Hayagreeva Rao on Sarah Soule on MARKET REBELS SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

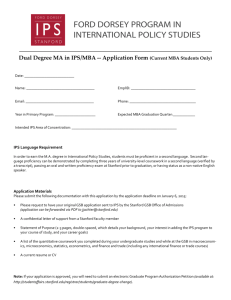

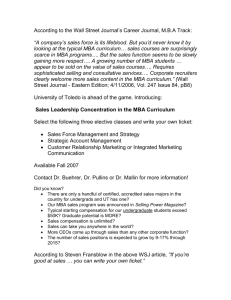

advertisement