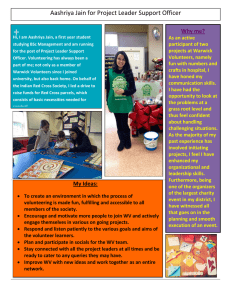

Volonteurope reports on:

advertisement