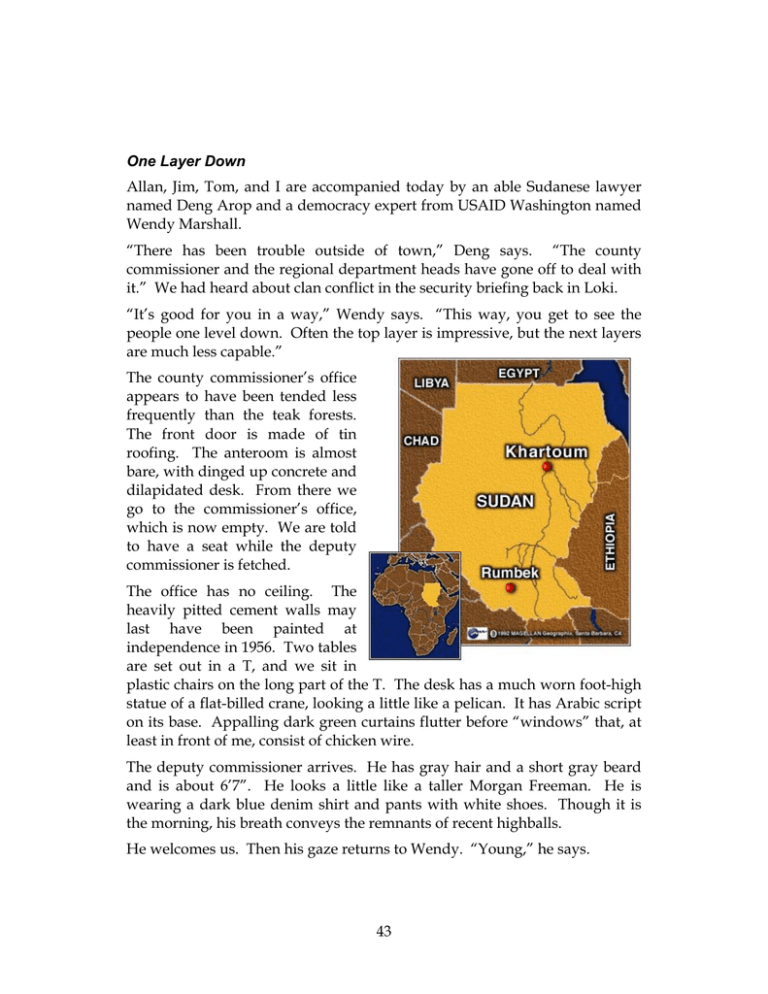

Allan, Jim, Tom, and I are accompanied today by an... named Deng Arop and a democracy expert from USAID Washington... One Layer Down

advertisement