EFFECT OF ZINC ADDITION ON THE PROPERTIES OF MAGNESIUM ALLOYS

advertisement

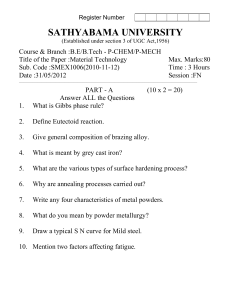

EFFECT OF ZINC ADDITION ON THE PROPERTIES OF MAGNESIUM ALLOYS SAMIR SANI ABDULMALIK A project report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Engineering (Mechanical-Advanced Manufacturing Technology) Faculty of Mechanical Engineering University Technology Malaysia JANUARY 2012 iv To my mother for her tireless prayers To Engr Isyaku Jibrin Sani for his Financial Support v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to say thank you very much to my supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mohd Hasbullah Bin Hj. Idris for his wonderful supervision style and encouragement throughout the project work My special regards also goes to my mother for her tireless prayers, and to Engineer Jibring Isyaku Sani for his tremendous financial support Finally I want to appreciate the effort of all those who have directly or indirectly contributed to the successful completion of this project work, thank you all. vi ABSTRACT Magnesium alloys are currently used in many structural applications. It is believed that magnesium and its alloys may also find applications in biomedical application. In this study, the effects of Zinc (Zn) addition on the properties of magnesium (Mg) alloys, i.e. Mg–xZn (x = 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) were investigated. Optical microscopy, scanning Electron Microscope (SEM), tensile and Vickers hardness testing were used for the characterization and evaluation of the microstructure and mechanical properties of the alloys. Electrochemical corrosion measurement was also employed to determine the corrosion resistance of the alloys. The results show that magnesium alloy with 6 wt. % zinc content (denoted as Mg- 6Zn) shows good corrosion resistance and mechanical properties). vii ABSTRAK Pada masa ini aloi magnesium (Mg) telah digunakan dalam pelbagai aplikasi struktur. Dipercayai bahawa magnesium dan aloinya telah digunakan dalam bidang bioperubatan. Dalam kajian ini, kasan pertambahan zink (Zn) (2, 4, 6, 8 dan 10% berat) tehadap sifat mekanikal dan kakisan aloi magnesium, Mg-xZn telah dikaji. Analisis menggunakan mikroscop optik, Scanning Electron Mikroscopy (SEM),ujian ketegangan dan kekerasan Vickers telah digunakan bagi pencirian dan penilaian mikrostructur dan sifat mekanikal aloi yang dikaji. Ujian kakisan electrokimia juga telah digunakan untuk menilai sifat rintangan kakisan aloi. Keputusan ujikaji menunjukan bahawa aloi magnesium dengan kandungan 6% berat zink (diwakili dengan Mg-6Zn) memberikan sifat kakaisan dan mekanikal yang baik. viii TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 2 TITLE PAGE DECLARATION ii DEDICATION iv ACKNOWLEDGMENT v ABSTRACT vi ABSTRAK vii LIST OF CONTENTS viii LIST OF TABLES xii LIST OF FIGURES xiii LIST OF APPENDICES xv INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Statement of Problem 3 1.3 Objectives 3 1.4 Scopes 4 LITRETURE REVIEW 2.1 Overview of Biomaterials 5 2.1.1 Uses for Biomaterials 6 ix 2.1.1.1 Orthopedics 6 2.1.1.2 Cardiovascular Applications 7 2.1.1.3 Ophthalmic 7 2.1.1.4 Dental Applications 7 2.1.2 Types of Biomaterials 2.1.2.1 Metallic materials 8 2.1.2.2 Polymers 9 2.1.2.3 Ceramics 9 2.1.2.4 Composites 10 2.1.3 Natural Biomaterials 11 2.1.4 Application of Biomaterials 11 2.2 Natural Bone 2.2.1 Desirable Properties of Artificial Bone Material 12 13 2.2.1.1 Body Condition 13 2.2.1.2 Mechanical Properties 15 2.2.1.3 Corrosion Resistance 15 2.3 Conventional Metallic Materials Used For Medical Devices 2.4 7 16 2.3.1 Stainless steels 17 2.3.2 Cobalt-Base Alloys 17 2.3.3 Titanium and Titanium-Base Alloys 18 Magnesium 18 2.4.1 Properties of Pure Magnesium 19 2.4.2 Melting and casting of magnesium 20 2.4.2.1 Melting 20 x 2.4.3 2.5 2.6 3 2.4.2.2 Casting and working of magnesium 22 Magnesium Alloys 22 2.4.3.1 Common Alloying Elements 23 2.4.3.1.1 Aluminum 23 2.4.3.1.2 Calcium 23 2.4.3.1.3 Manganese 23 2.4.3.1.4 Rare Earths 24 2.4.3.1.5 Zinc 24 Zinc Metal 24 2.5.1 Zinc Biological role 24 Researched Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys 25 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction 28 3.2 Research Design 30 3.2.1 30 Casting 3.2.2. Microstructural Characterization 33 3.2.3 Hardness Test 35 3.2.4 Tensile Test 37 3.2.5 Electrochemical Measurement 4 38 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Selection of optimum zinc addition 39 4.1.1 Nominal Composition Analysis 39 xi 4.1.2 Microstructural Characterization 4.1.3 Hardness Test 43 4.1.4 44 Tensile Test 4.1.5 Corrosion Electrochemical Test 5 40 CONCLUSION 46 47 REFERENCES 48 APENDIX A-C 51 xii LIST OF TABLES TABLE NO. TITLE PAGE 2.1 Example of Medical and Dental Material and their Applications 2.2 Example of Polymers used as Biomaterials 2.3 Example of Biomaterial Ceramics 2.4 Summary of the mechanical properties and porosity of human bone 2.5 Raw Materials for Magnesium Production 4.1 Nominal chemical composition of the Mg-Zn alloys 4.2 The Tensile strength, Yield, and Elastic Modulus value for Mg-Zn alloys 8 9 10 15 19 39 45 xiii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE NO. TITLE PAGE 2.1 Implant material requirements in orthopedic applications 6 2.2 Hip joint replacement 12 2.3 Details of the bone structure 13 2.4 Closed packed structure of pure magnesium 20 3.1 Flowchart showing the summary of research methodology 29 3.2 (a) Magnesium Ingot (b) Pure Zinc 30 3.3 (a) Mg-Zn Melting, (b) Pouring into steel mold, (c) Designed Mold, (e) cast sample (f) the mold used 3.4 (a) Olympus BX60, (b) Philips XL 40, (c) Supra 35VP, used for the characterization of the microstructure 3.5 37 Electrochemical test (Parstat-2263) set up used for the corrosion Measurement 4.1 36 Instron universal tensile testing machine used in the tensile testing of the samples 3.7 34 (a) Matsuzawa DVK-2 used for the hardness testing (b) location of the test on the sample 3.6 31 38 Microstructure of the as cast (a) pure magnesium, (b) Mg-2Zn, (c) Mg-4Zn, (d) Mg-6Zn, (e) Mg-8Zn, (f) Mg-10Zn 40 xiv 4.2 FE-SEM micrographs of (a) Mg-8Zn alloy, (b) Mg-10Zn Alloy, (c) (Mg, Zn)-containing phase in the grain, (d) (mg, Zn)-containing phase at the grain boundary 4.3 EDS analysis of the secondary phases (a) on the grain, (b) at the grain boundary 4.4 43 The Tensile strength value of Mg-Zn alloys as a function of zinc addition. 4.6 42 The hardness value of Mg-Zn alloys as a function of zinc addition 4.5 41 45 Electrochemical polarization curves of Mg-Zn alloys under investigation 46 xv LIST OF APPENDICES APPENDIX TITLE PAGE A Compositional Analysis of the as- cast Samples 51 B The Stress/Strain Graphs for the alloys Samples 61 C Polarization Curves of the Samples 66 1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Biomaterial implants are used as a replacement of a bone part or as a support in the healing process. Replacement of a bone part requires implants to stay in the body permanently, while support only requires that the implant remain in the body for a shorter period. When permanent implant is used for a temporary application, additional surgeries are required to remove these devices after the healing process. Thus, removal process increases the patient grim and cost of health care. In contrast, biodegradable materials require no additional surgeries for removal as they dissolve after the healing process is complete. This also eliminates the complications associated with the longterm presence of implants in the body. Finally, after these materials degrade within the body, it is important that the body can metabolized the degradation products, and thus are bioabsorbable. The first materials to be used as commercial biodegradable and bioabsorbable implant materials were polymers. The most commonly and earliest used absorbable materials include polyglycolic acid (PGA), poly-lactic acid (PLA), and poly-dioxanone (PDS). However, low mechanical properties and radiolucency are the limitation with these materials. Applications of polymeric materials in load-bearing and tissue 2 supporting applications is severely restricts due to low strength, because the mechanical needs of the body required a greater amount of material. Metals due to their relatively high strength and fracture toughness possesses desirable mechanical properties, however, most of the metals are biologically toxic. Studies revealed that conventional implant, like cobalt, stainless, chromium, and nickelbased alloys produce corrosion products, which are harmful to the human body [1] [2] [3] [4]. Magnesium and its alloys are biodegradable metals and exhibit improved mechanical properties and corrosion resistance. However most of the reported biomedical magnesium alloys contain aluminum and/or rare earth (RE) elements. It is well known that Al and rare earth elements are harmful to neurons, osteoblasts, and also associated with dementia and could lead to hepatotoxicity. Consequently, Al and RE are unsuitable alloying elements for biomedical magnesium materials, particularly when they are above certain levels [5] Pure magnesium was indicated as suitable candidate for temporary implant; however, the major drawback of Mg is its low corrosion resistance which results to low mechanical strength in the physiological environment. Alloying elements can be added to increase the strength of pure Mg but alloying elements should be selected carefully to maintain the Mg’s biocompatibility. With the purpose of searching for suitable alloying elements for biomedical magnesium alloys, researchers demonstrated that Calcium (Ca), Manganese (Mn), and Zinc (Zn) could be appropriate candidates. Zinc is one of the essential elements in human body that also provide mechanical strengthening in Mg-based alloys. Zinc can improve the corrosion resistance and mechanical properties of magnesium alloys, Zinc additions increase the strength of Mg-based alloys primarily through precipitation strengthening. Furthermore, zinc is one of the most abundant 3 nutritionally essential elements in the human body, and has basic safety for biomedical applications [6] [7]. 1.2 Statement of Problem The mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of magnesium alloys must be sufficiently investigated for medical application. Magnesium is essential to human metabolic functions and is the fourth most abundant cation in human body. In vitro cytotoxicity of pure magnesium metal showed positive cell proliferation and viability with no sign of growth inhibition. The fracture toughness of magnesium is greater than that of ceramics, but pure magnesium corrodes too quickly in the physiological environment (pH 7.4–7.6), losing mechanical integrity before tissue healing. In an effort to maintain the mechanical integrity, and biocompatibility, more alloying compositions are necessary. 1.3 Objectives The objectives of this project are: 1. To establish optimum material composition Mg-Zn 2. To establish the effect of Zinc addition on the properties of Mg alloy as biodegradable material 4 1.4 Scopes This project was conducted within the following boundaries: 1. Mg-Zn alloys was prepared and cast using gravity die casting process 2. The effect of zinc addition was characterized and measured through: (a) Microstructure observation (b) Mechanical properties test, and (c) Electrochemical corrosion tests 5 CHAPTER 2 LITRATURE REVIEW 2.1 Overview of Biomaterials A biomaterial is any synthetic material that is used to replace or restore function to a body tissue and is continuously or intermittently in contact with body fluids. Exposure to body fluids usually implies that the biomaterial is placed within the interior of the body, and this places several strict restrictions on materials that can be used as a biomaterial [8]. Biomaterial must be biocompatible; it should not elicit an adverse response from the body, and vice versa. Additionally, it should be nontoxic and noncarcinogenic. These requirements eliminate many engineering materials that are available. Next, the biomaterial should possess adequate physical and mechanical properties to serve as augmentation or replacement of body tissues. For practical use, a biomaterial should be amenable to being formed or machined into different shapes, have relatively low cost, and be readily available. Various material requirements that must be met for successful total joint replacement are listed in Figure 2.1 [9]. 6 Figure 2.1: Implant material requirements in orthopedic applications. [9] 2.1.1 Uses for Biomaterials Biomaterials are primarily used to replace hard or soft tissues that have become destroyed or damaged through some pathological process. As a result of these circumstances, it may be possible to remove the damaged tissue and replace it with some suitable synthetic material [10]. Listed below are some common uses of biomaterials. 2.1.1.1 Orthopedics Orthopedic implant devices are one of the most prominent application areas for biomaterials. It has been possible to replace joints, such as the hip, knee, shoulder, ankle, and elbow, and the pains resulted can be considerable, since the introduction of anesthesia, antisepsis, and antibiotics. The relief of pain and restoration of mobility is well known to hundreds of thousands of patients. 7 2.1.1.2 Cardiovascular Applications Problems arose with heart valves and arteries can be successfully treated with implants. The heart valves sometimes fails to either fully opening or fully closing, meaning to say the valve is affected with disease, the diseased valve can be replaced with a variety of substitutes. 2.1.1.3 Ophthalmic The tissues of the eye suffer from several diseases, leading to reduced vision and eventually, blindness. Cataracts, for example, cause cloudiness of the lens. This may be replaced with a synthetic (polymer). As with intraocular lenses, biomaterials are used to preserve and restore vision 2.1.1.4 Dental Applications Within the mouth, both the tooth and supporting gum tissues can be readily destroyed by bacterially controlled diseases. Teeth in their entirety and segments of teeth both can be replaced and restored by a variety of materials. 2.1.2 Types of Biomaterials In general, synthetic biomaterials used for implants can be categorized as: metals, polymers, ceramics, and composites [8] 8 2.1.2.1 Metallic materials Metallic materials are the most widely used for load-bearing implants. For instance, some of the most common orthopedic surgeries involve the implantation of metallic implants. These range from simple wires and screws to fracture fixation plates and total joint prostheses (artificial joints) for hips, knees, shoulders, ankles, and so on. In addition to orthopedics, metallic implants are used in maxillofacial surgery, cardiovascular surgery, and as dental materials. Although many metals and alloys are used for medical device applications, the most commonly employed are stainless steels, commercially pure titanium and titanium alloys, and cobalt-base alloys (Table 2.1). Table 2.1: Example of Medical and Dental Material and their Applications 9 2.1.2.2 Polymers Polymers are used in medicine as biomaterials. Their applications range from facial prostheses to tracheal tubes, from kidney and liver parts to heart components, and from dentures to hip and knee joints. Polymeric materials are also used for medical adhesives and sealants and for coatings that serve a variety of functions. Example of polymer material is shown in Table 2.2. Table 2.2: Example of Polymers used as Biomaterials 2.1.2.3 Ceramics Traditionally, ceramics have seen widescale use as restorative materials in dentistry. These include materials for crowns, cements, and dentures. However, their use in other fields of biomedicine has not been as extensive, compared to metals and polymers. For example, the poor fracture toughness of ceramics severely limits their use for load-bearing applications. Some ceramic materials are used for joint replacement and bone repair and augmentation as shown in the Table 2.3. 10 Table 2.3: Example of Biomaterial Ceramics Ceramics and glasses Applications Alumina Join replacement, dental implants Zirconia Join replacement Calcium phosphate Bone repair and augmentation, surface coatings on metals Bioactive glasses Bone replacement Porcelain Dental restoration Carbons Heart valves, percutaneous devices, dental implants 2.1.2.4 Composites Composites biomaterials are used in the field of dentistry as restorative materials or dental cements. Although carbon-carbon and carbonreinforced polymer composites are of great interest for bone repair and joint replacement because of their low elastic modulus levels, these materials have not displayed a combination of mechanical and biological properties appropriate to these applications. Composite materials are, however, used extensively for prosthetic limbs, where their combination of low density/weight and high strength make them ideal materials for such applications. 11 2.1.3 Natural Biomaterials One of the advantages of using natural materials for implants is that they are similar to materials familiar to the body. Natural materials do not usually offer the problems of toxicity often faced by synthetic materials. Also, they may carry specific protein binding sites and other biochemical signals that may assist in tissue healing or integration. The problem with the natural materials is that they can be subjected to immunogenicity, and their tendency to denature or decompose at temperatures below their melting points. This severely limits their fabrication into implants of different sizes and shapes. An example of a natural material is collagen, which exists mostly in fibril form, has a characteristic triple-helix structure, and is the most prevalent protein in the animal world [8]. 2.1.4 Application of Biomaterials Total joint replacement is widely regarded as the major achievement in orthopedic surgery in the 20th century. Arthroplasty, or the creation of a new joint, is the name given to the surgical treatment of degenerate joints aimed at the relief of pain and the restoration of movement. This has been achieved by excision, interposition, and replacement arthroplasty and by techniques that have been developed over approximately 180 years. Hip arthroplasty generally requires that the upper femur (thigh bone) be replaced and the mating pelvis (hip bone) area be replaced or resurfaced. As shown in Figure 3, a typical hip prosthesis consists of the femoral stem, a femoral ball, and a polymeric (ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene, or (UHMWPE)) socket (cup) with or without a metallic backing [9]. 12 Figure 2.2: Hip joint replacement 2.2 Natural Bone Bone is a composite type substance containing calcium, phosphate, magnesium and collagen. Structurally bone is divided into five parts, namely: 1. Periostium 2. Compact bone 3. Spongy bone 4. Bone marrow, and 5. Epiphyseal plate Bones are rigid and elastic in nature. Major percent of the bone is hydroxyapatite and another small percent of carbonate is present in human bone. 13 Figure 2.3: Details of the bone structure [11] Mineral substances in the bone like calcium, phosphate and magnesium make the bone as rigid substance and collagen makes it as elastic substance. During bone development stage mineral substance are converted into apatite minerals from crystallographicall amorphous [11] [12]. 2.2.1 Desirable Properties of Artificial Bone Material 2.2.1.1 Body Condition Temperature conditions are not extreme for the materials used, body temperatures being a little less than 38°C (98.6°F). However, the chemical physiological environment and biomechanical environment can be extreme. For structural implants used to repair the hip, it is estimated that the average nonactive person may place 1 to 14 2.5 × 106 cycles of stress on his or her hip in a year. For a person 20 to 30 years of age, with a life expectancy of 70 to 80 years, that is the equivalent of approximately 108 cycles of loading in a lifetime. The actual loads and cycles are a function of the weight and activity level of the person, but the need for longtime cyclic capability in fatigue is obvious. Other applications in the body also impart many millions of fatigue cycles to the device or component implanted. In considering the parameters of materials for intracorporeal applications, several factors are of major importance. It is generally agreed that the material must: i. Be nontoxic and noncarcinogenic, cause little or no foreign-body reaction, and be chemically stable and corrosion resistant. This is known as biocompatibility. ii. Be able to endure large and variable stresses in the highly corrosive environment of the human body iii. Be able to be fabricated into intricate shapes and sizes Many structural applications of materials in the body require that the replacement material fit into a space perhaps only one-fourth the area of the part being permanently or temporarily replaced or assisted. Consequently, the implant may have to withstand loads up to 16 or more times that which the human bone must withstand. In restorative dentistry, high compressive biting forces are combined with large temperature changes and acidity to produce a challenging environment. It is clear that there can be very great mechanical loading demands on biomaterials used for structural purposes [13] 15 2.2.1.2 Mechanical Properties Mechanical properties of artificial bone material should be similar to the natural bone. Rejection of artificial implants due to mismatch in mechanical property between natural bone and implant is known as biomechanical incompatibility. Important mechanical properties are tensile strength, hardness and modulus of elasticity. Artificial bone material considered for implant should have high strength and low modulus of elasticity to match the property of natural bone [14]. Table 2.4: Summary of the mechanical properties and porosity of human bone [14] Bone Cortical Bone Cancellous bone Compressive Strength (MPa) 130-180 Flexural Strength (MPa) 135-193 Tensile Strength (MPa) 50-150 Modulus (MPa) Porosity (%) 12-18 5-13 4-12 NA (Not 1-5 0.1-0.5 30-90 available 2.2.1.3 Corrosion Resistance Corrosion has been a major determining factor in the selection of materials for use in the body environment. The first requirement for any material whether a metal/alloy, ceramic, or polymer to be placed in the body is that it should be biocompatible and not cause any adverse reaction in the body. The material must withstand the body environment and not degrade to the point that it cannot function in the body as intended. For example, metals used in the cardiovascular system must be nonthrombogenic, and, in general, the more electronegative the metal with respect to blood, the less thrombogenic the metal will be. For a material to be considered resistant 16 to corrosion in the body, its general corrosion rate usually must be less than, 0.01 mil/yr (0.00025 mm/yr). In vitro electrochemical measurements can be conducted in controlled environments, and these techniques provide methods of determining the basic corrosion reactions necessary for predicting the corrosion behavior of materials and for screening and characterizing materials intended for use in surgical applications [15]. 2.3 Conventional Metallic Materials Used For Medical Devices Metals have been successfully used as biomaterials for many years. Besides orthopedics, there are other markets for metallic implants and devices, including oral and maxillofacial surgery (e.g., dental implants, craniofacial plates and screws) and cardiovascular surgery (e.g., parts of pacemakers, defibrillators, and artificial hearts; balloon catheters; valve replacements; stents; and aneurysm clips). Surgical instruments, dental instruments, needles, staples, and implantable drug pump housings are also made from metallic materials. For structural applications in the body (e.g., implants for hip, knee, ankle, shoulder, wrist, finger, or toe joints), the principal metals are stainless steels, cobalt-base alloys, and titanium-base alloys. These metals are popular primarily because of their ability to bear significant loads, withstand fatigue loading, and undergo plastic deformation prior to failure. Other metals and alloys employed in implantable devices include commercially pure titanium (CP-Ti), shape memory alloys (alloys based on the nickel-titanium binary system), zirconium alloys, tantalum (and, to a lesser extent, niobium), and precious metals and alloys [16]. 17 2.3.1 Stainless steels Stainless steels are iron-base alloys that contain a minimum of 10.5% Cr, the amount needed to prevent the formation of rust in unpolluted atmospheres. Stainless steels used for implants are suitable for close and prolonged contact with human tissue (i.e., warm, saline conditions). Specific requirements for resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion and the quantity and size of nonmetallic inclusions apply to implant-grade stainless steels. Austenitic stainless steels are popular for implant applications because they are relatively inexpensive, they can be formed with common techniques, and their mechanical properties can be controlled over a wide range for optimal strength and ductility. Stainless steels for implants are wrought alloys (i.e., they are fabricated by forging and machining). Austenitic stainless steels are not sufficiently corrosion resistant for long-term use as an implant material. They find use as bone screws, bone plates, intramedullary nails and rods, and other temporary fixation devices. Recently, other stainless steels ‘nitrogen-strengthening stainless steel’ has been developed and standardized that have increased corrosion resistance and improved mechanical properties. Nitrogen-strengthened alloys are being used for bone plates, bone screws, spinal fixation components, and other medical components. Nitrogenstrengthened stainless steels have better crevice and pitting corrosion resistance. 2.3.2 Cobalt-Base Alloys Cobalt-base alloys were first used in the 1930s. The Co-Cr-Mo alloy Vitallium was used as a cast dental alloy and then adopted to orthopedic applications starting in the 1940s. The corrosion of cobalt-chromium alloys is more than an order of magnitude greater than that of stainless steels, and they possess high mechanical property 18 capability. Although cobalt alloys were first used as cast components, wrought alloys later came into use. 2.3.3 Titanium and Titanium-Base Alloys Titanium and its alloys used for implant devices have been designed to have excellent biocompatibility, with little or no reaction with tissue surrounding the implant. Titanium derives it corrosion resistance from the stable oxide film that forms on its surface, which can reform at body temperatures and in physiological fluids if damaged. Increased use of titanium alloys as biomaterials is occurring due to their lower modulus, superior biocompatibility, and enhanced corrosion resistance when compared to more conventional stainless steels and cobaltbase alloys. 2.4 Magnesium Magnesium always appears in nature in ionic form with the following electron arrangement: 1S22S22P63S2.This arrangement is characterized by the low ionization energies relative to the two most external electrons, which are at the 3S level. The low standard reduction potential of magnesium is the reason why no metallic magnesium is found in nature: Mg2+ + 2e– = Mg E0 = –2.375 V The raw materials for the production of magnesium come from different magnesium sources. In all cases they will be accompanied by additional materials, depending on their source. 19 Table 2.5: Raw Materials for Magnesium Production Material Chemical formula Magnsite MgCO3 Dolomite MgCO3·CaCO3 Bischofite MgCL2·6H2O Carnallite MgCL2·KCL·6H2O Serpentine 3MgO·2SiO2·2H2O Sea water Mg2+(aq) 2.4.1 Properties of Pure Magnesium Magnesium is classified as an alkaline earth metal. It is found in Group 3 of the periodic table, and has the atomic properties as: i. Element Symbol Mg ii. Atomic Number 12 iii. Atomic Weight 24.3050 iv. Atomic Diameter 0.320 nm v. Atomic Volume 14.0 cm3/mol Lattice parameters of pure magnesium estimated at room temperature are: a = 0.32092 nm and c = 0.52105 nm. The c/a ratio is 1.6236 which is close to the ideal value of 1.633. Therefore, magnesium is considered as perfectly closed packed [17]. 20 Figure 2.4: Closed packed structure of pure magnesium The density of magnesium at 20°C is 1.738 g/cm3.At the melting point of 650°C reduced to 1.65 g/cm3, on melting there is an expansion in volume of 4.2%. At higher temperature volume diffusion is very important, especially at T > 0.6 T m, where Tm is the absolute melting point. At lower temperatures pipe diffusion, i.e., diffusion along dislocation cores, may become more significant. Grain boundary diffusion plays a role in polycrystals because the grain boundary acts as a low energy channel for the movement of atoms. The thermal conductivity of pure magnesium measured at elevated temperatures decreases with increasing temperature. At very low temperatures the thermal conductivity exhibits high values [17] 2.4.2 Melting and casting of magnesium 2.4.2.1 Melting It is usual for magnesium to be melted in mild steel crucibles for both the alloying and refining or cleaning stages before producing cast or wrought components. 21 Unlike aluminium and its alloys, the presence of an oxide film on molten magnesium does not protect the metal from further oxidation. On the contrary, it accelerates this process. Melting is complete at or below 650 °C and the rate of oxidation of the molten metal surface increases rapidly with rise in temperature such that, above 850 °C, a freshly exposed surface spontaneously bursts into flame. Consequently, suitable fluxes or inert atmospheres must be used when handling molten magnesium and its alloys. For many years, thinly fluid salt fluxes were used to protect molten magnesium which were mixtures of chlorides such as MgCl2 with KCl or NaCl. However, the presence of the chlorides often led to problems with corrosion when the cast alloys were used in service [19]. Cover gases (e.g. SO2 or argon), or a mixture of an active gas diluted with CO2, N2, replaced the used of the salt, also sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) was widely accepted as the active gas because it is non-toxic, odourless, colourless, and effective at low concentrations. But the disadvantage of sulphur hexafluoride SF6 is, however, relatively expensive, and is now realised to be a particularly potent greenhouse gas with a socalled Global Warming Potential (GWP) of 22, 000 to 23, 000 on a 100 year time horizon. As a result of that efforts are therefore being made to find other active gases containing fluorine and one promising alternative is the organic compound HFC 134a (1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) that is readily available worldwide because of its use as a refrigerant gas. It is also less expensive than SF6. HFC 134a has a GWP of only 1600, and an estimated atmospheric lifetime of 13.6 years compared with 3, 200 years for SF6. Moreover less is consumed on a daily basis so that the overall potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is predicted to be 97% [19]. 22 2.4.2.2 Casting and working of magnesium Most magnesium components are now produced by high-pressure die casting machine. Cold chamber machines are used for the largest castings and molten shot weights of 10 kg or more can now be injected in less than 100 ms at pressures that may be as high as 1500 bar. Hot chamber machines are used for most applications and are more competitive for smaller sizes due to the shorter cycle times that are obtainable. A reported disadvantage with high pressure die castings is that they may contain relatively high levels of porosity. This restricts opportunities for using heat treatment to improve their properties because exposure to high temperatures may cause the pores to swell and form surface blisters. Sand castings and low pressure permanent mould castings generally contain less porosity and are used to produce components having more complicated shapes. They can then be heat treated if the alloys respond to age hardening. With permanent mould casting, turbulence can be minimized by introducing the molten metal into the bottom of the mould cavity, under a controlled pressure, thereby allowing unidirectional filling of the mould [19]. 2.4.3 Magnesium Alloys Magnesium is readily available commercially with purities exceeding 99.8% but it is rarely used for engineering applications without being alloyed with other metals. The fact that its atomic diameter (0.320 nm) is such that it enjoys favourable size factors with a diverse range of solute elements. 23 2.4.3.1 Common Alloying Elements 2.4.3.1.1 Aluminum Aluminum is the most commonly used alloying element, and the maximum solubility is 11.5 at % (12.7 mass %) and alloys in excess of 6 mass % can be heat treated. Aluminum improves strength, the optimum combination of strength and ductility being observed at about 6%.Alloys is readily castable. 2.4.3.1.2 Calcium Alloying with calcium is becoming more common in the development of cheap creep resistant alloys. Ca can act as deoxidant in the melt or in subsequent heat treatment. It improves the roll ability of sheet but >0.3 mass % can reduce the weld ability. 2.4.3.1.3 Manganese Manganese is usually not employed alone but with other elements, e.g., Al. It reduces the solubility of iron and produces relatively innocuous compounds. It increases the yield strength and improves salt water corrosion resistance of Mg-Al and Mg-Al-Zn alloys. Binary alloys (M1A) are used in forgings or extruded bars. The maximum amount of manganese is 1.5–2 mass %. 24 2.4.3.1.4 Rare Earths Rare Earths are added to magnesium alloys to improve the high temperature strength, and creep resistance; they are usually added as Mischmetal. 2.4.3.1.5 Zinc Zinc is one of the commonest alloying additions. It is used in conjunction with Al (e.g., AZ91 or with zirconium, thorium or rare earths) [18]. 2.5 Zinc Metal Zinc is, in some respects, chemically similar to magnesium, because its ion is of similar size and its only common oxidation state is +2. Zinc is the 24th most abundant element in the Earth's crust and has five stable isotopes [19]. 2.5.1 Zinc Biological role Zinc is an essential trace element, necessary for plants, animals, and microorganisms. Zinc is found in nearly 100 specific enzymes (other sources say 300), serves as structural ions in transcription factors and is stored and transferred in metallothioneins. It is "typically the second most abundant transition metal in organisms" after iron and it is the only metal which appears in all enzyme classes. In proteins, Zn ions are often coordinated to the amino acid side chains of aspartic acid, glutamic acid, cysteine and histidine. The theoretical and computational 25 description of this zinc binding in proteins (as well as that of other transition metals) is difficult. There are 2–4 grams of zinc distributed throughout the human body. Most zinc is in the brain, muscle, bones, kidney, and liver, with the highest concentrations in the prostate and parts of the eye. Semen is particularly rich in zinc, which is a key factor in prostate gland function and reproductive organ growth. In humans, zinc plays "ubiquitous biological roles". It interacts with "a wide range of organic ligands", and has roles in the metabolism of RNA and DNA, signal transduction, and gene expression. It also regulates apoptosis. A 2006 study estimated that about 10% of human proteins potentially bind zinc, in addition to hundreds which transport and traffic zinc; a similar in silico study in the plant Arabidopsis thaliana found 2367 zinc-related proteins [21]. In the brain, zinc is stored in specific synaptic vesicles by glutamatergic neurons and can "modulate brain excitability". It plays a key role in synaptic plasticity and so in learning. However it has been called "the brain's dark horse" since it also can be a neurotoxin, suggesting zinc homeostasis plays a critical role in normal functioning of the brain and central nervous system [21]. 2.6 Researched Biodegradable Magnesium Alloys For the purpose of searching for suitable alloying elements for biomedical magnesium alloys, researchers exploited the in vivo and the in vitro behavior of magnesium alloys. Yizao Wan [22] in his research work named preparation and characterization of a new biomedical magnesium–calcium alloy. Demonstrated that 0.6 wt % calcium content improved corrosion and mechanical properties of magnesium and the alloy Mg0.6Ca shows good potential as a new biomedical material. Hui Du [23] researched on the effects of the addition of Zn element on the properties of Mg–3Ca. He pointed out that the element Zn could improve both tensile 26 strength and elongation of Mg–3Ca alloys, and attributed that the presence of Ca2Mg6Zn3 phase found in the alloy mainly contributes to these improvement. Jun Wang [24] investigates the Microstructure and corrosion properties of as sub-rapid solidification of Mg–Zn–Y–Nd alloy in dynamic simulated body fluid for vascular stent application. The research shows that as sub-rapid solidification can improve the corrosion resistance of Mg–Zn–Y–Nd alloy in dynamic SBF due to grain refinement. Yuncang Li [25] exploded the effects of calcium (Ca) and yttrium (Y) on the microstructure, mechanical properties, corrosion behavior and biocompatibility of magnesium (Mg) alloys. Results of the investigation indicated that Ca content can enhances the compressive strength, elastic modulus and hardness of the Mg–Ca alloys, but deteriorates the ductility, corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of the Mg–Ca alloys. Also revealed that yttrium addition increases ductility; but decreases the compressive strength, hardness, corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of the alloy Mg–1Ca–1Y. Erlin Zhang [26] research on the in vivo degradation of magnesium alloy implant highlighted that rapid degradation of magnesium implant was observed in the marrow channel than in the cortical bone. Also shown that the degradation of the magnesium implant in the blood caused little change to blood composition but no disorder to liver or kidneys E. Aghion G. Levy [27] evaluated the effect of 0.4% Ca on the in vitro corrosion behavior of Mg–1.2% Nd–0.5% Y–0.5% Zr in a simulated physiological environment. He outlined that 0.4% Ca has a beneficial effect on the corrosion resistance of the tested alloy, and attributed this to the effect of calcium, which reduces oxidation in the molten condition and consequently improves the soundness of the obtained casting, E. Aghion result also shown that the addition of calcium has a damaging effect on the stress corrosion behavior in terms of reduced ultimate tensile strength and 27 ductility of the alloy, and this was mainly due to the embrittlement effect of calcium that was generated by the formation and distribution of Mg2Ca phase at grain boundaries. Zijian Li [28] in his work, research on the development of binary Mg-Ca alloys for use as biodegradable materials reveals that controlled calcium content and processing treatment can lead to the improvement in tensile strength and corrosion properties of the alloy. Also highlighted that Mg-1Ca alloy show an acceptable biocompatibility as a new kind of biodegradable implant material. Yingwei Song [29] explores the in vitro corrosion behaviors of the biodegradable AZ31 in simulated body fluid (SBF), pointing out that some protective film layer was formed on the surface of AZ31 and had perfect biocompatibility. X.N. GU [30] investigates the Corrosion fatigue behaviors of two biomedical Mg alloys AZ91D and WE43 – In simulated body fluid. Demonstrated that die-cast AZ91D alloy indicated a lower fatigue limit than that observed for extruded WE43 alloy . Yin Dongsong [31] demonstrated that Zinc content (3% wt) refined the microstructure, and improved the mechanical properties of Mg-Mn alloy. Shaoxiang Zhang [32] explored in vitro and in vivo potentials of Mg-Zn alloy and point out the alloy shown suitable mechanical properties for implant application and also good corrosion resistance. 28 CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 3.1 Introduction The experimental work in this project was to prepare the magnesium zinc alloys and to study the effect of zinc addition on the microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of Mg-Zn alloys. Figure 3.1.shown the general flowchart of the experimental procedures. 29 Start Prepare Mg-Zn Prepare mold Gravity die mold Melting at 7000C7500C in mild steel crucible Cast at 7300C into steel mold Microstructure characterization Mechanical Test Tensile/Hardness test Result/Discussion Stop Figure 3.1: Flowchart showing the summary of research methodology 30 3.2 Research Design 3.2.1 Casting Pure magnesium ingot (99.99 wt %) Figure 3.2(a) and, pure zinc ingot (99.995 wt. %), Figure 3.2(b), were used in this experiment. Melting process was carried out in a high frequency induction furnace (inductothem) Figure 3.3a using a mild steel crucible under the argon gas atmosphere. After magnesium metal was melted at about 6500C, pure zinc ingot was added. After all these materials were melted completely and superheat to around 7500C, the melt was then cast into a steel mold at 7300C Figure 3.3b. Figure 3.3(c, d and e) shows the schematic mold design, as cast sample, and the original mold used in the casting process. (a) (b) Figure 3.2: (a) Magnesium Ingot (b) Pure Zinc 31 (a) (b) 32 (c) (d) 33 Figure 3.3: (a) Mg-Zn Melting, (b) Pouring into steel mold, (c) Designed Mold, (e) Cast Sample, (f) the mold used 3.2.2. Microstructural Characterization Characterization of the microstructure and phases of the Mg-Zn alloys was conducted using optical microscope (Olympus BX60) and scanning electron microscope (Philips XL 40) equipped with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS). And carls zeiss supra 35VP (FE-SEM), Shown in figure 3.4. 34 (a) (b) 35 (c) Figure 3.4: (a) Olympus BX60, (b) Philips XL 40, (c) Supra 35VP, used for the characterization of the microstructure 3.2.3 Hardness Test The Vickers hardness tests were performed using Matsuzawa DVK-2 material testing machine, at five different locations of the samples according to ASTM-E98-82 standard, Figure 3.5 36 (a) (b) Figure 3.5: (a) Matsuzawa DVK-2 used for the hardness testing (b) location of the test on the sample 37 3.2.4 Tensile Test: The tests were conducted according to ASTM-A370 on an instron universal testing machine with a tensile speed of 1 mm/min. The test sample has a gauge length of 25mm and thickness of 10mm. Extensometer was used to measure the elongation. Data presented in this report were average value of 4 separated measurements. Figure 3.6: Instron universal tensile testing machine used in the tensile testing of the samples 38 3.2.5 Electrochemical Measurement: The electrochemical test ware performed using a (Parstat-2263) test set up. A saturated calomel electrode (KCL) and graphite electrode were used as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively. Samples (working electrode) with a cross section of 1 cm2 was used, all the polarization curves were measured at a scan rate of 0.9 mV/s. Figure 3.7: Electrochemical test (Parstat-2263) set up used for the corrosion measurement 39 CHAPTER 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 4.1 Selection of Optimum Zinc addition 4.1.1 Nominal Composition Analysis Chemical composition as-cast samples were determined by Energy Dispersive Spectrometer (EDS) detector attached to Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), as shown in Table 4.1. Table 4.1: Nominal chemical composition of the Mg-Zn alloys (wt. %) Composition Zn Mg Balance Sample 1 Sample 2 Sample 3 Sample 4 Sample 5 1.62 4.03 6.33 8.46 9.65 98.38 95.97 93.67 91.54 90.35 100 100 100 100 100 40 4.1.2 Microstructural Characterization Optical microstructures of as cast Mg–Zn alloys were shown in figure 4.1. All materials show nearly equiaxed grain structure. However, differences are noted among these samples. Small and separated precipitates are observed within grains for alloys and the width of the grain boundary becomes thicker as the content of zinc increases. In addition, the grain boundaries are characterized by a discontinuous distribution of small precipitates. Figure 4.1: Microstructure of the as cast (a) pure magnesium, (b) Mg-2Zn, (c) Mg-4Zn, (d) Mg-6Zn, (e) Mg-8Zn, (f) Mg-10Zn 41 In trying to point out what the precipitation in Figure 4.1(e) and (f) constitutes of, Figure 4.2(a) and (b) show the FE-SEM micrographs of Mg-8Zn, and Mg-10Zn alloys respectively, and the EDS analysis conducted on the precipitation along the grain and the grain boundary indicates that it is rich in zinc and small amount of magnesium Figure 4.3(a) and (b) suggesting that the precipitation consist of zinc and magnesium. Fine second phases with size of 1-2 μm can be seen in the Mg-Zn alloy in the grain and in the grain boundary of the alloy Figure 4.2(c) and (d). Figure 4.2: FE-SEM micrographs of (a) Mg-8Zn alloy, (b) Mg-10Zn Alloy, (c) (Mg, Zn)-containing phase in the grain, (d) (mg, Zn)-containing phase at the grain boundary 42 Figure 4.3: EDS analysis of the secondary phases (a) on the grain, (b) at the grain boundary 43 4.1.3 Hardness Test With respect to pure magnesium in figure 4.4 the Vickers hardness values of Mg xZn (2, 4, and 6) as a function of the %wt Zn follow an increasing pattern but slightly drop at Mg-8Zn, and Mg-10Zn alloys. This slight drop in hardness value may be attributed the formation of the secondary phases on these alloys Mg-8Zn, and Mg-10Zn. Because the maximum solubility of zinc in magnesium is 6.2% wt and as highlighted by Yin Dongsong [31] the excess Zinc reacts with Mg and form large amount of Mg, Zn containing phases in the matrix and grain boundary. These phases segregate the matrix and increase the number of crack sources. Therefore, the strength/hardness of the alloy will not be improved. Figure 4.4: The hardness value of Mg-Zn alloys as a function of zinc addition. 44 4.1.4 Tensile Test The tensile strength of the alloy with respect to %wt Zn addition in figure 4.5 also shows an improving trend until 8%wt Zn where the value drop but rise again at 10%wt Zn. The value of the tensile test should follow similar trend as the hardness graph, but this dissimilarity may be related to error or inconsistency in the experiment or the test machine especially for Mg-10Zn, even though the student was very careful to ensure consistency throughout the project. On the other hand the Yield strength value in Table 4.2 shows an ascending pattern of strength for all the alloys. But some rise and fall were observed in the value of the elastic modulus of the alloys. These phenomena of the may be fully explain by the formation of secondary phase as has been shown in figure 4.1(e, f) and 4.2(a, b). As described by Yin Dongsong, excess Zn results in the formation of second phases when reacts with magnesium and become sources of separation in the matrix and the grain boundary, hence, the tensile strength of the alloy will drop. Tensile strenght (MPa) Tensile 180 160 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 159.57 134.82 105.57 139.84 108.28 Mg-Zn alloys 2%Zn 4%Zn 6%Zn 8%Zn %10Zn wt% zn Figure 4.5: The Tensile strength value of Mg-Zn alloys as a function of zinc addition. 45 Table 4.2: The Tensile strength, Yield, and Elastic Modulus value of Mg-Zn alloys Alloys Tensile Strength (MPa) Yield strength (MPa) Modulus (GPa) Mg-2Zn 105.57 54.19 35.94 Mg-4Zn 134.82 65.61 29.93 Mg-6Zn 139.84 83.43 48.66 Mg-8Zn 108.28 89.98 33.29 Mg-10Zn 159.57 128.80 41.55 46 4.1.5 Corrosion Electrochemical Test Figure 4.6 shows the electrochemical polarization curves of the Mg-xZn alloys (x = 2 - 10wt %). It could be seen that the cathodic polarization current of hydrogen evolution reaction (-1.675V) on Mg-6Zn alloy sample was greater than that on Mg-Zn (2, 4, 8, and 10) alloy samples, which indicated that the over potential of the cathodic hydrogen evolution reaction was lower for Mg-6Zn alloy sample. Meaning to say Mg6Zn is less prone to corrosion compare to the other samples. According to Zijian Li [28] generally, the cathodic polarization curves were assumed to represent the cathodic hydrogen evolution through water reduction. Figure 4.6: Electrochemical polarization curves of Mg-Zn alloys under investigation 47 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION Developing optimum Mg-Zn binary alloy composition in terms of tracing the effect of zinc addition in magnesium was the major objective of this project. So, therefore it can conclude that: i. Mg-6Zn alloy with the hardness value of 74.44HV, tensile strength of 139.88MPa, and modulus of 48.66GPa could be considered the optimum composition based on this project work. It shows significant improvement in respond to the zinc addition, virtually better than the other composition studied. Likewise in terms of resistance to corrosion it shows higher potential then the rest of the alloys. ii. In comparison with the reported hardness and tensile strength of the hardest natural bone (16-168HV, and 50-150), and due to the fact that implant material should not be harder than the natural bone, it can be concluded that the properties exhibits by Mg-6Zn are comparable. 48 REFERENCE 1. J. Vormann, Mol Aspects Med, 24 (1-3) (2003), pp. 27–37. 2. R.C. Zeng et al. Advanced Engineering Materials, 10 (8) (2008), pp. B3–B14. 3. D. Upadhyay et al., Materials Science and Engineering A—Structural Materials Properties Microstructure and Processing, 432 (1-2) (2006), pp. 1–11. 4. P.A. Dearnley, Surface & Coatings Technology, 198 (1-3) (2005), pp. 483–490. 5. El-Rahman SSA. Neuropathology of aluminum toxicity in rats (glutamate and GABA impairment). Pharmacol Res 2003; 47(3):189–94. 6. Song G. Control of biodegradation of biocompatible magnesium alloys. Corros Sci 2007; 49(4):1696–701. 7. Mordike BL, Lukác P. Physical metallurgy. In: Friedrich HE, Mordike BL, editors 8. Magnesiumtechnology –metallurgy, design data, applications. Berlin: Springer; 2006. p. 76–7. 9. C.M. Agrawal, Reconstructing the Human Body Using Biomaterials, JOM, Jan 1998, p 31–35 10. M. Long and H.J. Rack, Titanium Alloys in Total Joint Replacement—A Materials Science Perspective, Biomaterials, Vol 19, 1998, p 1621–1639 11. D. Williams, An Introduction to Medical and Dental Materials, Concise Encyclopedia of Medical & Dental Materials, D. Williams, Ed., Pergamon Press and The MIT Press, 1990, p xvii–xx 12. Mader SS. Understanding Human Anatomy and Physiology, the McGraw-Hill Companies, Boston. 2005; ISBN-0072464372 13. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/72869/bone [accessed 31-08-2010]. 49 14. C.O. Bechtol, A.B. Ferguson, Jr., and P.G. Laing, Metals and Engineering in Bone and Joint Surgery, The Williams and Wilkins Company, 1959 15. Johnson AJW, Herschler BA A review of the mechanical behavior of CaP and CaP/polymer composites for applications in bone replacement and repair. Acta Biomaterialia 2010 (Article in Press) 16. T.P. Hoar and D.C. Mears, Corrosion- Resistant Alloys in Chloride Solutions: Materials for Surgical Implants, Proc. R. Soc. (London), SCR.A294 (1439), 1966, p 486–510 17. D.C. Ludwigson, Requirements for Metallic Surgical Implants and Prosthetic Devices, Met. Eng. Q., Vol 5 (No. 3), Aug 1965, p 1–6 18. J.B. Brunski, Metals, Biomaterials Science: An Introduction to Materials in Medicine, B.D. Ratner, A.S. Hoffman, F.J. Schoen, and J.E. Lemons, Ed., Academic Press, 1996, p 37–50 19. Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys.ASM Specialty Handbook (Eds.Avedesian MM,Baker H),ASM International, Materials Park, OH, 1999, pp. 3–6 20. Hume-Rothery W, Raynor GE (1956) Structure of Metals and Alloys, Institute of Metals, London 21. Prasad A. S. (2008). "Zinc in Human Health: Effect of Zinc on Immune Cells". Mol. Med. 14 (5–6): 353–7. doi:10.2119/2008-00033.Prasad PMC 2277319. PMID 18385818 22. Yizao Wan, Guangyao Xiong, Honglin Luo, Fang He, Yuan Huang, Xiaoshong Zhou “Preparation and characterization of a new biomedical magnesium– calcium alloy” Materials and Design 29 (2008) 2034–2037 23. Hui Du, Zunjie Wei, Xinwang Liu, Erlin Zhang “Effects of Zn on the microstructure, mechanical property and bio-corrosion property of Mg–3Ca alloys for biomedical application” Materials Chemistry and Physics 125 (2011) 568–575 24. Jun Wang • Liguo Wang • Shaokang Guan • Shijie Zhu • Chenxing Ren • Shusen Hou “Microstructure and corrosion properties of as sub-rapid solidification Mg– Zn–Y–Nd alloy in dynamic simulated body fluid for vascular stent application” J Mater Sci: Mater Med (2010) 21:2001–2008 50 25. Yuncang Li • Peter D. Hodgson • Cui’e Wen The effects of calcium and yttrium additions on the microstructure, mechanical properties and biocompatibility of biodegradable magnesium alloys J Mater Sci (2011) 46:365–371 26. Erlin Zhang, Liping Xu, Guoning Yu, Feng Pan, Ke Yang ‘In vivo evaluation of biodegradable magnesium alloy bone implant in the first 6 months implantation” Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) 2008 27. E. Aghion • G. Levy “The effect of Ca on the in vitro corrosion performance of biodegradable Mg–Nd–Y–Zr alloy” J Mater Sci (2010) 45:3096–3101 DOI 10.1007/s10853-010-4317-7 28. Zijian Li, Xunan Gu, Siquan Lou, Yufeng Zheng “The development of binary Mg-Ca alloys for use as biodegradable materials within bone Biomaterials” 29 (2008) 1329e1344 29. Yingwei Song, Dayong Shan, Rongshi Chen, Fan Zhang, En-Hou Han “Biodegradable behaviors of AZ31 magnesium alloy in simulated body fluid” Materials Science and Engineering C 29 (2009) 1039–1045 30. X.N. Gu, W.R. Zhou, Y.F. Zheng, Y. Cheng, S.C. Wei, S.P. Zhong, T.F. Xi, L.J. Chen “Corrosion fatigue behaviors of two biomedical Mg alloys – AZ91D and WE43 – In simulated body fluid” Acta Biomaterialia 6 (2010) 4605–4613 31. Yin Dongsong, Zhang Erlin and Zeng Songyan “Effect of Zn content on microstructure, mechanical properties and fracture behavior of Mg-Mn” alloy 1672-6421(2009)01-043-05 32. Shaoxiang Zhang, Xiaonong Zhang, Changli Zhao, Jianan Li, Yang Song, Chaoying Xie, Hairong Tao, Yan Zhang, Yaohua He, Yao Jiang, Yujun Bian “Research on an Mg–Zn alloy as a degradable biomaterial” Acta Biomaterialia 6 (2010) 626–640 51 APPENDIX A Compositional Analysis of the as- cast Samples Compositional Analysis of the as- cast Samples of Mg-2Zn 52 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-2Zn 53 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-4Zn 54 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-4Zn 55 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-6Zn 56 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-6Zn 57 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-8Zn 58 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-8Zn 59 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-10Zn 60 Compositional Analysis for the as- cast Sample Mg-10Zn 61 APPENDIX B The Stress/Strain Graphs for the alloys Samples The Stress/Strain Graphs for Mg-2Zn 62 The Stress/Strain Graphs for Mg-4Zn 63 The Stress/Strain Graphs for Mg-6Zn 64 The Stress/Strain Graphs for Mg-8Zn 65 The Stress/Strain Graphs for Mg-10Zn 66 APPENDIX C Polarization Curves of the Samples Polarization Curves of Mg-2Zn Mg-2Zn 67 Polarization Curves for Mg-4Zn Mg-4Zn 68 Polarization Curves for Mg-6Zn Mg-6Zn 69 Polarization Curves for Mg-8Zn Mg-8Zn 70 Polarization Curves for Mg-10Zn Mg-10Zn 71