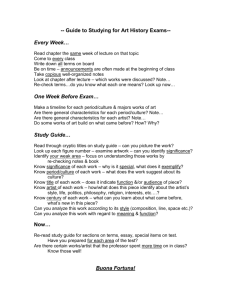

Document 14393849

advertisement

TOP: William Powhida, Griftopia, 2011. Archival inkjet print, 8 x 4 feet. LEFT: Kyle Fletcher, Fiscal Cliff Notes No. 1, 2013. Inkjet on newsprint, 18 x 27 inches. RIGHT: Kate Bingaman-Burt, JoAnn, 2013. Thermal print, dimensions variable. commercial signage; reminding us that outside of the exploding high-end subset of the market so often fetishized and condemned, the vast majority of artists and art are part of a bigger stagnating and shrinking middle market that parallels our economic times writ large. The show begins with an opening performance of social exchange, Safe $ Secure, in which three ostensible security guards’ scripted vigilance gradually gives way to improvisation with the audience. The performance, which acts to embody and open up questions about the relationships, particularly involving power and authority, formed under particular kinds of security economics, also pokes wryly at one of the most foundational conceptions in modern economics: that markets automatically refine human instincts into positive social relationships. Famously, Adam Smith’s classic explanation that the butcher, baker, and candlestick maker work out of self-interest alone, but in doing so create a better society for all, has now been taken up by neoclassical economics as a commonplace argument that the structure of capitalism as such creates the conditions for rewarding social ends. Safe $ Secure, in contrast, questions the sorts of roles we take on in late capitalism when all relationships are increasingly mediated by market logics—and the threat of violence underlying them. is a multi-faceted investigation of economic, commercial and aesthetic value. Featuring artists from across the country working in a variety of media, this formal and conceptual cross section unpacks the ever-changing relationship between value, wealth, and worth in contemporary culture. FEATURING The current prolific circulation of articles and mass market books about the increasingly inaccessible, exorbitant, and often fly-bynight high-end art market seems both deeply ironic and a perfectly logical entailment about Americans’ anxieties surrounding value and worth now. The art world is schizophrenically both elitist and democratic in its rhetorics: both a public cultural good and a lucrative private investment for hyper-rich patrons whose acquisition styles increasingly recall Renaissance art economics. The deep texturing of art as both a commodity and a symbolically transcendent intellectual object offers coy oscillations between appeals to price and pricelessness that offer halfanswers to the serious questions we’re facing about what value itself is now—a telling fable about the ever-loosening relationships between value, price, and meaning. How to tread the territory of contemporary art economics without submitting to either gossipy breathlessness at the scandal of the market’s informalities or portentous and pretentious theoretical condemnations about neoliberalism (one thinks of Dave Hickey’s comment that to call the market corrupt under our cultural conditions is like saying that the cancer patient has a hangnail)? Curator Steve Juras’ answer is twofold: first, to humor the subject, both through humor as drollness in style and through humoring as accommodating and taking up the logics of the market in the very form of the exhibition. Second, in critiques regarding the slippage between art and commodity, rather than focusing on the common analogies made between the high-end art market and luxury goods, the artists in Market Value: Examining Wealth and Worth take as their points of reference the other end of the commodity markets: gift shops, design products, and Kate Bingaman-Burt Alice Bradshaw Angela Finney-Hoffman Kyle Fletcher Jason Frohlichstein Mitch Hollingsworth Mark Merrit Derek Moore Steve Moore William Napperson Ches Perry Chad Person Jason Polan William Powhida The contrast between the rent-a-guard trope—a ubiquitous marker of privatization­—and the college gallery setting also destabilizes common understanding of the roles of different institutions in the market. Kyle Fletcher and Derek Moore’s creation of Upper Crust Auction House, an auction website for the show, further calls into question the relationship between the outward sanctity of the college from market forces and frames the space as both a literal and metaphorical marketplace. We are now used to the auction house supplanting the curator, the collector as critic, with financial firms and institutions bypassing the figures that used to be called on to turn symbolic capital and culture capital into real capital—particularly the critic. Within this sea change, where the perceptions and judgments of critics and gallerists are replaced by market logics of investment and risk-taking, the condemnations of financial logics by criticturned-artist William Powhida feel particularly germane. Powhida’s meticulous infographic tracing the culpable parties in the 2008 financial crisis provocatively mirror handwritten essays that explain in heartbreaking detail step-by-step directions to manipulating art markets. Investment as meaning-making is only the strongest case of another economic motif that underlies the show: money as a kind of language that speaks about itself. Two artists use the symbolism of price and the material of currency themselves as mediums. Chad Person’s typographic inscriptions ABOVE: Jason Frohlichstein, The Various, 2013 (publication). Inkjet on newsprint (edition of 1000), 11 x 14 inches. LEFT: Chad Person, Fast and Loose, 2011. U.S. currency on canvas, 16 x 16 inches. BOTTOM LEFT: Jason Polan, Three Dollar $2 Bill, 2013. Risograph printed in red, signed in pencil on reverse, open edition, 8.5 x 5.5 inches. in which symbolic value surpasses the literal worth of the art object through information asymmetry and perceived scarcity, points out that this tendency is endemic to markets at large. Continuing the theme of the artist as a value-adder, we might think of Isabelle Graw’s insights into the artist’s personhood as a product, and the artist as a kind of exceptional being whose autobiography is the source of worth in the work. Kate BingamanBurt’s hand-drawn receipts provide a counterpoint to this idea, where the autobiography of the artist provides a conduit between personal value and commerce. Angela Finney-Hoffman’s work explores a parallel conception of value-adding by the artist with VS., a found ping-pong table that the artist, a professional interior designer, altered so that plywood covers one half, in contrast to elegant embroidered canvas on the opposite surface. That the game is still fully functional attests to the fluidity of the back-and-forth exchange between worth and value in art market rhetoric. on canvas express clichés—know when to fold em, fast and loose—with lettering that consists of minute fragments of currency. Person subtly undermines the economic notion that substantive information is embedded in prices; we might think of Hayek’s argument that the real meaning of price is just shorthand for relationships, a “mechanism for communicating information” that coordinates “the separate actions of different people.” Jason Polan’s stack of $2 bill prints also point to the fictions created through pricing money; the bill, which is in fact not out of circulation, is not worth more than its face value, despite myths to the contrary. Polan’s playful critique of “value adding” in the art market, The heart of the exhibition lies in the tension Finney-Hoffman embodies as an artist who also works in fields seen as more commoditized: interior decoration in her case. For artist and designer Jason Frohlichstein, the focus of critique is design as an ephemeral product, quickly consumed and often never distributed. His installation consisting of stacks of newspapers distributed for free offers a substantive for those who experience it as an intellectual object, and a profane material good that can be sold, marketed, and collected. As simple as this duality is, the parallels drawn between art markets and other markets continue to be striking and enlightening, both of the way we fetishize both art and of the role of cultural capital in all markets. The fear of the commoditization of art, as Pop art, conceptualism, and photographic documentation have steadily marched contemporary art away from exceptionality and into a world of substitutes and what a Thomas Crow editorial from April 2008’s Artforum, just before the financial collapse, calls “principle of equivalence.” institutional critique of the consumption of art itself as a form of mass media. Fletcher continues this direct confrontation of the consumption of art in his Fiscal Cliff Notes poster series, which presents a command to the viewer not to buy the work, both inviting and then resisting the investment of both our attention and money into the piece. Several artists in the show take up this theme, but rather than referencing the obvious luxury-goods market, they draw connections between art and more “lowly” commodities, highlighting the role of the middle market for art, which is feeling the effects of the current economy in a disproportional way to the still-exploding high-end subset of the market. Steve Moore and professional sign painter Ches Perry’s collaborative aphorisms combine Perry’s commercial signage lettering with Moore’s hollow, ad-speak truisms about value—and, placed in the front windows of the gallery, both frame the show and recall mom-and-pop shop storefronts, yet another victim of the financial crisis. Alice Bradshaw’s souvenir items—limited edition badges, bags, puzzles, and cups-- recall gifts shops from museums and other global tourist attractions. The images they present are selected archival images from the artist’s Museum of Contemporary Rubbish, an online photographic archive of detritus and discarded material culture. The final work draws on the running theme of the artist as injector of aesthetic value and the imminent collapse between, and endless recycling of, art and devalued commercial objects. Art has always been a special kind of commodity, both sacred in its symbolic aesthetic elements The public imagination of the relationship between price and pricelessness in art ultimately allows art TOP LEFT: Angela Finney-Hoffman, VS., 2013. Concept sketch for site-specific installation. TOP RIGHT: Alice Bradshaw, Museum of Contemporary Rubbish Jigsaw, Item #0451 (takeaway box, UK). Card backed lustre print, 12 x 8 inches. ABOVE: Steve Moore & Ches Perry, Value the Worthless on Purpose, 2013. Sign paint on butcher paper, 24 x 36 inches. to be a proxy for value itself. As Rachel Cohen points out, “we have long entrusted the task of representing our ideas of value to members of two professions that might seem to have little in common: banking and art.” The wild speculation, idiosyncratic regulation, and lack of transparency that marks both the current financial ecosystem and art markets betrays the myths and fallacies of openness and structural fairness involved in both: there is nothing “free” about the free markets we now inhabit. The slipperiness of wealth and worth is only more obvious in the semi-autonomous role of contemporary art in global markets, in its unique position in the global economy. The game of coming together to come up with prices is only more obviously informal in the art market. Other places for assigning value and price are just as arbitrary, with people coming together and deciding what something is worth, oftentimes with disregard to actual cost; we might think of externalities involved in environmental damage, for example factory farming and the real cost of a $.99 hamburger. Market Value: Examining Wealth and Worth offers only one of endless inlets into a critique of contemporary economics, where the deepest problem is the faith we put in prices of any kind as a way of valuing the world, and where there is serious work to be done in making the idea of value and money congruent at a moment in which they are strikingly unaligned. Monica Westin is a PhD student and University Fellow, focusing on rhetorical theory and its intersections with historical debates in philosophical aesthetics and critical digital theory, at the University of Illinois in Chicago’s English Studies department. She teaches in the Writing, Rhetoric, and Discourse Department and the New Media Studies graduate program at DePaul University. Her criticism and journalism has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, The Believer, BOMBblog, and Art21, among other places. A+D ar t + design AVERILL AND BERNARD LEVITON GALLERY HOURS A+D GALLERY TUESDAY – SATURDAY 619 SOUTH WABASH AVENUE 11AM – 5PM CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60605 312 369 8687 THURSDAY COLUM.EDU/ADGALLERY 11AM – 8PM This exhibition is sponsored by the Art + Design Department at Columbia College Chicago and Anchor Graphics. This exhibition is partially supported by an Illinois Arts Council Grant, a state agency. ABOVE: Mark Merrit, Mitch Hollingsworth, and William Napperson, Safe $ Secure, 2013. Performance. Photography by Joshua Longbrake