A DESCRIPTIVE STUDY OF TRIBAL TEMPORARY ASSISTANCE FOR OPRE Report 2013-34

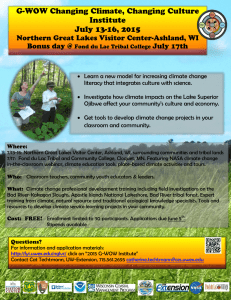

advertisement