Volume XXV Number 1 2007

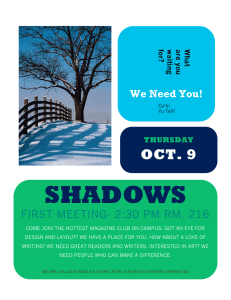

advertisement