Document 14469358

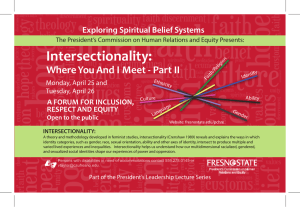

advertisement

SOC 138B SOCIOLOGY OF RACE, CLASS & GENDER SPRING, 2016 Meeting Times: Tuesdays and Thursdays, 3:30pm-­‐4:50pm Lecture Hall: Golding Judaica Center 101 Professor D. Wallace Office: Abraham Shapiro Academic Complex (ASAC) 214 E-­‐mail address: dwallace@brandeis.edu Phone number: 781-­‐736-­‐2088 Skype: derron.jr.wallace Office Hours: Wednesday 10am-­‐12pm, and by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION This course examines race, class and gender as influential, interlocking dimensions of social identities that shape institutions, dynamics, processes, and cultures. Rooted in the rich analytical traditions of sociology, Black studies, ethnic studies, and women’s studies, the study of race, class and gender charts intellectual terrain about the politics of sameness, difference, commonality and solidarity from the early 20th century to present. The course draws on a variety of media to analyze how race, class and gender (re)create forms of domination and subordination in schools, labor markets, families, the criminal justice system, the health care system, and civil society. Based on comparative, historical, quantitative and ethnographic studies, course readings and lectures provide an introductory interrogation of racism, sexism, classism and related forms of oppression, noting their varying formations across space and time, and their joint operation in the lived experiences of historically marginalized social groups. The Sociology of Race, Class & Gender challenges essentialist claims of victimhood, and outlines the theoretical, methodological and empirical challenges of studying race, class and gender rigorously. This course is geared towards students interested in the issues of power, justice and social change in social institutions and the wider society. COURSE OBJECTIVES By the end of the course, students will be able to: • Understand and critique theoretical and conceptual approaches used by sociologists to explore race, class and gender in the U.S.; • Identify the similarities and differences between social groups and their importance for coalition-­‐building; • Demonstrate an awareness of the theoretical debates about Du Boisian sociology, intersectionality and Bourdieusian sociology; • Decipher how related factors such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, language and culture are interwoven into the lived experiences of dominant and minoritised communities; 1 • Improve their writing, analytical and presentation skills through intensive assignments. COURSE REQUIREMENTS The following are core requirements for all students enrolled in the course: I. ATTENDANCE Class attendance is mandatory. It is important that all students attend class sessions in order for all of us to discuss and decipher the course materials and lectures as a collegial community of learners. Attendance will be taken during each class period and students will be required to attend the entire class session to receive full credit. In case of illness or other legitimate reasons for absence, it is the student’s responsibility to inform Prof. Wallace in advance. Every absence after two instructor-­‐excused absences will result in the reduction of your overall grade by a third of a letter grade (e.g. an A becomes an A-­‐, a B+ becomes a B, etc.). To earn full attendance credit, you must come to class prepared to discuss the readings assigned for that session and with the necessary materials, required books, articles, paper, and notes. II. PARTICIPATION Active class participation is expected of all students. The dynamics of the class are contingent upon all those in the room. Active participation includes voicing critical questions about course materials, engaging in class discussions, working with peers in small-­‐group discussions, and co-­‐leading one class debate. Please be advised that texting, e-­‐mailing and commenting on online media platforms of any sort (Facebook, Twitter, Yik Yak, and the like) will not be condoned during class. Students found doing this will be asked to leave and will lose 10% on their mid-­‐term or final assignment. Students are also encouraged to silence all cellphones before class begins. III. INTEGRITY Because Brandeis University is a collegial community deeply committed to the free exchange of ideas, academic integrity is expected of all its members. Plagiarism is not at all acceptable. Students who enroll in this class hereby agree to conduct themselves responsibly and are expected to participate in the creation of a welcoming space in which all students can discuss race, racism, sexism, poverty, identities, inequalities and related matters. To maintain a ‘safe space’ in the class, students are expected to challenge ideas and not the individuals; respectful disagreement is always welcome. This is a professional courtesy all are required to maintain. For more details on academic integrity, please refer to the Brandeis Rights and Responsibilities handbook. 2 GRADED REQUIREMENTS • • • • • • Class Participation: 10% of grade Quizzes: 25% of grade Class Conference: 10% of grade Response Paper: 10% Midterm Exam: 20% of grade Final Exam: 25% of grade Paper Format All written assignments should use the following formatting guidelines: • Name, assignment, and date in the top left-­‐hand corner • Page numbers on every page • Double-­‐spaced • One-­‐inch margins on all sides • Times New Roman, 12pt • Use the following file name format to save your paper: FirstName_rcg.doc GRADING NOTES In this class, work will be evaluated on the basis of: depth of analysis (40%), clarity in the presentation of ideas (40%) and grammar/punctuation/spelling (20%). RELATED COURSE POLICIES Assignments: All assignments should be professional in appearance. All papers and exams should be typed, double-­‐spaced, stapled once in the top right-­‐hand corner. Please keep a copy of all written work before submitting. Do not use any decorative covers or binders for any assignment. Assignments received in this fashion will be returned ungraded. Unless otherwise noted, all papers should be emailed to Prof. Wallace at dwallace@brandeis.edu Deadlines: All deadlines are firm. Extensions will only be granted under exceptional circumstances. Assignments not turned in by the due date and time listed on the course schedule will be considered late; students will be penalized for this. Assignments submitted after the outlined deadline will lose 30% of the final grade; ones submitted more than an hour after the deadline will lose 50% of the final grade; papers submitted after 24 hours will not be accepted. It is the responsibility of the student to turn in assignments on time. 3 Extra Credit: Students will be afforded two extra credit opportunities throughout the course of the semester. The extra credit assignments will be announced a week before they are due. These may come in the form of additional pop quizzes, current affairs analyses or participation in select on-­‐campus events hosted by the Departments of Sociology African & Afro-­‐American Studies and/or Social Justice & Social Policy. Computer Usage: Laptops, i-­‐Pads or other relevant electronic devices are allowed, but only for accessing the assigned course readings on LATTE. Use of electronic devices for any other purpose is strictly prohibited; violations will not be excused. Any violation of this policy will result in the prohibition of your electronic device for future use in the classroom during the course. Disability Services: "If you are a student who needs academic accommodations because of a documented disability, please contact me and present your letter of accommodation as soon as possible. If you have questions about documenting a disability or requesting academic accommodations, you should contact Beth Rodgers-­‐Kay in Academic Services (x6-­‐3470 or brodgers@brandeis.edu.) Letters of accommodation should be presented at the start of the semester to ensure provision of accommodations, and absolutely before the day of an exam or test. Accommodations cannot be granted retroactively." COURSE SCHEDULE January 14: Overview | Introductory Reflexive Analysis McCorkel, J. & Myers, K. 2003. “What Difference Does Difference Make? Position and Privilege in the Field.” Qualitative Sociology. 26(2), pp. 199-­‐231. PART I: AN INVITATION TO CRITICAL SOCIOLOGICAL INQUIRY January 19: Foundational Frames| Assessing the Field of American Sociology Morris, A. 2015. “Preface.” Pp. ix-­‐xxiii in The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and The Birth of Modern Sociology, California: University of California Press. Morris, A. 2015. “Du Bois, Scientific Sociology and Race.” Pp. 15-­‐54 in The Scholar Denied: W.E.B. Du Bois and The Birth of Modern Sociology, California: University of California Press. January 21: Du Boisian Sociology 4 Itzigsohn, J. & Brown, K. 2015. “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Phenomenology of Racialized Subjectivity.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 12 (2): 231-­‐48 Recommended Hancock, A.M. 2005. “W.E.B. DuBois: Intellectual Forefather of Intersectionality?” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics, Culture, and Society 7(3-­‐4): 74-­‐84. January 26: Sexism & Classism in Du Boisian Sociology? Griffin, F, J. 2000. “Black Feminists and Du Bois: Respectability, Protection, and Beyond.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 56(8): 28-­‐40. January 28: Intersectionality as Theory & Activism Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review, 43 (6): 1241-­‐1299. Collins, P. H. 2015. “Intersectionality’s Definitional Dilemmas.” Annual Review of Sociology 41 (3): 3.1-­‐3.20. **Class Caucus** February 2: Pedagogies of Inclusion | Practices of Intersectionality Cho, S. Crenshaw, K. and McCall, L. 2013. “Toward a Field of Intersectionality Studies: Theory, Applications, and Praxis.” Signs 38(4): 785-­‐810. Patil, V. 2013. “From Patriarchy to Intersectionality: A Transnational Feminist Assessment of How Far We've Really Come.” Signs 38(4): 847-­‐867 MacKinnon, C.A. 2013. “Intersectionality as Method: A Note.” Signs 38(4): 1019-­‐1030 Davis, K. 2008. “Intersectionality as Buzzword: A Sociology of Science Perspective on What Makes a Feminist Theory Successful.” Feminist Theory 9(1): 67-­‐85. Choo, H. and Ferree, M 2010. “Practicing Intersectionality in Sociological Research: A Critical Analysis of Inclusions, Interactions, and Institutions in the Study of Inequalities.” Sociological Theory 28(2): 129-­‐149. Pyke, K. and Johnson, D. 2003.“Asian American Women and Racialized Femininities: ‘Doing’ Gender across Cultural Worlds.” Gender & Society 17 (1): 33-­‐53. 5 Greenebaum, J. 1999. “Placing Jewish Women into the Intersectionality of Race, Class and Gender.” Race, Gender & Class. 6(4): 41-­‐60. February 4: Organizing the 2016 Class Conference PART II: AN INVESTIGATION OF INEQUALITY IN SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS February 9: Disciplinary Differences in US Schools Win, C. 2015. “Against Captivity: Black Girls and School Discipline Policies in the Afterlife of Slavery.” Educational Policy, 29 (1): 1-­‐26. Recommended Morris, E. 2005. “’Tuck in that Shirt!’: Race, Class, Gender and Discipline in an Urban School.” Sociological Perspectives, 48 (1): 25-­‐48. February 11: Racialized Class Inequality in U.S. Schools Anyon, J. 1980. “Social class and the hidden curriculum of work,” Journal of Education, 162 (1): 67-­‐92 Ladson-­‐Billings, G. 2006. “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools,” Educational Researcher, 35 (7): 3-­‐12. February 16: NO CLASSES February 18: NO CLASSES February 23: Racialized Gender Inequality in Family Relations Lareau, A. 2002. “Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families,” American Sociological Review, 67 (5): 747-­‐776. Recommended Lopez, N. 2003. “Homegrown: How the family does gender.” Pp. 113-­‐140 in Hopeful girls, Troubled boys: Race and Gener Disparity in Urban Education. New York: Routledge. February 25: Invisible Labor?: Women’s Work Strategies 6 Roberts, Dorothy. 1999. “Welfare’s Ban on Poor Motherhood.” Pp. 152-­‐170 in Whose Welfare? Edited by Gwendolyn Mink. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. Ortiz, Vilma. 1997. “Family Economic Strategies among Latinas.” Race, Gender & Class. 4(2): 91-­‐106. March 1: Division of Labor: The Influence of Race & Gender Browne, I. & Misra, J. 2003. “The Intersection of Gender and Race in the Labor Market,” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (1): 487-­‐513. Glenn, E. N. 2002. “Introduction,” and “Integrating Race and Gender” Pp. 1-­‐17 in Unequal Freedom: How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor, Cambridge: Harvard University Press. **MIDTERM EXAM** March 3: Labor Market Discrimination Budig, M. J. 2002. “Advantage and the Gender Composition of Jobs: Who Rides the Glass Escalator?” Social Problems 49 (1): 258 -­‐277. Acker, J. 2006. “Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class and Race in Organizations,” Gender & Society, 20 (1): 441-­‐464. March 8: Inequality in the Criminal Justice System Burgess-­‐Proctor, A. 2006. “Intersections of Race, Class, Gender, and Crime: Future Directions for Feminist Criminology.” Feminist Criminology 1 (1): 27-­‐47. Hagan, J., Shedd, C. & Payne, M. 2005. “Race, Ethnicity, and Youth Perceptions of Criminal Justice.” American Sociological Review 70 (3): 381-­‐407. March 10: The War on Drugs & Deviance Bobo, L. & Thompson, V. 2006. “Unfair by design: The War on Drugs, Race and the Legitimacy of the Criminal Justice System.” Social Research 73 (2): 445-­‐ 72. Sampson, R. & Lauritsen, J. 1997. “Racial & Ethnic Disparities in Crime and Criminal Justice in the United States.” Crime & Justice 21 (1): 311-­‐74. March 15: Housing Discrimination 7 Massey, D. and Garvey L. 2001. “Use of Black English and Racial Discrimination in Urban Housing Markets: New Methods and Findings.” Urban Affairs Review 36(4): 452-­‐69. Charles, C. 2003. “The Dynamics of Racial Residential Segregation.” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (1): 167-­‐207. March 17: Redlining & Policy Practices of Housing Discrimination Hernandez, J. 2009. “Redlining Revisited: Mortgage Lending Patterns in Sacramento 1930–2004.” International Journal of Urban & Regional Research 33 (2): 291-­‐313. Squires, G. 2003. “Racial Profiling, Insurance Style: Insurance Redlining and the Uneven Development of Metropolitan Areas.”Journal of Urban Affairs 25 (4): 391-­‐410. March 22: The Impact of Racism & Sexism on Health Outcomes McGibbon, E. & McPherson, C. 2011. “Applying Intersectionality & Complexity Theory to Address the Social Determinants of Women’s Health” Women's Health and Urban Life, 10(1): 59-­‐86. Bowleg, L. 2012. “The Problem With the Phrase Women and Minorities: Intersectionality—an Important Theoretical Framework for Public Health.” American Journal of Public Health 102 (7): 1267-­‐78. March 24: Intersectionality in the Immigration & Healthcare Systems Viruell-­‐Fuentes, E., Miranda, P. & Abdulhahim, S. 2012. “More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory and immigrant health.” Social Science & Medicine 75 (1): 2099-­‐2106. Gee, G. & Ford, C. 2011. “Structural Racism and Health Inequities: Old Issues, New Directions.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 8 (1): 115-­‐132 March 29: Class Identities & Perspectives Barker, Judith. 1996. “A White Working Class Perspective on Epistemology.” Race, Gender, and Class 4(1): 103-­‐118. Belkhir, Jean Ait. 1996. “Social Inequality and Race, Gender, Class: A Working Class Intellectual Perspective.” Race, Gender, and Class 4(1): 167-­‐194. March 31: Centering Sexuality 8 Purdie-­‐Vaughns, V. & Eibach, R. 2008. “Intersectional Invisibility: The Distinctive Advantages and Disadvantages of Multiple Subordinate-­‐Group Identities.” Sex Roles. 59 (5): 377-­‐391. Gamson, J. and Moon, D. 2004. “The Sociology of Sexualities: Queer and Beyond.” Annual Review of Sociology 30(1): 47-­‐64. April 5: Gender Disparities in Wealth Deere, C. & Doss, C. 2006. “The Gender Asset Gap: What do we know and why does it matter?” Feminist Economics 12 (1): 1-­‐50 Hogan, Richard and Carolyn C. Perrucci. 1998. “Producing & Reproducing Class & Status Differences: Racial and Gender Gaps in U.S. Employment & Retirement Income.” Social Problems. 45(4): 528-­‐549. PART III: IMPLICATIONS OF INTERSECTIONALITY **Class Conference** April 7: Indigenous Perspectives on Intersectionality Forbes, Jack D. 1997. “The Native Intellectual Tradition in Relation to Race, Gender, and Class.” Race, Class, and Gender 2(2): 49-­‐64. April 12: NO CLASSES April 14: Intersectional Perspectives on Working Class Women’s Political Activism Abramovitz, Mimi. 2001. “Learning from the History of Poor and Working-­‐Class Women’s Activism.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 577 (1): 118-­‐130. Naples, Nancy. 1991. “‘Just What Needed to Be Done’: The Political Practice of Women Community Workers in Low-­‐Income Neighborhoods.” Gender & Society 5 (1): 478-­‐494. April 19: Intersectionality for Social Change Naples, N. A. 1998. “Toward a Multiracial, Feminist Social-­‐Democratic Praxis: Lessons from Grassroots Warriors in the U.S. War on Poverty.” Social Politics 5(3): 286-­‐313. 9 Naples, N. 1992. “Activist Mothering: Cross Generational Continuity in the Community Work of Women From Low-­‐Income Urban Neighborhoods.” Gender & Society 6(3): 441-­‐ 463. April 21: #BlackLivesMatter, #AlllivesMatter? Teuscher, A. 2015. “The Inclusive Strength of #BlackLivesMatter.” The American Prospect Lassiter, J. 2015. “Internalizing Black Lives Matter: A Queer Project in Loving Blackness.” The Hampton Institute, Pp. 1 Casper, M. December, 2014. “Black Lives Matter / Black Life Matters: A Conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore.” The Feminist Wire, Pp. 1 Tometi, O. & Lenoir, G. 2015. “Black Lives Matter is Not a Civil Rights Movement.” Time Magazine April 26: NO CLASSES April 28: NO CLASSES FINAL EXAM on May 5 at 12 noon sharp. 10