CRIMINAL JUSTICE INTERVENTIONS FOR OFFENDERS WITH MENTAL ILLNESS: EVALUATION OF

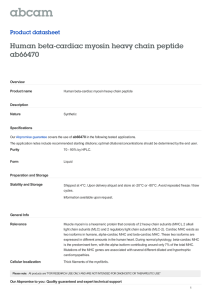

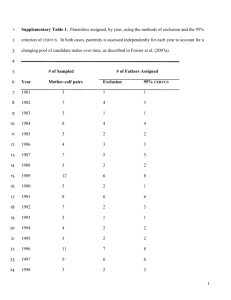

advertisement