CLEVELAND AND CUYAHOGA COUNTY, OHIO May 2014

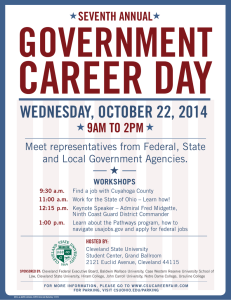

advertisement