Colonial Waterbirds in the Great Lakes as Indicators of Toxic... Dr. Keith Grasman, Alaina Mahn, David Bouma, Jenna Van Bruggen

advertisement

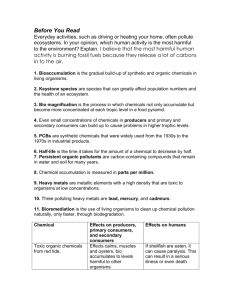

Colonial Waterbirds in the Great Lakes as Indicators of Toxic Pollution Dr. Keith Grasman, Alaina Mahn, David Bouma, Jenna Van Bruggen The Great Lakes is the largest system of freshwater lakes in the world, and many people depend on them to be kept clean and uncontaminated. Regardless, many harmful organochlorines like dioxins and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls) were released into the Great Lakes during the late 1800s and 1900s. PCBs function as flame retardants (often in electrical transformers), adhesives, inks, plasticizers, pesticide extenders, and many other products. PCBs were banned in 1979, but due to their unique chemical makeup, PCBs break down very slowly causing them to be a persistent problem. While some work was done in the 1980s to clean up the most contaminated areas, many PCBs remained in the environment. PCBs, one of many organochlorines, have been found to cause a variety of problems in wildlife and humans and accumulate in the sediments and water. Once in the environment, they enter into the Great Lakes food chain, with each member of the chain becoming more contaminated than the previous. Fish-eating birds are a good indicator for levels of pollution as they are some of the highest members in the food chain and are therefore some of the most highly contaminated species in the ecosystem. The birds then pass these contaminants on to their offspring, resulting in deformities and suppression of the chicks’ immune systems. This study looked at the chicks in herring gull and Caspian tern colonies in an attempt to monitor organochlorines and help determine the health of the Great Lakes as a whole. Sites like Saginaw Bay and River Raisin have high organochlorine contaminant levels, and they have consequently been named Areas of Concern by the International Joint Commission. Other sites, like the North Channel in Lake Huron, have less organochlorine pollution, making them good reference sites for our study. In 2014 Grand Traverse Bay was added to this study due to an unusual combination of contaminants; a high level of dioxin toxic equivalents and a relatively low concentration of PCBs. At each site a variety of data was collected: basic body measurements; surveys of the percentage of chicks that survive to three weeks of age; chemical tests to determine the concentrations of organochlorines as well as contaminants of emerging concern found in eggs; and immune function tests which evaluate inflammatory responses, antibody production, and white blood cell activity in lab cultures. Since the 1990s Dr. Keith Grasman and his lab have seen immune problems in many colonies living in polluted sites and continue to monitor the extent of these problems each year. In the past five years, a decreased immune response and lower growth rates, as well as impairments to reproduction in Saginaw Bay and River Raisin continues to be seen. A herring gull colony in Grand Traverse Bay also showed impaired immune responses and low growth rate. By indicating if the problems are improving or becoming worse, the government, management agencies, and individuals can make informed decisions about how these sites should be handled. For example, a decrease in bird health could indicate a new source of pollution, while if the problem begins to disappear these sites could be removed from the list of Areas of Concern. Furthermore, by having this information and making the public aware of it, individuals can make informed decisions on whether or not to eat fish caught in these areas and in which other ways they wish to interact with the lakes. This research has allowed us to gain valuable field and lab experience. We now appreciate a shower at the end of a long day and are wary of birds flying overhead. On a more serious note, the research has kindled an awareness of the disturbing consequences of humankind's organochlorine useage and their implications for the environment.