractions Provide supporting services for increased tourism Generate income from ecotourism • • • • • • • • • • • • • Valuable natural habitat, flora, and fauna Strong potential for ecotourism Interest of international and local institutes and NGOs Limited influence on public policy Limited capacity for joint action Fragmented land ownership Lack of funds for land acquisition and research Growing market for ecotourism Growing interest of EU and international groups in ecotourism Excessive hunting, development, and public use of habitat Litter and pollution Use of habitat for luxury resorts Finance operation, maintenance and repair of ecoinfrastructure Organize and operate eco-infrastructure and services, implement management plan Manage success (many ecotourists) to avoid habitat destruction 3 As a result, a combination of different interventions and options will likely be needed to sustain the proposed eco-infrastructure. Options and planning approaches that may need to be pursued in the development of an eco-infrastructure plan for Ulcinj include the following: • • • • • • • • • • Confining trails and facilities, when possible, to publicly owned land; Swapping publicly owned developable land with privately owned land to be set aside for habitat and ecotourism trails and facilities; Requiring pubic access to eco-infrastructure facilities located on resort lands; Purchase of land needed for wildlife habitat and eco-infrastructure by the Government of Montenegro (GoM) land banks, or international environmental organizations; Expropriation of private land for habitat and eco-infrastructure; Maintaining eco-infrastructure through public-private partnerships (PPPs) that will operate and maintain the facilities by charging user fees and selling concession goods to tourists; Obtaining easements from landowners that host critical wildlife habitat and ecoinfrastructure; Conducting scientific assessments of plant and wildlife conditions initially and periodically thereafter to determine whether the habitat is being maintained or is deteriorating; Preparing and implementing management plans to ensure appropriate levels of usage and environmental protection; Generating sufficient revenues to sustain operations, maintenance, and repair. To assess the viability of these different options and approaches, a survey of international experience contained in relevant literature is presented in this section. These international practices are a good representation of the spectrum of policy alternatives available in the pursuit of sustainable eco-infrastructure. Consideration of each case will broadly be made within the framework defined in table 1 for the Ulcinj case. Application of these experiences to Ulcinj and conclusions follow in sections 5 and 6. Ellwood-Devereux Coast, Santa Barbara, California This nature preserve has an open space and habitat management plan for a contiguous 652-acre open space and natural area that provides for habitat preservation and public access. Its partners include the city and county governments, a state university, and a private housing developer. Habitat—Local officials placed publicly owned land held by three jurisdictions under one integrated master plan. They also arranged land swaps to trade public property for private property. The private developers were allowed to develop the traded property while the public authorities reserved the property they acquired to be open space. The land traded to developers was close to existing developments, thereby improving the efficiency of public services and minimizing the environmental impact of development. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 4 Public Access—Long-term public access to publicly funded trails and facilities and protection of habitat for flora and fauna was accomplished partially through placement of trails on publicly owned open space and partially through negotiated easements with surrounding property owners. Nature trails were located for viewing of interesting flora and fauna, while avoiding sensitive habitat. Finance and Operation—The construction, operation, and maintenance of the site comes from partner budgets, public and private grants, bond sales, fees, and philanthropy. Reference—This plan can be viewed online on the web site of the University of California, Santa Barbara. 1 Crna Mlaka Ornithological Reserve, Croatia The Crna Mlaka Ornithological Reserve is near Zagreb, Croatia. It is a large and important sanctuary for water birds and migratory birds, which feed and breed there. It has an artificial wetland environment resulting from long-term aquaculture. Its bird population is considered at risk due to a decline of fish production. It may offer useful information as new developments in Solana (Salt Works) Ulcinj affect its resident and migrating water fowl. Habitat—There are 14 carp production ponds in the reserve, and they are critical to the survival of the birds. The carp ponds previously operated on a commercial basis, but due to poor marketing and high water taxes, the carp ponds are not profitable, and many have fallen into ruin. Public Access—Public access is being increased to contribute to the financial health of the park. Finance and Operation—A new management plan has important provisions for public and private uses of the ponds, including commercial production of carp and other fish, sport fishing, and ecotourism, each which would be a source of funding for support of the reserve. Reference—Additional information is available http://www.mzopu.hr/doc/Neap/44 Crna Mlaka.pdf. on the Crna Mlaka web site, The Valdivian Coastal Reserve of Chile and the Eduardo Avaroa National Park of Bolivia The Valdivian Coastal Reserve protects 147,500 acres of biologically rich temperate rainforest in the Valdivian Coastal Range. The Eduardo Avaroa National Park protects flocks of flamingos in a volcanic environment. The Valdivian rainforest was in danger of being cut for timber, as had happened in other parts of the range. The Avaroa National Park was underfunded and poorly managed, with environmental damage caused by indiscriminate usage and pollution. In each case, the Nature Conservancy was able to assist local environmentalists. 1 http://facilities.ucsb.edu/_client/pdf/planning_ellwood/documents/OSP/Draft_OSP_0304_complete.pdf IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 5 Habitat—The Nature Conservancy joined with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the Chilean government, NGOs, and communities to purchase and manage the Valdivian Coastal Reserve. It is now seeking a private buyer to purchase its forestland. Funds from the land sale would be used to establish a foundation that manages the reserve. It will also assign a portion of the forest to the government for operation of a national park. Public Access—Easements for public access are being made a condition of resale of the Valdivian Reserve and of the agreement to donate land to the Chilean government for a national park. Historically, the major problem at Eduardo Avaroa National Park of Bolivia was uncontrolled access and usage. The Nature Conservancy prepared a scientific assessment and management plan which set guidelines and locations of usage within the park. Finance and Operations—The Nature Conservancy designed self-funding systems to pay for the operation and maintenance of the protected areas, which includes user fees and concessions. The management plan contains an operating budget and provides for park rangers, sanitation services, and other support required to keep the park in its natural condition. Reference—More information on the Valdivian Coastal Reserve of Chile and the Eduardo Avaroa National Park of Bolivia is available from the Nature Conservancy. 2,3 The World Bank–Funded Costa Rica Ecomarkets Project This World Bank–funded Costa Rica Ecomarkets Project was one of the first projects to recognize and pay for conservation values associated with natural forests. The project built on preceding efforts funded by the Costa Rican government and donors. Lessons learned from it have been shared by the World Bank with other nations in Latin America, Africa, and Central Asia. A government agency, the National Forestry Financing Fund (FONAFIFO), entered agreements with private land owners that established conservation easements to protect and enhance their forests. The land owners were paid periodically for the value their forests contributed to biodiversity, carbon sequestration, hydropower generation, preservation of watersheds for water users, wild life refuges of interest to ecotourists and others, buffer zones for national parks, and for reforestation and afforestation, in keeping with the Kyoto Protocol. Habitat—The forests were viewed as more than wildlife habitat and were valued for other benefits, such as carbon sequestration, which compensated for air pollution caused by vehicle exhaust. Three and a half percent of the national tax on gasoline was contributed to the FONAFIFO. The value of the wildlife habitat was monitored through periodic censuses of key species, such as spider monkeys, Baird’s tapirs, great curassows, and tinamous. Public Access—Public access to the forests was provided through the ecotourism industry. 2 3 http://www.nature.org/aboutus/howwework/src=t2 http://www.nature.org/magazine/autumn2006/forests/art18590.html IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 6 Finance and Operations—Since the ecological benefits encompassed more than ecotourism, the costs was spread among vehicle users, hydropower companies, municipal water suppliers, and others, in addition to ecotourism operators. Also, reforestation was compensated by the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol. The German Development Bank (KfW) and Conservation International were also involved. A World Bank grant was provided to give sufficient time for the revenue collection and payment institutions and mechanisms to become established and self-sustaining. References—More information on the Costa Rica Ecomarkets Project is available from the World Bank. 4, 5 Debt-for-Nature Swaps Habitat, Finance and Operations—Debt-for-nature swaps are a mechanism to sustain long-term conservation efforts in countries with forests of great natural value and which have a large foreign debt. Under the Tropical Forest Conservation Act of 1988 (United States), eligible countries agree to use their debt payments to finance tropical forest conservation in their own countries. The creditor discounts or forgives the debt in return for a commensurate contribution by the debtor nation to a national trust fund that sponsors conservation programs. The Nature Conservancy has participated in a number of these swaps, including those for Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Jamaica. The Guatemala deal is the largest debt-for-nature swap yet under the Tropical Forest Conservation Act (United States) and the fifth swap facilitated by the Conservancy. With this debt-for-nature swap, the Nature Conservancy will be able to magnify its conservation efforts in Guatemala. The Nature Conservancy raised $1 million in the United States toward the deal, $500,000 of which was donated by American Electric Power and $200,000 by the Nature Conservancy’s Maine program. The U.S. government is providing $15 million toward the agreement. These funds were used to purchase much larger amounts of debt owed by these countries to the United States Government. The countries then paid the amounts previously paid to the U.S. Treasury into conservation trust funds. These trust funds are then used by the borrower nation to demarcate valuable forests and conserve them. Reference—More information is available from the Nature Conservancy 6 4 http://www2.gsu.edu/~wwwcec/docs/doc updates/NCSU_Blue_Ribbon_Panel_Final.pdf. http://www.wds.worldbank.org/external/default/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2007/03/21/ 000020953_20070321110303/Rendered/PDF/ICR433.pdf. 6 http://www.nature.org/pressroom/press/press2641.html. 5 IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 7 4. Discussion and analysis: applications for Ulcinj Municipality The comparative experience outlined above has several common themes. In each case, valuable natural habitat was in danger of being lost to various kinds of development, exploitation, or neglect. Also, public access to the habitat was uncertain or unmanaged. Finally, there was no sustainable means to protect and sustain ecotourism and supporting eco-infrastructure. The solutions to these problems involved the acquisition of habitat through public and private initiatives, preparation and use of conservation plans and business plans, and legal provision for public access easements. These solutions could conceivably help the GoM, Ulcinj Municipality, and its stakeholders to address similar situations. Each solution is examined in greater detail below, with contributions from relevant literature and with consideration of conditions in Ulcinj. Protection of Habitat In Ulcinj Municipality, portions of the valuable wildlife habitat are owned respectively by the national government, the municipality, a large private salt works (Solana Ulcinj), and numerous private owners of small properties. In addition, the Morsko Dobro (a coastal commission) controls usage of a wide band of coastal property. Overlaid on these lands are several national and municipal development plans and policies that regulate land use. In addition, illegal use of land for private vacation homes and businesses, sand pits, ambient garbage, unrestricted usage by tourists, and out-of-season and excessive hunting add to the difficulty of protecting wildlife habitats, as well as flora and fauna. A study for a proposed new nature preserve has been prepared by an environmental consultant, and a complimentary eco-infrastructure design by the Urban Institute is under way. The new national and municipal initiative to develop exclusive resorts with private investment on some of the same properties completes the range of interests that must be reconciled and integrated, if upscale tourism, ecotourism and infrastructure are to be harmonized and sustained. A number of options for successful integration of these competing land uses are described below. • Joint Review Panel, MOU, and Management Plan. Similar to the initiative of the City of Goleta, County of Santa Barbara and University of California—Santa Barbara (refer to the Plan located at the Reference footnote 1). • Land Swaps. Since the GoM owns considerable land in Ulcinj, it may be able to reach agreements with land owners to swap parcels that are important for conservation for other parcels that offer commensurate benefits, such as residential or commercial potential. The GoM has the power of eminent domain, but appears reluctant to use it. • Land Trust. At present, the largest single private property in Ulcinj contains the most abundant bird population. The Bajo Sekulic Salt Company (Solana Ulcinj) owns 1,500 hectares of salt pans and surrounding wetlands and channels with prime habitat. The environmental NGO EuroNatur prepared a management plan for it several years ago which has not yet been adopted. The land is now scheduled to be sold to the developer chosen by the GoM for primarily tourism uses, such as a resort, golf course or airport – all which could have significant negative impact on habitat and the birds living there. One alternative could IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 8 be to enhance the salt works’ value to tourists as a nature preserve held and operated by a Land Trust. Like the Crna Mlaka fish ponds in Croatia, Solana Ulcinj must continue its salt work operations to maintain the habitat for birds. A Land Trust could assist in this effort. A Land Trust could also buy other privately-owned prime habitat in Ulcinj Municipality, such as the forest corridor that parallels the Bojana River, as well as the shores of Lake Šas. “Land trusts, also called conservancies, are private non-profit organizations that protect land directly, by owning it.” 7 Land Trusts operate internationally, regionally and locally, in accordance with their charters. The Nature Conservancy is an example of an international Land Trust. • Conservation Easements. The example above for conservation easements in Costa Rica could be a worthy option for protecting and enhancing wildlife habitat and forests in Ulcinj. Since Solana Ulcinj is a major property in Ulcinj, a business operated by a private company, and is home to invaluable bird species, the company could be paid periodically to protect its property from conflicting uses that could damage the habitat. This additional income could make it worthwhile from a business perspective to avoid selling it for resort development. Also, the forest corridor along the Bojana River, the vicinity of Šas Lake, and parts of Velika Plaža could be protected with similar conservation easements for private property. A portion of the gasoline tax and tourism taxes might be funding sources for these payments. Payments by the municipal water utility might also be made to help protect the watershed. An independent organization would be required to administer the funds received from taxes and fees charged to users and beneficiaries of the habitat. Since the World Bank made a grant to the Costa Rican management organization to allow it time to become established and implement revenue collection means, perhaps it might do so for Ulcinj as well. • Debt for Nature Swaps. This device for funding conservation by foreign debt payments has been used successfully in several countries, such as those named above. The World Bank is the largest creditor to Montenegro, holding 187.1 million Euros of its debt stock as of the end of 2008. 8 It could conceivably participate with conservation groups in a debt-for-nature swap for conservation of natural assets in Ulcinj. The funds could be used for land acquisition, easement payments, conservation education, and operation and maintenance of ecoinfrastructure. This option may work well as long as the priorities of the debtor country (Montenegro) match those of the donors and creditors involved in the debt-for-nature swap. Uncontrolled or Uncertain Public Access to Habitat Some of the prime property along the Bojana River has been used for construction of illegal cottages. Some beach-side businesses have been built in sensitive dunes and bird habitat. Visitors drive and park on the dunes, and litter as well. The Eduardo Avaroa National Park in Bolivia and the Ellwood-Devereux Reserve in California offer examples of how a management plan can 7 Brewer, Richard. 2003. Conservancy: The Land Trust Movement in America. Hanover and London: University Press of New England. 8 www.gov.me/files/1232363628.xls IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 9 restrict visitors to certain paths and areas that provide interesting views without disturbing the wildlife and habitat, maintain order with park rangers, and ensure a clean environment through services paid from visitor fees charged by the Park administration. When the exclusive resorts are being designed, an environmental management plan, visitor trails and observation facilities could be prepared with participation all major stakeholders, including GoM agencies, the municipality, resort developers, and nature and community development groups. Public access could thus be assured for prime wildlife habitat while allowing the resort developers to reserve their facilities for the exclusive use of guests. This is the current focus of The Urban Institute’s project in Ulcinj. Underfinanced and Unmanaged Habitat and Infrastructure Velika Plaza has been a dumping ground for many years. Part of the problem seems to be caused by a division of responsibility between Morsko Dobro, which collects revenues from touristrelated businesses, and the municipality of Ulcinj, which is responsible for solid waste removal and disposal. There appears to be no sharing of revenues or contracting of cleaning services between Morsko Dobro and the municipality. The successful examples of nature preserves cited above indicate a combination of scientific and management plans can be the basis for systematic care of habitat and infrastructure. Equally important are the provision of an empowered organization, with funds and a capable staff that implements the plans. Revenues from reliable and continuous sources make the management of these natural habitats sustainable. BRL Ingénierie produced a plan for creation of a nature preserve in Ulcinj. This plan includes a scientific assessment of flora and fauna and proposal for protection of wildlife and their habitat. If this plan is approved by the GoM, it can provide the scientific basis for a management plan, and the creation of an institution responsible for management of Ulcinj’s sensitive habitat and appropriate eco-infrastructure. The present division of labor among government entities in Ulcinj indicates that a unified organization should be responsible for overall management of habitat and eco-infrastructure. The municipality currently has an office responsible for local economic development. Perhaps it can be the nucleus for such an organization. If bridge funding similar to that granted by the World Bank to the Costa Rican National Forestry Financing Fund can be obtained, this could finance the period where a new organization responsible for management and finance of the nature preserve and eco-infrastructure can be created and become effective. A consensus-based process that includes all the key stakeholders may produce the required harmonization of interests in a plan that combines a nature preserve with eco-infrastructure and several exclusive resorts. Since the number of stakeholders would be large and potentially unwieldy, the planning process could utilize a variant of the Large Scale, Real-Time Strategic IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 10 Planning model 9 . This model is often used with large complex organizations. The municipality of Ulcinj would be considered the organization in question, while GoM ministries, Morsko Dobro, resort developers, property owners, local business leaders, and scientific and civic NGO’s would be the major stakeholders. The strategic planning process could begin as soon as the developers of Velika Plaza and Ada Bojana are selected by the GoM and the conceptual designs for the resort development are prepared by the developers. An exercise of several days duration would then be held where the resort, nature preserve, and eco-infrastructure plans would be presented to all major stakeholders. Small mixed groups of stakeholders would analyze all plans with the assistance of experts and facilitators. Each group would make a list of features of the plans that were accepted by all group members, features that had issues that needed to be resolved, and changes that would make the plans even better. The small groups would present their findings in a plenary session, with facilitators organizing questions and comments. Following the plenary session, the developers would meet separately to decide which changes could be made and which could not. The developers would then make final presentations of their plans to the stakeholders. To the extent that the plans were congruent, they would be implemented. Those plans or parts of plans that still had unresolved issues would be referred to binding arbitration. This process would only work if all major stakeholders agreed to use it in its entirety before the process began. 5. Results Of the options described in section 3, progress has been made to address these deficiencies and may offer models for use in Ulcinj, Montenegro. • In California, much of the valuable habitat was already in public ownership but managed separately by two local governments and a university. Other valuable habitat was owned by a private developer who was about to build a large residential project on it. These conditions combined to threaten a delicate and important coastal habitat. • The land in Chile was in private hands and required purchase and protection to avoid exploitation. The habitat in Croatia was being lost due to failing commercial aquaculture. Ulcinj is losing habitat due to a variety of causes (e.g., proposed resort development, declining salt industry, unmanaged use). • Funds were made available in Chile through a conservation fund of the Nature Conservancy, along with contributions by others. The Conservancy operates a revolving fund that accepts donations of money and property, estate bequests, and other instruments such as IRAs that take advantage of American tax concessions given for private contributions to public causes. The revolving fund purchases endangered wildlife habitat, 9 Osborne, David, and Peter Plastrik. 2000. The Reinventor’s Fieldbook: Tools for Transforming Your Government. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 549-553. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 11 creates a management plan for it, places requirements for controlled public access to it, and then seeks one or more private buyers who will hold the habitat in trust. The funds generated by the resale of this land then returns to the revolving fund for use with future purchases of habitat. • In Bolivia, excessive usage was degrading the environment. The second theme was that public access to the habitat was uncontrolled and unprotected by law. The third theme was a lack of viable plans for sustainable ecotourism and operation and maintenance of supporting infrastructure. • Costa Rica reversed a long trend toward cutting the forests that had enormous ecological value. It did so by eliminating the incentives that landowners had to gain income from logging, ranching, agriculture and commercial development the land. It replaced those sources of income with payments that rewarded them for retaining the natural values of their forests, such as carbon sequestration, biodiversity, watershed preservation, and ecotourism. • Guatemala and other countries have used debt for nature swaps brokered by NGOs such as the Nature Conservancy and sponsored by large creditors holding the countries’ foreign debt, such as the U.S. Treasury and the World Bank. Montenegro has not used this mechanism to fund nature protection, but it does owe a substantial foreign debt to the World Bank and might seek a nature-debt swap. • To our knowledge, no strategic planning process combined with binding arbitration has been attempted for large scale organizations. But if all major stakeholders agree to use it, the process could be effective and feasible. Given the consequences of doing nothing (e.g., loss of essential habitat, lack of appropriate local economic development) the effort would certainly be warranted. 6. Conclusions The comparative experience reported in this paper of successful management of nature preserves, valuable habitat, and eco-infrastructure in other countries strongly suggests that Ulcinj can become a center of sustainable ecotourism. Much work will be needed to build a consensus among the disparate stakeholders as to the extent and location of a nature preserve in Ulcinj, the design and goals of eco-infrastructure that will promote sustainable ecotourism throughout Ulcinj Municipality, and how this will be harmonized with resort development. The questions of what property will be included; how public access will be secured, managed, and sustained; how it will be operated and maintained; and what will be the short- and long-term sources of funding will need to be fully resolved. Assembling the properties needed for a nature preserve and further reaching eco-infrastructure system (e.g., walking and biking trails, visitors center, observation towers) might be most easily IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 12 accomplished using the incentives adopted in Costa Rica. Under this scenario, no land swaps, expropriation of property, or uncompensated easements would be necessary. Owners of private properties, including the exclusive resorts operating on long-term leases, would be compensated for protecting and preserving the natural habitat on their lands. Their compensation would recognize the broader benefits to society of their natural assets, such as carbon sequestration, watershed preservation for water supply, ecotourism, and tourism related businesses. Their contributions and compensation would be specified in conservation easements that would be legally binding. Revenue streams would need to be identified and assigned to the organization responsible for managing the preserve and infrastructure. Sufficient bridge funding from the GoM and/or donors should enable a management organization to implement the collection taxes and fees for payment of conservation easements and funding operating and maintenance costs. Part of the nature preserve might need reforestation where vital wildlife habitat has been destroyed. Possibly, the cost of reforestation might be defrayed with contributions of donors under the Kyoto Protocol. Given the long accumulation of ambient solid waste in much of Ulcinj’s valuable habitat, a major clean-up will be needed and should be included in the funding for launch of the nature preserve and eco-infrastructure system. From the beginning, park rangers should patrol and enforce rules for sanitation and protection of habitat. Scientific NGOs and government institutes should be charged with continuous monitoring of habitats and species along the ecoinfrastructure system and the preserve. They will also need to monitor the number and nature of ecotourism activities to ensure such are not endangering sensitive habitats and wildlife. Finally, the importance of Ulcinj not only for Montenegro’s emerging ecotourism industry but for the preservation of essential migratory and water fowl habitat makes it necessary that any local economic development in the municipality, including the establishment of exclusive resorts, be harmonized with preservation of its natural assets. Our overall conclusion is that there are international examples of success in creating and operating nature preserves and eco-infrastructure under conditions similar to those found in Ulcinj Municipality. These examples warrant confidence that Ulcinj can likewise achieve this result. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 13 7. References Brewer, Richard. 2003. Conservancy: The Land Trust Movement in America: Who, What, How, Why to Save the Land with Private Initiatives, Plus Trails and Greenways. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. Dömpke, Stephan, Elena Ferretti, and Danka Petrović. 2008. Second Draft Background Study for the establishment of the Bojana Delta Regional Park. BRL Ingénierie, Berlin. Honey, Martha. 2008. Ecotourism and Sustainable Development: Who Owns Paradise? Carruyo, Light. 2007. Producing Knowledge, Protecting Forests, Rural Encounters with Gender, Ecotourism, and International Aid in the Dominican Republic. URS Corporation. 2004. Ellwood-Devereux Coast Open Space and Habitat Management Plan. Goleta, CA: City of Goleta, County of Santa Barbara and University of California, Santa Barbara. The Nature Conservancy. Protecting the Ancient Trees of Chile. http://www.nature.org/success/valdivian.html NEAP Priority Actions Program. Plan for the Protection of Ornithologicaly Important Carp Fishponds in Croatia: Pilot Project. Crna Mlaka. Zagreb: Republic of Croatia. Sustainable Development Sector Management Unit. 2007. Implementation, Completion and Results Report: Costa Rica Ecomarkets Project. Washington, DC: World Bank. Hartshorn, Gary, Paul Ferraro, and Gary Spergel. 2005. Evaluation of the World Bank—GEF Ecomarkets Project in Costa Rica. Washington, DC: The World Bank. The Nature Conservancy. Ecotourism and Conservation Finance: Making Tourism Pay Its Way. http://www.nature.org/aboutus/travel/ecotourism/about/art14824.htm The Nature Conservancy. $24 Million of Guatemala’s Debt Now Slated for Conservation. http://www.nature.org/wherewework/centralamerica/guatemala/work/art19052.html Occhiolini, Michael. 1989. Debt-for-Nature Swaps. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Osborne, David, and Peter Plastrik. 2000. The Reinventor’s Fieldbook: Tools for Transforming Your Government. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 14 The Urban Institute. 2009. Draft Final Design for Eco-Infrastructure in the Bojana Delta, The World Bank’s Montenegro Sustainable Tourism Development Project. Previous version presented at series of public meetings in Montenegro. IDG Working Paper No. 2009-07 15