Dynamics of the Gender Gap for Young s

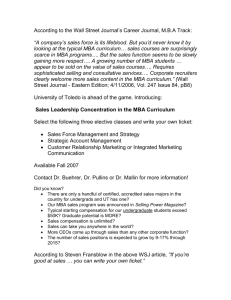

advertisement