Accounts of Louis XIV by Saint-Simon and Madame de Savigné

advertisement

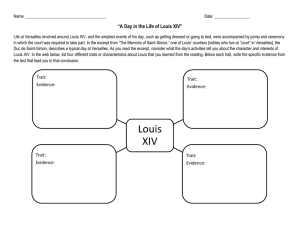

Accounts of Louis XIV by Saint-Simon and Madame de Savigné Questions: 1. According to Saint-Simon, what was Louis XIV like? Do you think this is an accurate portrait? 2. Why did Vatel kill himself? What does this show about the life of the royal court? Saint-Simon Louis XIV's vanity was without limit or restraint; it colored everything and convinced him that no one even approached him in military talents, in plans and enterprises, in government. Hence those pictures and inscriptions in the gallery at Versailles which disgust every foreigner; those opera prologues that he himself tried to sing; that flood of prose and verse in his praise for which his appetite was insatiable; those dedications of statues copied from pagan sculpture, and the insipid and sickening compliments that were continually offered to him in person and which he swallowed with unfailing relish; hence his distaste for all merit, intelligence, education, and, most of all, for all independence of charactcr and sentiment in others; his mistakes of judgment in matters of importance; his familiarity and favor reserved entirely for those to whom he felt himself superior in acquirements and ability; and, above everything else, a jealousy of his own authority which determined and took precedence of every other sort of justice, reason, and consideration whatever.... The king's great qualities shone more brilliantly by reason of an exterior so unique and incomparable as to lend infinite distinction to his slightest actions; the very figure of a hero, so impregnated with a natural but most imposing majesty that it appeared even in his most insignificant gestures and movements, without arrogance but with simple gravity; proportions such as a sculptor would choose to model; a perfect countenance and the grandest air and mien ever vouchsafed to man; all these advantages enhanced by a natural grace which enveloped all his actions with a singular charm which has never perhaps been equaled. He was as dignified and majestic in his dressing gown as when dressed in robes of state, or on horseback at the head of his troops. He excelled in all sorts of exercise and liked to have every facility for it. No fatigue nor stress of weather made any impression on that heroic figure and bearing; drenched with rain or snow, pierced with cold, bathed in sweat or covered with dust, he was always the same. I have often observed with admiration that except in the most extreme and exceptional weather nothing prevented his spending considerable time out of doors every day. A voice whose tones corresponded with the rest of his person; the ability to speak well and to listen with quick comprehension; much reserve of manner adjusted with exactness to the quality of different persons; a courtesy always grave, always dignified, always distinguished, and suited to the age, rank, and sex of each individual, and, for the ladies, always an air of natural gallantry. So much for his exterior, which has never been equaled nor even approached. In whatever did not concern what he believed to be his rightful authority and prerogative, he showed a natural kindness of heart and a sense of justice which made one regret the education, the flatteries, the artifice which resulted in preventing him from being his real self except on the rare occasions when he gave way to some natural impulse and showed that, - prerogative aside, which choked and stifled everything, - he loved truth, justice, order, reason, - that he loved even to let himself be vanquished. Nothing could be regulated with greater exactitude than were his days and hours. In spite of all his variety of places affairs, and amusements, with an almanac and a watch one might tell, three hundred leagues away, exactly what he was doing.... Except at Marly, any man could have an opportunity to speak to him five or six times during the day; he listened, and almost always replied, "I will see," in order not to accord or decide anything lightly. Never a reply or a speech that would give pain; patient to the last degree in business and in matters of personal service; completely master of his face, manner, and bearing; never giving way to impatience or anger. If he administered reproof, it was rarely, in few words, and never hastily. He did not lose control of himself ten times in his whole life, and then only with inferior persons, and not more than four or five times seriously. Madame de Savigné It is Sunday, the 26th of April; this letter will not go till Wednesday. It is not really a letter, but an account, which Moreuil has just given me for your benefit, of what happened at Chantilly concerning Vatel. I wrote you on Friday that he had stabbed himself; here is the story in detail. The promenade, the collation in a spot carpeted with jon quils, - all was going to perfection. Supper came; the roast failed at one or two tables on account of a number of unexpected guests. This upset Vatel. He said several times, "My honor is lost; this is a humiliation that I cannot endure." To Gourville he said, "My head is swimming; I have not slept for twelve nights; help me to give my orders." Gourville consoled him as best he could, but the roast which had failed, not at the king's, but at the twenty-fifth table, haunted his mind. Gourville told Monsieur le Prince about it, and Monsieur le Prince went up to Vatel in his own room and said to him, "Vatel, all goes well; there never was anything so beautiful as the king's supper." He answered, "Monseigneur, your goodness overwhelms me. I know that the roast failed at two tables." "Nothing of the sort," said Monsieur le Prince. "Do not disturb yourself, all is well." Midnight comes. The fireworks do not succeed on account of a cloud that overspreads them (they cost sixteen thousand francs). At four o'clock in the morning Vatel is wandering about all over the place. Everything is asleep. He meets a small purveyor with two loads of fish and asks him, "Is this all?" "Yes, sir." The man did not know that Vatel had sent to all the seaport towns in France. Vatel waits some time, but the other purveyors do not arrive; he gets excited; he thinks that there will he no more fish. He finds Gourville and says to him, "Sir, I shall not be able to survive this disgrace." Gourville only laughs at him. Then Vatel goes up to his own room, puts his sword against the door, and runs it through his heart, but only at the third thrust, for he gave himself two wounds which were not mortal. He falls dead. Meanwhile the fish is coming in from every side, and people are seeking for Vatel to distribute it. They go to his room, they knock, they burst open the door, they find him lying bathed in his blood. They send for Monsieur le Prince, who is in utter despair. Monsieur le Duc bursts into tears; it was upon Vatel that his whole journey to Burgundy depended. Monsieur le Prince informed the king, very sadly; they agreed that it all came from Vatel's having his own code of honor, and they praised his courage highly even while they blamed him. The king said that for five years he had delayed his coming because he knew the extreme trouble his visit would cause. He said to Monsieur le Prince that he ought not to have but two tables and not burden himself with the responsibility for everybody, and that he would not permit Monsieur le Prince to do so again; but it was too late for poor Vatel. Gourville, however, tried to repair the loss of Vatel, and did repair it. The dinner was excellent; so was the luncheon. They supped, they walked, they played, they hunted. The scent of jonquils was everywhere; it was all enchanting. Saint-Simon's Portrait of Louis XIV from "Parallele des trois premiers rois Bourbons" (written in 1746), Ecrits inedits de Saint-Simon I, 84 sqq, in J.H. Robinson, Readings in European History 2 vols. (Boston: Ginn, 1906), 2:285-286. Madame de Savigné's Portrait of Louis and his Court Entertained by the Prince of Condé at Chantilly (1671) from Lettres de Madame de Savigné (April 26, 1671), ed. de Sacy (1861 sqq), Vol. I, 414 sqq, in J.H. Robinson, Readings in European History, 2 vols. (Boston: Ginn, 1906), 2:283-285. Scanned by Brian Cheek, Hanover College, November 12, 1995. Inside the Court of Louis XIV, 1671 The seventy-two year reign of Louis XIV was marked by an opulent extravagance best exemplified by the construction of his palace at Versailles in 1682. Here, the entire French nobility was expected to take residence and to participate in elaborate ceremonies, festivals and dinners. Louis' motivation was not based solely on his desire to have a good time but was a means of simultaneously controlling the nobility, reducing their power and watching for any potential rivals. Prior to the construction of Versailles, Louis kept an eye on the nobility by requiring that they accompany him wherever he may go. When the king traveled, he did so at the head of a great lumbering retinue of hundreds of lesser princes - all of whom had to be fed and entertained at each stop. "My honor is lost..." We gain some insight into life at the court of Louis XIV through a letter written by Madame de Sevigne to a friend in 1671. Louis has decided to make war on Holland and has traveled to Chantilly to meet with his commander. A great feast is planned to take place in the forest supervised by Vatel, the "Prince of Cooks." "It is Sunday, the 26th of April; this letter will not go till Wednesday. It is not really a letter, but an account, which Moreuil has just given me for your benefit, of what happened at Chantilly concerning Vatel. I wrote you on Friday that he had stabbed himself; here is the story in detail. The promenade, the collation in a spot carpeted with jonquils - all was perfection. Supper came; the roast failed at one or two tables on account of a number of unexpected guests. This upset Vatel. He said several times: 'My honor is lost; this is a humiliation that I cannot endure.' To Gourville he said. 'My head is swimming; I have not slept for twelve nights; help me to give my orders.' Gourville consoled him as best he could, but the roast which had failed (not at the king's, but at the twenty-fifth table), haunted his mind. Gourville told Monsieur le Prince about it, and Monsieur le Prince went up to Vatel in his own room and said to him, 'Vatel, all goes well; there never was anything so beautiful as the king's supper.' He answered, 'Monseigneur, your goodness overwhelms me. I know that the roast failed at two tables.' 'Nothing of the sort,' said Monsieur le Prince. 'Do not disturb yourself, all is well.' Midnight comes. The fireworks do not succeed on account of a cloud that overspreads them (they cost sixteen thousand francs). At four o'clock in the morning Vatel is wandering about all over the place. Everything is asleep. He meets a small purveyor with two loads of fish and asks him, 'Is this all?', 'Yes, sir.' The man did not know that Vatel had sent to all the seaport towns in France. Vatel waits some time, but the other purveyors do not arrive; he gets excited; he thinks that there will be no more fish. He finds Gourville and says to him, 'Sir, I shall not be able to survive this disgrace.' Gourville only laughs at him. Then Vatel goes up to his own room, puts his sword against the door, and runs it through his heart, but only at the third thrust, for he gave himself two wounds which were not mortal. He falls dead. Meanwhile the fish is coming in from every side, and people are seeking for Vatel to distribute it. They go to his room, they knock, they burst open the door, they find him lying bathed in his blood. They send for Monsieur le Prince, who is in utter despair. Monsieur le Duc bursts into tears; it was upon Vatel that his whole journey to Burgundy depended. Monsieurie Prince informed the king, very sadly; they agreed that it all came from Vatel's having his own code of honor, and they praised his courage highly even while they blamed him... Gourville, however, tried to repair the loss of Vatel, and did repair it. The dinner was excellent; so was the luncheon. They supped, they walked, they played, they hunted. The scent of jonquils was everywhere; it was all enchanting." References: Madame de Sevigne's account appears in Robinson, James Harvey (ed.) Readings in European History (1906); Carr, John Laurence, Life in France under Louis XIV (1970).