Original Article

Indicated and Non-Indicated Preterm Delivery in Twin

Gestations: Impact on Neonatal Outcome and Cost

John P. Elliott, MD

Niki B. Istwan, RN, BS

Ann Collins, RNC, BSN

Debbie Rhea, MPH

Gary Stanziano, MD

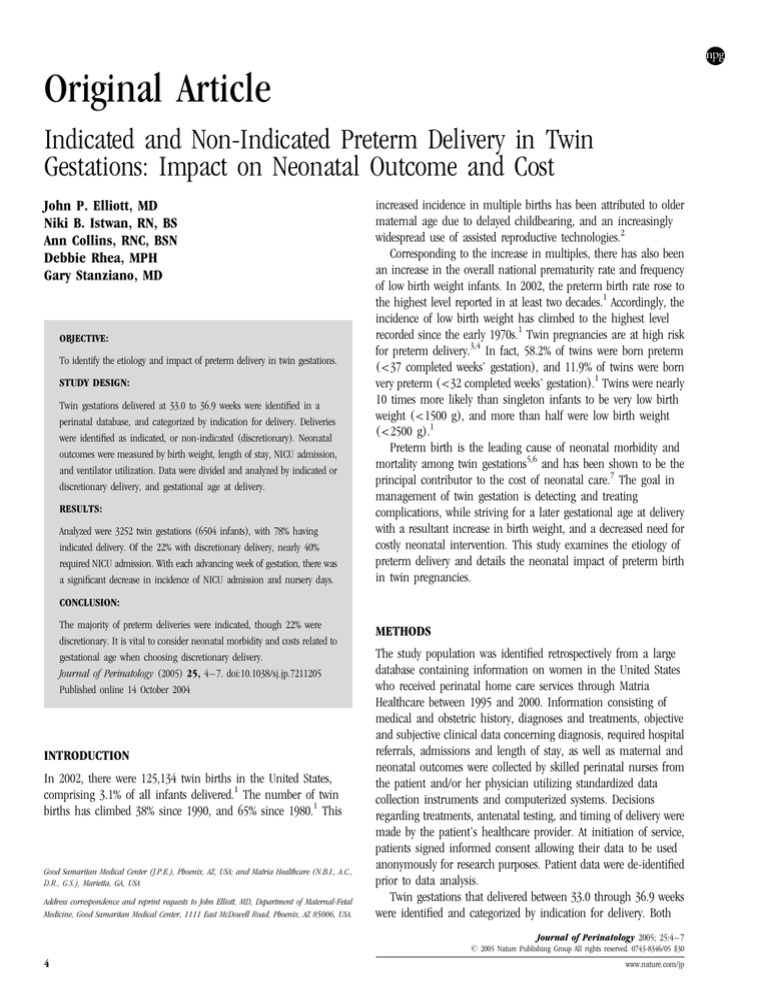

OBJECTIVE:

To identify the etiology and impact of preterm delivery in twin gestations.

STUDY DESIGN:

Twin gestations delivered at 33.0 to 36.9 weeks were identified in a

perinatal database, and categorized by indication for delivery. Deliveries

were identified as indicated, or non-indicated (discretionary). Neonatal

outcomes were measured by birth weight, length of stay, NICU admission,

and ventilator utilization. Data were divided and analyzed by indicated or

discretionary delivery, and gestational age at delivery.

RESULTS:

Analyzed were 3252 twin gestations (6504 infants), with 78% having

indicated delivery. Of the 22% with discretionary delivery, nearly 40%

required NICU admission. With each advancing week of gestation, there was

a significant decrease in incidence of NICU admission and nursery days.

increased incidence in multiple births has been attributed to older

maternal age due to delayed childbearing, and an increasingly

widespread use of assisted reproductive technologies.2

Corresponding to the increase in multiples, there has also been

an increase in the overall national prematurity rate and frequency

of low birth weight infants. In 2002, the preterm birth rate rose to

the highest level reported in at least two decades.1 Accordingly, the

incidence of low birth weight has climbed to the highest level

recorded since the early 1970s.1 Twin pregnancies are at high risk

for preterm delivery.3,4 In fact, 58.2% of twins were born preterm

(<37 completed weeks’ gestation), and 11.9% of twins were born

very preterm (<32 completed weeks’ gestation).1 Twins were nearly

10 times more likely than singleton infants to be very low birth

weight (<1500 g), and more than half were low birth weight

(<2500 g).1

Preterm birth is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and

mortality among twin gestations5,6 and has been shown to be the

principal contributor to the cost of neonatal care.7 The goal in

management of twin gestation is detecting and treating

complications, while striving for a later gestational age at delivery

with a resultant increase in birth weight, and a decreased need for

costly neonatal intervention. This study examines the etiology of

preterm delivery and details the neonatal impact of preterm birth

in twin pregnancies.

CONCLUSION:

The majority of preterm deliveries were indicated, though 22% were

discretionary. It is vital to consider neonatal morbidity and costs related to

gestational age when choosing discretionary delivery.

Journal of Perinatology (2005) 25, 4–7. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211205

Published online 14 October 2004

INTRODUCTION

In 2002, there were 125,134 twin births in the United States,

comprising 3.1% of all infants delivered.1 The number of twin

births has climbed 38% since 1990, and 65% since 1980.1 This

Good Samaritan Medical Center (J.P.E.), Phoenix, AZ, USA; and Matria Healthcare (N.B.I., A.C.,

D.R., G.S.), Marietta, GA, USA

Address correspondence and reprint requests to John Elliott, MD, Department of Maternal-Fetal

Medicine, Good Samaritan Medical Center, 1111 East McDowell Road, Phoenix, AZ 85006, USA.

METHODS

The study population was identified retrospectively from a large

database containing information on women in the United States

who received perinatal home care services through Matria

Healthcare between 1995 and 2000. Information consisting of

medical and obstetric history, diagnoses and treatments, objective

and subjective clinical data concerning diagnosis, required hospital

referrals, admissions and length of stay, as well as maternal and

neonatal outcomes were collected by skilled perinatal nurses from

the patient and/or her physician utilizing standardized data

collection instruments and computerized systems. Decisions

regarding treatments, antenatal testing, and timing of delivery were

made by the patient’s healthcare provider. At initiation of service,

patients signed informed consent allowing their data to be used

anonymously for research purposes. Patient data were de-identified

prior to data analysis.

Twin gestations that delivered between 33.0 through 36.9 weeks

were identified and categorized by indication for delivery. Both

Journal of Perinatology 2005; 25:4–7

r 2005 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved. 0743-8346/05 $30

4

www.nature.com/jp

Etiology and Impact of Preterm Delivery

labor onset and conditions present at delivery were considered in

determining if a delivery was indicated or non-indicated

(discretionary). Deliveries were identified as being indicated if labor

was either spontaneous, induced, or did not occur, and one or

more of the following conditions were present: preterm labor;

preterm premature rupture of membranes (PROM), maternal

indications (including pregnancy-induced hypertension, bleeding,

infection and diabetes); or fetal indications (including nonreassuring fetal surveillance, suspected intrauterine growth

restriction, or fetal demise). Deliveries were identified as being nonindicated (discretionary) if labor was induced or did not occur,

preterm PROM, maternal or fetal indications were not present, and

the delivery reason was recorded as elective in the outpatient

medical record. Discretionary delivery included patients without

documentation of idiopathic, maternal, or fetal indications, having

induced labor or scheduled cesarean delivery. Records unable to be

clearly categorized were eliminated from analysis. Data regarding

maternal demographics, history of previous preterm deliveries,

cerclage and use of tocolysis were likewise identified.

Neonatal outcome was measured by gestational age at delivery,

birth weight, length of nursery stay, incidence of neonatal intensive

care unit (NICU) admission, and need for mechanical ventilation.

Data were divided and analyzed by indicated or discretionary (nonindicated) delivery and week delivered using one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) with multiple pairwise comparisons

(Bonferroni), independent Student’s t, Kruskal–Wallis H, Mann–

Whitney U, and Fisher exact test statistics. An alpha level of 0.05

was used with two-sided p-values reported.

RESULTS

There were 3252 twin gestations (6504 infants) with delivery

between 33.0 and 36.9 weeks categorized by reason for preterm

delivery. A total of 2536 women (78.0%) delivered preterm due to

maternal and/or fetal indications while 716 (22.0%) had

discretionary preterm delivery. Almost two-thirds (65.1%) of

indicated deliveries were related to preterm labor, 18.6% were due

to PROM, 13.4% due to maternal indications, and 2.8% for fetal

indications. There were 13 stillborn infants in the indicated delivery

group. Assessment of fetal lung maturity was documented in only

66 of 716 patients (9.2%) having discretionary delivery. The mean

maternal age of the study population was 30.0±5.8 years, with

21.9% being of advanced maternal age; 6.5% were smokers, 86.0%

were married, and 47.9% were nulliparous. Overall, 11.3% of

women had a history of previous preterm delivery, and 6.4% had a

cerclage with this pregnancy. Oral or subcutaneous tocolysis was

prescribed to 81.6% of the study population. Maternal

characteristics are compared between delivery groups in Table 1.

Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes are presented in Table 2.

Women with discretionary delivery were more likely to have a

Journal of Perinatology 2005; 25:4–7

Elliott et al.

Table 1 Maternal Characteristics

Characteristic

Indicated

delivery,

n ¼ 2536

Discretionary

delivery,

n ¼ 716

p-value

Maternal age (years)

Z35 years

Smoker

Unmarried

Nulliparous

Cerclage

Previous preterm delivery

Tocolysis

29.7±5.8

20.3%

6.7%

15.1%

47.9%

6.0%

11.6%

82.5%

31.1±5.7

27.7%

5.7%

9.9%

47.9%

7.8%

10.5%

78.8%

<0.001

<0.001

0.390

<0.001

1.000

0.083

0.424

0.029

Data presented as mean±SD, or percentage as indicated.

Table 2 Pregnancy and Neonatal Outcome

GA at delivery

Cesarean delivery

Birth weight, g

NICU admission

Mechanical ventilation

Total nursery days

Indicated

delivery,

n ¼ 5072

Discretionary

delivery,

n ¼ 1432

p-value

35.3±1.1

48.5%

2325±403

44.5%

5.8%

7.2±9.1

35.5±1.0

76.8%

2370±411

39.3%

5.0%

6.9±8.4

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

0.329

0.475

Data presented as mean±SD, or percentage as indicated.

cesarean delivery, and almost 40% of infants required NICU

admission. Women with discretionary delivery had a 36.8%

increased rate of cesarean delivery. In nulliparous only, the

incidence of cesarean delivery for those with indicated delivery was

49% versus 79% in women with discretionary delivery, p<0.001.

Overall, infants with discretionary delivery had similar nursery

lengths of stay when compared to the indicated delivery group.

To assess the impact of gestational age at delivery, we compared

neonatal outcomes by delivery week (Table 3). With each

advancing week of gestation there was a significant increase in

birth weight, with a corresponding decrease in nursery length of

stay, NICU admission, and utilization of assisted ventilation

(p<0.001). These trends were also observed among infants with

discretionary delivery. We observed a 44% decrease in the

percentage of NICU admissions when comparing infants with

discretionary delivery at 34 weeks with those delivered at 36 weeks

(65.2 versus 21.2%, respectively, p<0.001) and a nearly 50%

decrease in mean nursery days (8.3±6.6 versus 4.5±5.3 days,

p<0.001). With each advancing week of gestation, neonates with

discretionary delivery experienced decreased length of stay, NICU

admissions and NICU days, as well as decreased need for assisted

ventilation (data not shown).

5

Elliott et al.

Etiology and Impact of Preterm Delivery

Table 3 Neonatal Outcome by Gestational Age at Delivery

Birth weight, g

Cesarean delivery

Nursery LOS

NICU admission

Ventilator use

33 weeks, n ¼ 874

34 weeks, n ¼ 1342

35 weeks, n ¼ 1820

36 weeks, n ¼ 2468

p-value

1974±353

61.1%

15.4±11.5

83.5%

10.8%

2187±360

56.6%1

9.1±7.4

66.4%

8.3%

2349±348

55.7%1

5.9±10.2

38.2%

5.0%1,2

2533±362

50.6%1,2,3

4.1±4.4

20.5%

2.7%1,2,3

<0.0014

<0.001

<0.0014

<0.0014

<0.001

Data presented as mean±SD, or percentage as indicated. LOS ¼ Length of stay.

p<0.05 versus 133; 234; 335.

4

All pairwise differences p<0.05.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the etiology of preterm delivery among

twin gestations, and its impact on neonatal outcome. While the

majority of preterm deliveries in this population were attributed to

maternal or fetal indications, there was a relatively high incidence

of deliveries (22%) classified as discretionary. Our study

demonstrates that with each advancing week of gestation there was

increased birth weight, a decreased incidence of NICU admission,

nursery length of stay, and decreased utilization of mechanical

ventilation, regardless of indicated or discretionary delivery.

Our results are comparable with several previous studies. Büscher

et al.4 studied twin deliveries and found a difference in mean birth

weight for neonates delivered at Z37 weeks’ gestation versus infants

delivered between 34.0 and 36.9 weeks. Nearly 70% of twin neonates

delivered between 34.0 and 36.9 weeks were admitted to the NICU.4

Other studies also link a decrease in gestational age at delivery to

increased NICU admission and length of stay.8–10 In a study over a

10-year period of more than 8000 twin pairs, it was discovered that

significantly higher perinatal morbidity and mortality rates were

associated with delivery at r35 weeks’ gestation.10 Undoubtedly,

prematurity is correlated to low birth weight, NICU admission and

greater lengths of stay. These factors have a tremendous emotional

and financial impact on the parents of these babies. In a case–

control study of preterm twins versus singletons, Luke et al.7

discovered that increased medical costs are a factor of prematurity,

not plurality. Families affected by preterm birth often suffer

emotional problems, and ongoing parenting disorders are common.11

Some studies have suggested that it is prudent to intervene in

twin pregnancies at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestation, and that due to an

increased risk of mortality and morbidity, twin pregnancies should

not continue beyond 39 weeks’ gestation.10,12 While previous

authors have shown that optimal pregnancy outcomes occur

earlier in twin versus singleton gestations,12 there are no data to

support preterm intervention when there is no maternal or fetal

indication necessitating delivery. The preterm birth rate in the

United States remains unacceptably high. Increasing rates of

preterm birth have been associated with an escalating incidence of

labor induction or primary cesarean delivery prior to 37 weeks’

gestation.8,13 In a study examining trends in preterm deliveries of

6

twins by Joseph et al.,8 a 14% increase in the frequency of preterm

labor induction between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestation was identified;

however, no single indication was recognized as the underlying

cause of the increased frequency of preterm labor induction among

twins. A study by Kogen et al.13 related higher rates of preterm

delivery among twins to an increase in medical intervention and

utilization of intensive prenatal care.

Twin pregnancies are at risk for preterm delivery whether due to

spontaneous preterm labor, or other maternal or fetal

complications. However, 22% of preterm deliveries in our study

were discretionary (documented as elective without any indication

of acute maternal or fetal complications). Cesarean delivery

occurred at a significantly higher rate in women with discretionary

versus indicated delivery. Almost two-thirds of infants with

discretionary delivery were low birth weight, and nearly 40% were

admitted to the NICU. These results indicate that preterm

discretionary delivery of twins is associated with substantial

increased risk of both maternal and neonatal morbidity and cost.

The goal in management of a twin gestation is detecting and

treating complications, while striving for a later gestational age at

delivery with a resultant increase in birth weight, and a decreased

need for intensive neonatal intervention. Our study demonstrates

that the majority of preterm deliveries are indicated; however, one

in five preterm deliveries were discretionary. A potential limitation

in our study is that among records counted as discretionary

delivery, a true indication for delivery might have existed but was

not captured by the questions asked during the data collection

process. Nevertheless, the data support our findings that preterm

delivery among twins, for whatever cause, has costly ramifications,

whether it is increased maternal or neonatal morbidity, financial

expense, or emotional burden. Therefore, it is vital for the healthcare provider to consider these issues related to gestational age in

order to optimize pregnancy outcome when considering

discretionary delivery.

References

1. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Munson ML.

Births: Final Data for 2002 National Vital Statistics Reports, Vol.52, No.10.

Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2003.

Journal of Perinatology 2005; 25:4–7

Etiology and Impact of Preterm Delivery

2. Lam F, Bergauer NK, Jacques D, Coleman SK, Stanziano GJ. Clinical and

cost-effectiveness of continuous subcutaneous terbutaline versus oral

tocolytics for treatment of recurrent preterm labor in twin gestations.

J Perinatol 2001;21:444–50.

3. Gardner MO, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Tucker JM, Nelson KG, Copper RL.

The origin and outcome of preterm twin pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol

1995;85:553–7.

4. Büscher U, Horstkamp B, Wessel J, Chen FCK, Dudenhausen JW. Frequency

and significance of preterm delivery in twin pregnancies. Int J Gynaecol

Obstet 2000;69:1–7.

5. Knuppel RA, Lake MF, Watson DL, et al. Preventing preterm birth in twin

gestation: home uterine activity monitoring and perinatal nursing support.

Obstet Gynecol 1990;76:24S–7S.

6. Roberts WE, Morrison JC. Has the use of home monitors, fetal fibronectin,

and measurement of cervical length helped predict labor and/or prevent

preterm delivery in twins? Clin Obstet Gynecol 1998;41:95–102.

7. Luke B, Bigger HR, Leurgans S, Sietsema D. The cost of prematurity: a case–

control study of twins versus singletons. Am J Public Health 1996;86:809–14.

Journal of Perinatology 2005; 25:4–7

Elliott et al.

8. Joseph KS, Allen AC, Dodds L, Vincer MJ, Armson BA. Causes and

consequences of recent increases in preterm birth among twins. Obstet

Gynecol 2001;98:57–64.

9. Dyson DC, Crites YM, Ray DA, Armstrong MA. Prevention of preterm birth in

high-risk patients: the role of education and provider contact versus home

uterine monitoring. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:756–62.

10. Hartley RS, Emanuel I, Hitti J. Perinatal mortality and neonatal

morbidity rates among twin pairs at different gestational ages: optimal

delivery timing at 37 to 38 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2001;184:451–8.

11. Ladden M. The impact of preterm birth on the family and society:

Part 1: psychologic sequelae of preterm birth. Pediatr Nurs 1990;16:

515–8.

12. Warner BB, Kiely JL, Donovan EF. Multiple births and outcome. Clin

Perinatol 2000;27(2):347–61.

13. Kogen MD, Alexander GR, Kotelchuck M, et al. Trends in twin birth

outcomes and prenatal care utilization in the United States, 1981–1997.

JAMA 2000;283:335–41.

7