Implications of Immigration Enforcement Activities for the Well-

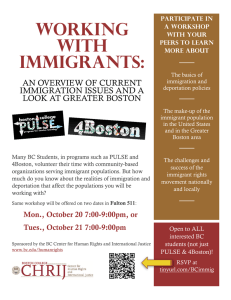

advertisement