2001 Honorary Degree Recipients and Commencement Speakers Leslie H. Gelb r (

advertisement

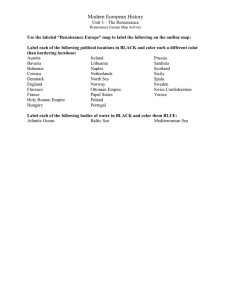

2001 Honorary Degree Recipients and Commencement Speakers click on the names below to view bios or on “remarks” to view speeches. Leslie H. Gelb, Commencement Speaker (remarks) Susan Elizabeth Stearn, Student Speaker (remarks) Leslie H. Gelb Leslie Gelb, one of America’s leading experts on foreign policy, is president of the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization devoted to improving America’s understanding of foreign policy. A trustee of The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and trustee emeritus of Tufts University, he serves on the boards of the Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs, the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, the Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute for International Studies at Brown University, and The Nixon Center. Gelb is an advisory member for the Center for Press, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. He is also a member of the International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Trilateral Commission, and he is a fellow at the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Gelb is the recipient of several distinguished awards including the Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Journalism, the State Department’s Distinguished Honor Award, and the Pentagon’s Distinguished Service Award. He served as an assistant secretary of state in the Carter Administration, as director of the Pentagon Papers Project, and as executive assistant to U. S. Senator Jacob Javits. Gelb is the author of several books, including Anglo-American Relations, Toward a Theory of Alliances, The Unmaking of American Foreign Policy, Claiming the Heavens (Star Wars), and coauthor of The Irony of Vietnam: The System Worked, Our Own Worst Enemy. He received a Ph.D. degree from Harvard University and lives in New York City with his wife, Judith Cohen. The father of three children, he received the Father of the Year Award in 1993. Remarks by Leslie H. Gelb "Challenges and Opportunities: The Renaissance and Today" It is a pleasure to be here with you, President Upham, Chairman of the Board Larry Glenn, an old colleague of mine and past president of yours, John Maguire (we started out our careers together as young professors), and my good and close friend, also on your board of trustees, Skip Stein, to whom all criticisms of my address should be directed. Congressman Dreier reminded me as we were parading to the podium that there is no such thing as a good 25-minute graduation address and nothing shorter than eight minutes is close to a great foreign policy address. I propose to be near great. I want to talk to you because I wish I were you. And I wish I were you not because I would trade my life or my career—I’ve been blessed—but because you have an opportunity to escape 500 years of history. A history of warfare, the fact of war or the threat of war. You actually have the chance, given the moment of history in which you live, to do some special things. I am going to lay out that argument to you. I think you are living at the beginning of the second of the two “big bangs” in international history. The first was during the Renaissance period when international space was created by the kings who fashioned the nation state. The second big bang occurred about 10 years ago with the collapse of the Soviet Union where new international space has been created with new opportunities, new dangers, and new challenges. How do you know that you’re in the midst of new and seminal periods when things are possible, when you can do things that you haven’t been able to do for 500 years? One way to tell is that experts like myself are wrong almost all the time. If you look at what we have been saying to you for the last 10 years, our record is almost horrendously and consistently inaccurate. Almost everything we said would not happen, did. And almost everything we said would happen, didn’t. That goes from, the handshake on the White House lawn between Arafat and Rabin, which will come back again in years to come, the settlement between de Clerk and Mandella in South Africa, the collapse of the Soviet Union. Japan was supposed to be at the top of the international economic ladder. It is not; it is having troubles. The Soviet empire was to live forever; it collapsed. But experts who really are smart and know a lot are that wrong so often. It means that there has been systemic change, a profound change in context. And that occurs—the surprises, the discontinuities—when the fundamental realties of life are changing underneath our feet. And the fundamental realities are really determined by forces such as: Who holds power? Is it the nationstate? Who within the nation-state? Is it new? Is it a new form of international activity, like nongovernmental organizations, or new power for business? Is it how people create wealth, or is it how they gain knowledge, their information systems? All of those forces are set loose today just as they were during the Renaissance era. International space is being created and can be shaped by you just as it was shaped by the kings in the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. In the Renaissance they also had globalization. In effect they went from trade among villages to trade from Venice to Peking. They knew globalization then, and it was a source of creating great wealth. They knew about information revolutions then, just as we do now. They had the printing press, and in many ways the printing press was an even more profound revolution for information than what we are going through today. There is an expansion of access to information today. With the printing press, they went in effect from near zero percent of the population able to read and write to opening up the vernacular native languages to people throughout Europe. They would all have the potential to read and write. Above all, of course, then they had the nation-state coming into being and shaping the rest of the international system. They knew what wars were then as we do now. There were ethnic and civil conflicts pockmarking the globe then. There were religious conflicts then. The kind of conflicts that occur as empires fall, and as new forms are being shaped. But look at where we are now, to see where our opportunities and dangers will be. We are in the midst of a profoundly important globalization process. But it’s not as important and not as new as a lot of people say, because its not as if we haven’t had globalization before, dating back to the Renaissance. Yes, there’s more trade, but there always has been trade. Yes, there is a lot of investment from industrialized countries today to nonindustrialized ones, but there was even more so in the beginning of the twentieth century. Yes, there is dissemination of information today through faxes and the Internet, but that’s happened before as well with the telegraph and printing press. What gives us the greatest opportunity is the change in the actors of international space. The nationstate is still the most important factor in that space, but it occupies a smaller part of it now. There are other actors who play a very important role, such as nongovernmental organizations and business. States can’t keep up with all of this. Our own trade for example has nearly tripled over the last 20 years as a percentage of our gross national product. One and a half trillion dollars crosses international boundaries today, really without reference to governmental decisions. Nations and leaders of nations spent most of their time in times past, planning for war, building economies to better their nation’s wealth and to prepare for war, playing the balance of power game. Today’s possibilities are different. You can do other things. There is no balance of power game going on globally. There is us, and there are a whole bunch of other powers that do not compare with us on a global level. We spend about $310 billion dollars on defense—more than the next seven biggest spenders on defense around the world, more than China, Russia, England, France, etc. put together. No one matches our economic and military power globally—there is no one to balance us. But what do we make of this world? How do we take advantage of the opportunities? The people in the Renaissance era did it, and they did it the right away. They understood. We are having trouble with it; we are struggling with it. One of the reasons they caught on to newness and the opportunity during the Renaissance was they were Renaissance people. They knew everything under the sun. They were educated in every field—history, mathematics, politics, literature—and they could make the connections between these things. Insights come from making connections. Secondly, they were in a position to understand what was going on to them, and to take advantage of it, because they believed they could. They believed in truth. Even though the Renaissance was a re-assertion of Greek learning, the humanists who dominated the intellectual life of the Renaissance—people like Erasmus—believed in the fundamental harmony of Christian values and pragmatic Greek learning. They didn’t believe there were contradictions there. They believed they fit together, and that it was the job of man to reconcile values and pragmatism. Today, if there is a hallmark to what goes on intellectually, it’s that awful word, to me “deconstructionism.” It asserts that the one thing that is important is words and that there is no truth. You’ve got to believe that there is truth in order to seek it, in order to take advantage of the opportunity in front of us. One of the greatest opportunities in front of us is to redefine what is national security, what our nationstate should stand for, what the United States should stand for. Yes, traditional national security concerns remain important, and we ought to spend that $310 billion on defense. We ought to make sure we are taken care of in the traditional realm and that we begin to deal with other security threats such as terrorists. But there are whole new and vital dimensions to our security, such as economics. If we have a holdover, it’s China. It isn’t because China thinks we are about to invade them—because they need us economically—our trade, our investment, and what our economic involvement with them triggers with other nations. Economics, the well-being of people within nations, has now become every bit as important to the purpose of a nation as traditional national security concerns. And there are new dimensions still to national security, such as environment. The hole in the ozone layer is not just over Peoria’ it is over the whole world. Global warming is a global phenomenon. Health problems like AIDS mean that someone can get sick and die in Africa, that nations can fail as well, and that refugees and instability occur. Those are international problems. Hoof and mouth disease travels, destroys lives for farmers and food for countries. Health, environment, drugs…these are all now new dimensions of national security if you make the fight for it. But you will have to make the fight for it. It won’t come naturally. My generation still dominates the discussion of what is national security. We served our county well during the years of the cold war, but now it’s time for something new. Someone, namely you, has to make the fight to redefine national security. I leave with one thought, in the words of Art Buckwald, “My generation— your parents, your seniors—have left you with such a perfect world. Don’t screw it up.” Susan Elizabeth Stearn Susan Elizabeth Stearns earned dual degrees—a Master of Business Administration with concentrations in strategy and finance, and a Master of Arts in Politics, Economics and Business. She was attracted to the Peter F. Drucker Graduate School of Management and CGU by its reputation for training future leaders in both the public and private sectors. Stearns received her B.A. degree in U. S. history from Northwestern University. She is also a graduate of the Coro Fellows Program in Public Affairs. Her professional career includes working for the late Missouri Governor Mel Carnahan on policy and political strategy. In Missouri, she established a pubic-private partnership to oversee welfare reform in the St. Louis region. Prior to entering CGU, she lived in Eugene, Oregon, and worked with corporate, nonprofit, and government leaders to design a child abuse prevention initiative. While at the Drucker School, Stearns served as president of the Drucker School Student Association and was named a member of the Beta Gamma Sigma national academic honors society. She was also a recipient of both the Thomas McKernan Automobile Club of Southern California Fellowship and the George Kozmetsky Fellowship. Stearns gratefully acknowledges their support in the completion of her education. Stearns believes that shaping the future depends upon the collaboration of leaders from the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Remarks by Susan Elizabeth Stearn President Upham, Board Members, Faculty, Administrators, Fellow Students and Guests: On behalf of the graduates, I would like to thank our friends and families who made long journeys to be with us as we celebrate our graduation and who have supported us through our educations. As the Class of 2001, we are officially the first graduating class of the 21st century. This century is characterized by terms such as: change, uncertainty, ambiguity, and having new “rules of the game.” Whether we studied education or information science, philosophy or management, economics or policy, whether we are American or international, we face a complex future. We all will be moving into organizations and communities that will be defining strategies to thrive in all this uncertainty. Today, I want to talk about the importance of our committing to a leadership role in helping these organizations and communities frame these strategies. In the late 1960s, the anthropologist Margaret Mead, completed a study of how cultures transmit knowledge from one generation to another. Based upon her research of societies across different continents and eras, she classified three types of cultures. In early cultures, children learned from the older generation. Parents and grandparents prepared their children for a life exactly like their own. In cultures characterized by pioneers and immigrants, both children and adults learned the new ways from their peers, rather than their elders. Mead saw in the post World War II era a third type of culture. Adults learned from their children. It was the young with their new experiences who initiated change and transmitted their ideas to their elders. Mead recognized how profoundly this dynamic—younger generations teaching older generations— would shape the new millennium. This dynamic still applies today. Margaret Mead’s analysis helps me understand the significance of my generation’s leadership role in the 21st century. Unlike the rebellious youth of the 1960s, my generation wants to use our new ideas to transform existing organizations and to help them adapt to the new millennium. We want to be involved in decision making and to be a part of designing the solutions. We want our voices to be heard. I came to CGU to acquire the skills that would earn me a seat at the table. President Upham describes the “acquisition of knowledge as being facilitated by learned faculty and informed peers.” I feel fortunate to have studied at an institution that values the student-faculty interaction. My professors have taught me to think analytically and to ask probing questions. I am inspired by hearing my teachers say they continue to learn from their students. I have also learned from my peers. They have given me a global perspective and taught me to listen and to consider problems from new points of view. I leave CGU grateful to my peers and professors. They helped me refine my vision of leadership and recognize the commitment it requires. Today I want to challenge my classmates to think about what a commitment to leadership means to each of you. We all must acknowledge our role in shaping the future of our professions, our nations, and our world. We all have a responsibility to seek leadership opportunities and be involved in decision-making. We all must demand our seats at the table. Leadership in the 21st century means being able to bring all the generations together to embrace the uncertainty that lies ahead. We must build on the wisdom of our elders and relate to them our new experiences and vision for the future. We have to earn their trust by showing that we can provide viable solutions to current and unprecedented problems. We must be ready to hold doors open to those younger than ourselves. Each new generation will have the experiences and ask relevant questions from which we will learn. We must remain flexible and incorporate each new generation’s ideas. Above all, it is our responsibility to prepare future leaders. As Margaret Mead noted, we must teach them not what to learn, but how to learn and not what to be committed to, but the value of commitment. Congratulations to all the graduates.