Rhabdomyolysis M I N I L E C T U R... R I C H A R D J... P G Y - 2

advertisement

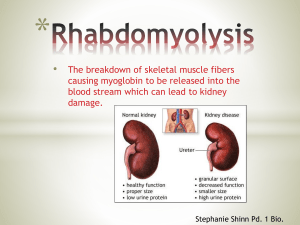

Rhabdomyolysis MINI LECTURE RICHARD JIN PGY-2 2/23/15 Case Presentation 47 y/o M with pmh HTN, ETOH dependency complains of passing out, feeling lethargic, and muscle aches. Upon further questioning the pt admits to doing a large dose of crystal meth and losing consciousness. Vitals: Afebrile, hemodynamically stable. Labs (pertinent): BMP:Creatinine 2.9 (baseline 0.8), potassium 5.1, otherwise normal. CBC: normal Serum CK: 28,000 U/A: Myoglobin present Objectives Identify causes of rhabdomyolysis Describe signs and symptoms How make the diagnosis Mikesgym.org Review medical management strategies for rhabdomyolysis Rhabdomyolysis Breakdown of muscle fibers, specifically of the sarcolemma of skeletal muscle, resulting in release of myoglobin. Released myoglobin may cause acute kidney injury or ultimately renal failure. Shift of extracellular fluid into injured muscles resulting in underperfusion of the kidneys. Rhabdomyolysis Causes (Muscle Breakdown) RHABDOMYOLYSIS Nontraumatic Traumatic/Compression -Multiple Trauma -Crush Injury -Surgery -Coma -Immobilization Exertional -Exertion -Heat illness -Seizures -Metabolic myopathies -Malignant hyperthermia -Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Nonexertional -ETOH -Drugs -Infection -Electrolytes Causes (Metabolic) Clinical Signs and Symptoms “Triad”: Muscle pain, weakness, dark urine Fatigue Joint pain Seizures AKI Compartment syndrome Disseminated intravascular coagulation Laboratory Findings Creatine kinase: >5x ULN (1500-100,000) Rises within 2 to 12 hours following the onset of muscle injury and reaches its maximum within 24 to 72 hours. A decline is usually seen within three to five days of cessation of muscle injury1,2. Myoglobinuria Hyperkalemia Hyperphosphatemia Hypocalcemia Hyperuricemia Diagnosis Elevation in serum creatine kinase (> 5x ULN) + acute neuromuscular illness or dark urine without any other symptoms. Generally not required: Muscle biopsy Electromyography Magnetic resonance imaging Management Treat underlying cause. Early aggressive fluid resuscitation. Electrolyte replacement. Alkalinization of urine? Fasciotomy. Fluid Resuscitation Optimal fluid and rate of repletion are unclear. No studies comparing efficacy/safety of different types and rate of fluid administration. Algorithm CK>5000 Isotonic Saline Titrate IVF -Initial Resuscitation: 1-2 L/hr -100-200 ml/hr (if hemolysis induced injury) -Correct electrolyte abnormalities UOP goal: 200-300ml/hr Serial CK measurements CK<5000 Stop Treatment Bicarbonate Bicarbonate: Forced alkaline diuresis May reduce renal heme toxicity May also decrease the release of free iron from myoglobin, the formation of vasoconstricting F2-isoprostanes, and the risk for tubular precipitation of uric acid3,4 No clear clinical evidence that an alkaline diuresis is more effective than a saline diuresis in preventing AKI5. Mannitol, Dialysis Mannitol: Forced diuresis May minimize intratubular heme pigment deposition and cast formation, and/or by acting as a free radical scavenger, thereby minimizing cell injury6,7. Net clinical benefit of remains uncertain, and, therefore, not routinely administered. Dialysis Use of dialysis to remove myoglobin, hemoglobin, or uric acid in order to prevent the development of renal injury has not been demonstrated8. Back to the Patient Aggressive fluid resuscitation started. Bolused normal saline x 3 Liters in the ED. Maintained on normal saline 200cc/hr with matching urine output of 200cc/hr. Serial CK measurements (8 hrs apart: 28k 33k 38k 30k 24k 18k 5k). After 4 days in the hospital pt’s renal function recovered and was discharged home. Conclusion When rhabdomyolysis is suspected aggressive fluid resuscitation should started to prevent pigment nephropathy. Titrate to UOP 200-300cc/hr. The use of bicarbonate, mannitol, and dialysis: net clinical benefit has not been shown. References 1. Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis -- an overview for clinicians. Crit Care 2005; 9:158. 2. Khan FY. Rhabdomyolysis: a review of the literature. Neth J Med 2009; 67:272. 3. Melli G, Chaudhry V, Cornblath DR. Rhabdomyolysis: an evaluation of 475 hospitalized patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2005; 84:377. 4. Vanholder R, Sever MS, Erek E, Lameire N. Rhabdomyolysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2000; 11:1553. 5. Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE. Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis -- an overview for clinicians. Crit Care 2005; 9:158. 6. Zager RA. Combined mannitol and deferoxamine therapy for myohemoglobinuric renal injury and oxidant tubular stress. Mechanistic and therapeutic implications. J Clin Invest 1992; 90:711. 7. Odeh M. The role of reperfusion-induced injury in the pathogenesis of the crush syndrome. N Engl J Med 1991; 324:1417. 8. Holt S, Moore K. Pathogenesis of renal failure in rhabdomyolysis: the role of myoglobin. Exp Nephrol 2000; 8:72.