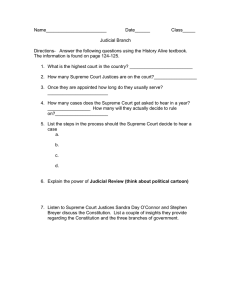

T L S C

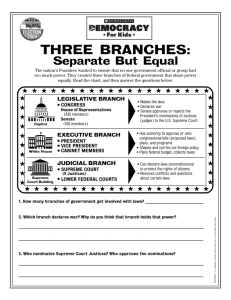

advertisement