The Economic Impact of Naturalization on Immigrants and Cities

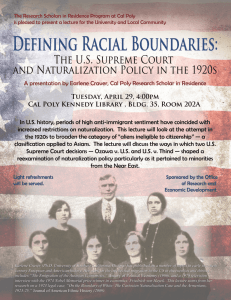

advertisement