The Electoral College

advertisement

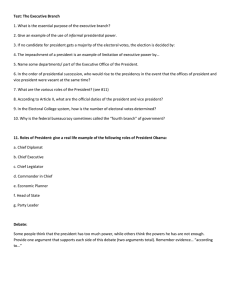

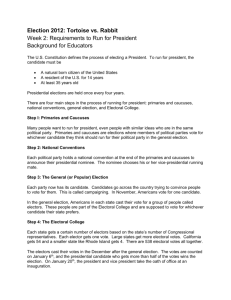

The Electoral College The Electoral College is a group of people who gather to cast their votes for the various presidential candidates (much like the delegates at the political party conventions). When we as Americans are casting our votes for the presidential candidates, we are actually casting our votes for electors, who will cast their votes for the candidates. Article II of the Constitution lists the specifics of the Electoral College. The Founding Fathers included the Electoral College as one of the famous "checks and balances" for two reasons: 1) to give states with small populations more of an equal weight in the presidential election and 2) they didn't trust the common man (Remember, women couldn't vote then.) to be able to make an informed decision on which candidate would make the best president. First of all, the same theory that created the U.S. Senate practice of giving two Senators to each state created the Electoral College. The large-population states had their populations reflected in the House of Representatives. New York and Pennsylvania, two of the states with the largest populations, had the highest number of members of the House of Representatives. But these two states still had only two senators, the exact same number that small-population states like Rhode Island and Delaware had. This was true as well in the Electoral College: Each state had just one vote, regardless of how many members of the House represented that state. So, the one vote that the state of New York cast would be decided by an initial vote of New York's Representatives. (If that initial vote was a tie, then that deadlock would have to be broken.) Secondly, when the Constitution was being written, not many people knew a whole lot about government, politics, or presidential elections. A large number of people were farmers or lived in rural areas, where they were far more concerned with making a living and providing for their families than they were with who was running for which office. Many of these "common people" could not read or write, either, and wouldn't be able to read a ballot in any case. Like it or not, the Founding Fathers thought that even if these "common people" could vote, they wouldn't necessarily make the best decision for who would make the best president. So, the Electoral College was born. Technically, the electors do not have to vote for anyone. The Constitution does not require them to do so. And throughout the history of presidential elections, some have indeed voted for someone else. But tradition holds that the electors vote for the candidate chosen by their state, and so the vast majority of electors do just that. The Electoral College meets a few weeks after the presidential election. Mostly, their meeting is a formality. When all the electoral votes are counted, the president with the most votes wins. In most cases, the candidate who wins the popular vote also wins in the Electoral College. However, this has not always been the case. The Election of 1800 The Election of 1824 The Election of 1876 The Election of 2000 The Election of 1800 In 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr, both members of the Democratic-Republican party, received 73 electoral votes. (Adams got 65.) How to break the tie? The Constitution provides for this, empowering the House of Representatives to choose the president through a direct popular vote. This was before the candidates were running for president and vice-president. The Founding Fathers assumed that voters would naturally vote this way; but in this instance, that was not what happened. This was the fourth presidential election in the young nation's history. George Washington had been elected unanimously for both of his terms, then retired. In his farewell address, he urged the political leaders of the time not to engage in party politics, for fear of dividing the nation. The political leaders of the time did not listen, however, and formed political parties that reflected their views. The two main political parties at this time were the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party. The leaders of the Federalist Party, which favored protection of the wealthy, were Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, and John Jay. The leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party, which favored protection of the common people, were Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe. Burr was also a Democratic-Republican. Jefferson was vice-president to Adams, who was elected in 1796 and ran for re-election in 1800. Many voters were fed up with Federalist policies in 1800 (especially after the passage and subsequent enforcement of the Alien and Sedition acts) and so voted for Jefferson and Burr. Trouble was, both candidates ended up with the same number of electoral votes. So into the House of Representatives the election went. It should also be noted here that Hamilton and Jefferson, as leaders of their respective political parties, were bitter enemies. They disagreed savagely on the role of government in people's lives and the role of the United States in the larger world. They were enemies across the political divide. The rift between Hamilton and Burr, however, was a personal one. For whatever reason, the two men detested each other personally, a scorn that went far beyond the political disagreements that Hamilton and Jefferson had. And so when Hamilton saw that Burr had a chance of becoming President, he jumped into the fray. Choosing to argue for the election of one political rival over another, Hamilton worked behind the scenes to ensure that Burr was not the new president. The House of Representatives eventually, on the 36th ballot, chose Jefferson. Burr became vice-president. The Election of 1824 The next challenge to the electoral process came in 1824. James Monroe, a wildly popular president, had retired after two terms, following the example of George Washington. Monroe was so popular that in his re-election bid of 1820, he won every single state and would have received a unanimous electoral vote if not for an elector who cast his vote in an effort to keep Washington as the only president to have been elected unanimously. In 1824, all of the candidates were members of the Democratic-Republican Party: John Quincy Adams, son of President John Adams, was a leading candidate this year. Secretary of State under Monroe, Adams also had a large amount of international experience, having been Minister to the Netherlands and Minister to Russia. He had the support of powerful people in the Northeast. Another leading candidate was war hero Andrew Jackson. Jackson was from Tennessee, a recently admitted state, and had the support of people in the West. Henry Clay was the author of the Missouri Compromise, Speaker of the House of Representatives, and was also immensely popular with people all over the country. William Crawford of Georgia also had a good bit of support, from Virginia, his birth state, and elsewhere in the country. When the votes were counted, Jackson had the most, 99. But he didn't have enough to win. The total number of electoral votes available at that time was 261. A candidate, therefore, needed 131 to win. Adams was second in the vote total, with 84. Crawford had 41, and Clay got 37. Since no candidate had receive a majority of electoral votes, it was back to the House of Representatives. Clay, as Speaker of the House, had control over the proceedings and, when it became clear that something had to be done, agreed to withdraw from the race if his supporters would instead support Adams. This wasn't about electoral votes anymore, however. Each state had one vote in the House of Representatives. The country had 24 states at the time, and 13 of them voted for Adams. Clay, in turn, was named Secretary of State. Jackson and his supporters, along with many other neutral observers, denounced this turn of events as a "corrupt bargain," but the votes were counted and the son of a president was in the White House. The Election of 1876 The third election decided not by the popular vote but by the Electoral College was that of 1876. By then, the concept of a popular vote was well established and the electoral vote had become a reflection of that popular vote. In 1876, however, that wasn't the case. The United States in 1876 was still healing from the wounds of the Civil War. Federal troops were still in Southern states, sometimes in large numbers, enforcing the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments. Reconstruction was still going on in a big way, and many people in the South resented what they saw as the continuation of an occupation by the victorious North. The two presidential terms of Ulysses S. Grant were marred by political scandal as well, and a constant them during the election campaigns was political honesty and restoring trust in government. By this time, also, the presence of many candidates for president in the general election was limited if not nonexistent. In this election, only two major candidates appeared. (As a historical footnote, 85-year-old Peter Cooper was the nominee of the National Greenback Party; he received no electoral votes.) The Democratic Party, the party of Andrew Jackson, had nominated as its nominee Samuel J. Tilden, the governor of New York. The Republican Party, meanwhile, relatively new to the political scene, had nominated the governor of Ohio, Rutherford B. Hayes. When the popular votes were counted, Tilden had the most, more than 280,000 more than Hayes. But he didn't have enough electoral votes to win. At that time, the total number of electoral votes was 369. Tilden had 184, one fewer than what he needed to win. Being one vote short was the same as being 100 votes short, however, because he still wasn't elected. Hayes, meanwhile, had 165. All he needed was 20 votes. And, conveniently for him, 20 electoral votes were in dispute. Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina still had Reconstruction governments. Oregon had one elector who was a postmaster. This was just the beginning of strange goings-on. The postmaster of Oregon, a Republican, was forbidden from voting because he worked for the federal government. His replacement was appointed by the governor of Oregon, who was a Democrat and who, naturally, appointed a Democrat in place of the Republican postmaster. Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were a bit more complex in that leaders of both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party reported vote totals. Not unexpectedly, the Democratic Party vote totals for these three states showed Tilden the winner and the Republican Party vote totals for those same three states showed Hayes the winner. What to do? The Constitution was silent on the matter. In desperation, Congress appointed a special commission to decide the election. The Electoral Commission had 15 members: 5 Representatives, 5 Senators, and 5 Supreme Court justices. Of these 15 members, 8 were Republican and 7 were Democrat. By a vote of 8-7, they decided to award all of the disputed votes to Hayes, giving him 185 electoral votes, exactly the number he needed to become president. It was not over, though. Congress still had to approve the commission's findings. Behind-the-scenes maneuvering resulted in approval of the 8-7 vote giving Hayes the presidency, in exchange for removing Federal troops from the South, a plan to spur industrialization in Southern states, and to make sure that a Democrat had a prominent part in the new (Republican) president's Cabinet. This long certification process went on for months, finally confirming Hayes as president just two days before Inauguration Day (which in those days was March 4). One of Hayes's first actions as president was to remove all remaining Federal troops from Southern states, leaving those states to work out Reconstruction issues on their own. The Election of 2000 The last election that needed to be decided by means other than the Electoral College took place very recently, in 2000. It all came down one state and that state's method of counting votes. The state in question was Florida, and the election was eventually decided by the Supreme Court. The Democratic Party's nominee was Vice-President Al Gore. A presidential candidate himself back in 1988, Gore had served as vice-president for both of President Bill Clinton's terms. As such, he was both a champion of Clinton's successes and a reflection of his failures. The Republican Party's nominee was George W. Bush, governor of Texas and son of former President George Bush. he campaigned on a platform of a strong national defense and an end to questionable ethics in the White House. The election was hotly contested, and many states went down to the wire, being decided by only a handful of votes. The one state that seemed to be flip-flopping as Election Day turned into Election Night was Florida. In the end, Gore won the popular vote, by nearly 540,000 votes. But he didn't win the electoral vote. The vote was so close in Florida that a recount was necessary under federal law. During the recount, election officials discovered a series of regularities involving what made an official ballot. Computer recounts gave Bush a 327-vote lead for the entire state, which in all case 6 million votes. The difference between the two candidates's totals was so close, though, that Florida officials ordered a recount by hand. A series of legal maneuvers followed, including the following: Florida Secretary of State Kathleen Harris sets a deadline for the recount Election officials in counties where vote totals were disputed worked as hard as they could to count ballots before the deadline The Florida Supreme Court extends Harris's deadline but also weighs in in favor of as much recounting as can possibly be done by that new deadline The U.S. Supreme Court orders a halt to the recount and rules that the most recent vote total, which favored Bush, be certified as official. As a result, all recounts of votes in Florida were stopped Bush was ruled to have won Florida by 930 votes and then awarded Florida's electoral votes, giving him 271, one more than he needed to win. Gore had 266. It was the closest Electoral College election since 1876.