Journal of Perinatology (2006) 26, 3–10

r 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved. 0743-8346/06 $30

www.nature.com/jp

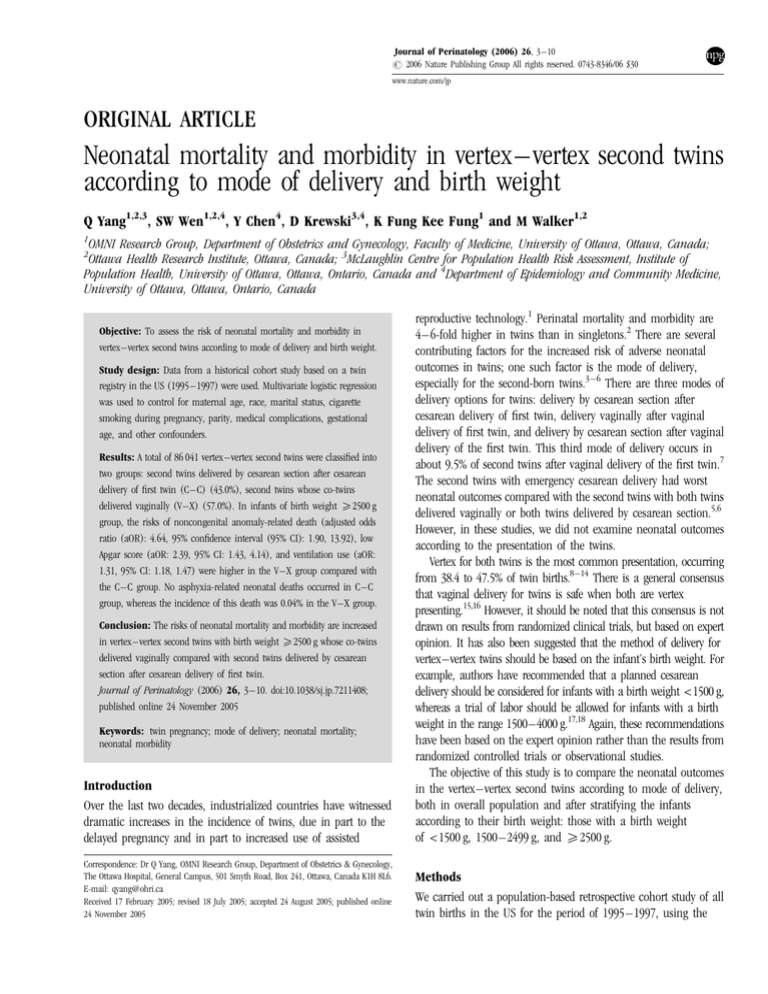

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

according to mode of delivery and birth weight

Q Yang1,2,3, SW Wen1,2,4, Y Chen4, D Krewski3,4, K Fung Kee Fung1 and M Walker1,2

1

OMNI Research Group, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada;

Ottawa Health Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; 3McLaughlin Centre for Population Health Risk Assessment, Institute of

Population Health, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada and 4Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine,

University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

2

Introduction

Over the last two decades, industrialized countries have witnessed

dramatic increases in the incidence of twins, due in part to the

delayed pregnancy and in part to increased use of assisted

reproductive technology.1 Perinatal mortality and morbidity are

4–6-fold higher in twins than in singletons.2 There are several

contributing factors for the increased risk of adverse neonatal

outcomes in twins; one such factor is the mode of delivery,

especially for the second-born twins.3–6 There are three modes of

delivery options for twins: delivery by cesarean section after

cesarean delivery of first twin, delivery vaginally after vaginal

delivery of first twin, and delivery by cesarean section after vaginal

delivery of the first twin. This third mode of delivery occurs in

about 9.5% of second twins after vaginal delivery of the first twin.7

The second twins with emergency cesarean delivery had worst

neonatal outcomes compared with the second twins with both twins

delivered vaginally or both twins delivered by cesarean section.5,6

However, in these studies, we did not examine neonatal outcomes

according to the presentation of the twins.

Vertex for both twins is the most common presentation, occurring

from 38.4 to 47.5% of twin births.8–14 There is a general consensus

that vaginal delivery for twins is safe when both are vertex

presenting.15,16 However, it should be noted that this consensus is not

drawn on results from randomized clinical trials, but based on expert

opinion. It has also been suggested that the method of delivery for

vertex–vertex twins should be based on the infant’s birth weight. For

example, authors have recommended that a planned cesarean

delivery should be considered for infants with a birth weight <1500 g,

whereas a trial of labor should be allowed for infants with a birth

weight in the range 1500–4000 g.17,18 Again, these recommendations

have been based on the expert opinion rather than the results from

randomized controlled trials or observational studies.

The objective of this study is to compare the neonatal outcomes

in the vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery,

both in overall population and after stratifying the infants

according to their birth weight: those with a birth weight

of <1500 g, 1500–2499 g, and X2500 g.

Correspondence: Dr Q Yang, OMNI Research Group, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology,

The Ottawa Hospital, General Campus, 501 Smyth Road, Box 241, Ottawa, Canada K1H 8L6.

E-mail: qyang@ohri.ca

Received 17 February 2005; revised 18 July 2005; accepted 24 August 2005; published online

24 November 2005

Methods

We carried out a population-based retrospective cohort study of all

twin births in the US for the period of 1995–1997, using the

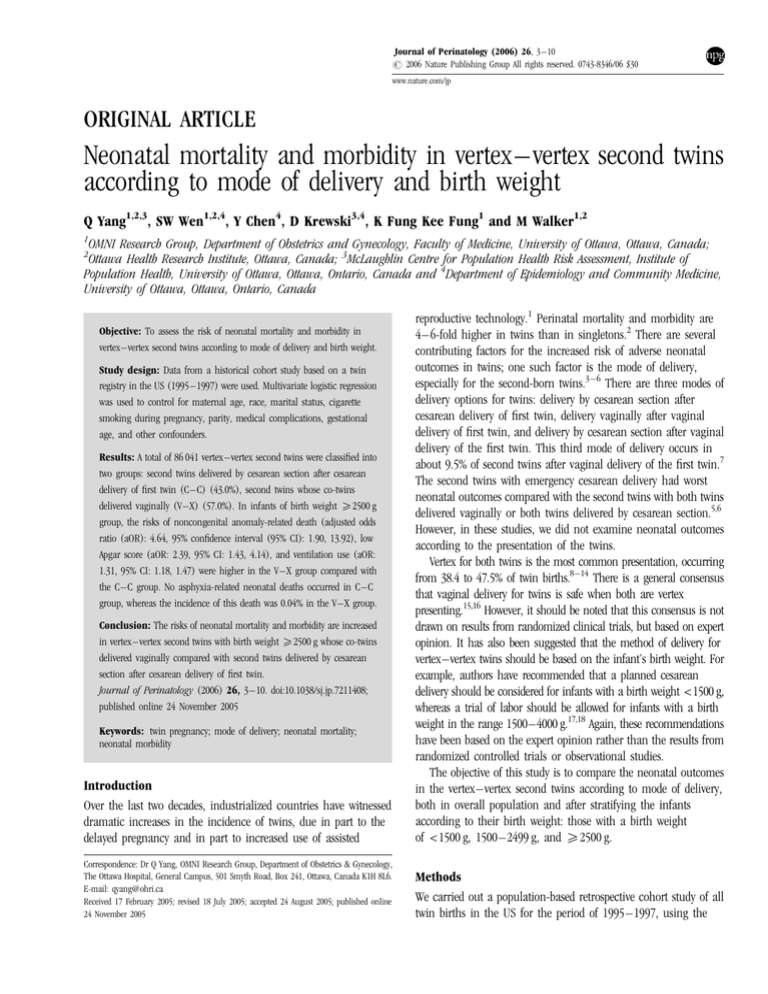

Objective: To assess the risk of neonatal mortality and morbidity in

vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery and birth weight.

Study design: Data from a historical cohort study based on a twin

registry in the US (1995–1997) were used. Multivariate logistic regression

was used to control for maternal age, race, marital status, cigarette

smoking during pregnancy, parity, medical complications, gestational

age, and other confounders.

Results: A total of 86 041 vertex–vertex second twins were classified into

two groups: second twins delivered by cesarean section after cesarean

delivery of first twin (C–C) (43.0%), second twins whose co-twins

delivered vaginally (V–X) (57.0%). In infants of birth weight X2500 g

group, the risks of noncongenital anomaly-related death (adjusted odds

ratio (aOR): 4.64, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.90, 13.92), low

Apgar score (aOR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.43, 4.14), and ventilation use (aOR:

1.31, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.47) were higher in the V–X group compared with

the C–C group. No asphyxia-related neonatal deaths occurred in C–C

group, whereas the incidence of this death was 0.04% in the V–X group.

Conclusion: The risks of neonatal mortality and morbidity are increased

in vertex–vertex second twins with birth weight X2500 g whose co-twins

delivered vaginally compared with second twins delivered by cesarean

section after cesarean delivery of first twin.

Journal of Perinatology (2006) 26, 3–10. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211408;

published online 24 November 2005

Keywords: twin pregnancy; mode of delivery; neonatal mortality;

neonatal morbidity

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

4

Matched Multiple Birth File created by the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention.19 The matching was successful for 98.8%

of twin birth sets.19 Only live births were included in this study.

Live births with gestational age less than 24 weeks or with birth

weight less than 500 g were excluded because these newborn’s

viability can be questionable.

We restricted our study to vertex–vertex second twins. The study

subjects were divided into two groups by mode of delivery: delivery

by cesarean section after cesarean delivery of first twin (C-C),

and all second twins after vaginal delivery of first twin (V–X).

We further divided second group into two subgroups: vaginal

delivery (V–V) and cesarean delivery (V–C). We derived a new

variable, which was birth-weight discordance within the pair of

twins (second twin 25% smaller or 25% larger than the first

twin).

Main study outcomes of interest included neonatal mortality

and morbidity. Neonatal death was defined as live born infant

who died within 28 days of life. To test the hypothesis that the

association between mode of delivery and neonatal mortality would

be stronger in those deaths not caused by lethal congenital

anomaly and those caused by asphyxia, we compared the rates of

noncongenital anomaly-related and asphyxia-related neonatal

mortality among these groups. For noncongenital anomaly-related

neonatal mortality, we excluded deaths with cause of death being

congenital anomaly. The grouping for noncongenital anomaly- or

asphyxia-related neonatal deaths were according to the

International Collaborative Effort on Infant Mortality,20 and the

standard National Center for Health Statistics categories. Neonatal

morbidity examined in this study included lower 5-min Apgar score

(p3), the need for mechanical ventilation, and the occurrence of

seizure.

We first compared the distribution of maternal and infant

characteristics of the three study groups. We then estimated the

crude odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for mode

of delivery using unconditional logistic regression with C-C group

as the reference. Potential confounding variables included

maternal age (<20, 20–29, 30–34, and X35 years), race (white,

not white), marital status (yes, no), cigarette smoking during

pregnancy (yes, no, not stated), parity (0, 1 þ ), one of these

complications (diabetes, pregnancy-associated hypertension,

eclampsia, abruption placenta, and placenta previa) (yes, no), one

of abnormal conditions during labor (precipitous labor, prolonged

labor, dysfunctional labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, cord

prolapse, and fetal distress) (yes, no), birth-weight discordance

(second twin 25% larger, second twin 25% smaller, remaining),

fetal gender (female, male), and gestational age (24–27 weeks,

28–31 weeks, and X32 weeks in the birth weight <1500 g group,

24–35 weeks and X36 weeks both in birth weight 1500–2499,

and X2500 g groups). All analyses were performed using SAS-PC

statistical software version 8 (SAS Inc., NC).

Results

There were 95 977 vertex–vertex second twins in the database. We

excluded 9936 second twins (fetal death (1479), gestational age

<24 completed weeks (1381), birth weight <500 g (283), and

missing information on delivery (6793)), leaving 86 041 eligible

vertex–vertex second twins for analysis. Among them, 36 977

(43.0%) were in the C–C group, 46 071 (53.5%) in the V–V group,

and 2993 (3.5%) in the V–C group. The rate of emergency

cesarean delivery for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the

first twin was 6.1% in all vertex–vertex second twins, 11.3% in

birth weight <1500 g, 5.8% in birth weight 1500–2499 g, and 5.7%

in birth weight X2500 g.

Table 1 displays the distribution of maternal and infant

characteristics among the three study groups. The proportions of

non-white race, unmarried, high parity, and late prenatal care

initiation were higher in the V–C group than the C–C group

(Table 1). The differences in maternal and fetal characteristics

between the V–V group and the C–C group tended to be smaller.

Table 1 Maternal and fetal characteristics for the vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery, US, 1995–1997

Characteristics

C–C group

Number

V–V group

V–C group

Percent

Number

Percent

Number

Percent

Maternal age (years)

<20

20–29

30–34

X35

2463

16 185

11 024

7305

6.7

43.8

29.8

19.7

3658

22 235

13 003

7175

7.9

48.3

28.2

15.6

230

1448

825

490

7.7

48.4

27.5

16.4

Maternal race

White

Non-white

29 220

7757

79.0

21.0

36 839

9232

80.0

20.0

2143

850

71.6

27.4

Journal of Perinatology

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

5

Table 1 Continued

Characteristics

C–C group

Number

V–V group

V–C group

Percent

Number

Percent

Number

Percent

Marital status

Married

Others

27 431

9546

74.2

25.8

33 353

12 718

72.4

27.6

1990

1003

66.5

33.5

Education

<12 years

12 years

13–15 years

X16 years

5624

11 389

8700

10 891

15.4

31.1

23.8

29.7

7211

14 253

10 586

13 499

15.8

31.3

23.2

29.7

544

954

657

809

18.3

32.2

22.2

27.3

Smokinga

No

Yes

Unavailable

2958

25 222

8797

8.0

68.2

23.8

4083

32 926

9062

8.9

71.4

19.7

308

2101

584

10.3

70.2

19.5

Parity

0

1+

16 496

20 462

44.6

55.4

18 105

27 936

39.3

60.7

1043

1949

34.9

65.1

Prenatal care initiation

First trimester

Second trimester

Third trimester or None

31 409

3862

747

87.2

10.7

2.1

38 691

5048

1197

86.1

11.3

2.6

2453

350

117

84.0

12.0

4.0

Maternal complication

No

Yes

31 320

5657

84.7

15.3

41 673

4398

90.4

9.6

2620

373

7.5

12.5

Infant gender

Male

Female

18 506

18 471

50.1

49.9

23 030

23 041

50.0

50.0

1316

1677

44.0

56.0

Gestational age (weeks)

24–31

32–35

36–44

4.54

10 292

22 175

11.1

28.2

60.7

3231

12 386

29 897

7.1

27.2

65.7

360

833

1769

12.2

28.1

59.7

Birth weight >4000 g

No

Yes

36 904

73

99.8

0.2

46 009

62

99.9

0.1

2987

6

99.8

0.2

Birth weight discordance

Second twin 25% larger

Second twin 25% smaller

Remaining

2505

2645

31 827

6.8

7.1

86.1

2759

1773

41 539

6.0

3.8

90.2

228

108

2657

7.6

3.6

88.8

a

The State of California, Indiana, South Dakota, and New York (except for New York city) did not send data on smoking. C–C group: delivery by cesarean section after cesarean delivery

of first twin; V–V group: delivery vaginally after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–C group: the second twins delivered by cesarean section after vaginal delivery of the first twin.

Journal of Perinatology

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

6

The proportion of maternal complications was significantly higher in the

C–C group as compared with both V–V and V–C groups (Table 1).

In second twins with birth weight <1500 g, the incidence of

noncongenital anomaly-related death was significantly higher in

the V–X group (8.29%) than in the C–C group (5.81%). The aOR

was 1.24 (1.01, 1.52). However, the relationship was only true in

the V–V group when the V–X group was broken into the V–V

group and the V–C group. The incidence of low Apgar score was

significantly higher in the V–X group (3.94%) than in the C–C

group (2.42%). The OR and its 95% CI was 1.66 (1.26, 2.17). After

adjusting for confounders, the aOR was 1.38 (1.04, 1.84). Again,

the relationship was true only in the V–V group, and not in the

V–C group (Table 2).

In second twins with birth weight 1500–2499 g, the ORs and its

95% CI were 2.97 (1.27, 6.12) for noncongenital anomaly-related

death, 7.36 (1.51, 30.01) for asphyxia-related death, 3.47 (1.92,

5.90) for low Apgar score, 1.84 (1.54, 2.18) for ventilation use, and

7.37 (2.50, 19.88) for occurrence of seizure in the V–C group

compared with the C–C group. The aORs were slightly attenuated

by adjusting for confounders. However, these relationships were

not true in the V–X group when we combined the V–V group and

V–C group (Table 3).

In second twins with birth weight X2500 g, the ORs and its

95% CI were 4.28 (1.81, 12.56) for noncongenital anomaly-related

death, 2.00 (1.22, 3.41) for low Apgar score, 1.22 (1.10, 1.36) for

ventilation use in the V–X group compared with the C–C group.

Adjustment for potential confounding factors did not change these

results. Moreover, these relationships were also true in both the

V–V group and the V–C group and the ORs were much higher in

the V–C group. No asphyxia-related death occurred in the C–C

Table 2 Comparison of neonatal outcomes in vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery (birth weight 500–1499 g), US, 1995–1997

Type of neonatal outcomes and mode of delivery

Noncongenital anomaly-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Number (%) of outcomes

Crude OR (95% CI)

Adjusted OR (95% CI)a

235

243

224

19

(5.81)

(8.29)

(8.62)

(5.71)

Reference

1.47 (1.22, 1.77)

1.53 (1.27, 1.85)

0.98 (0.59, 1.55)

Reference

1.24 (1.01, 1.52)

1.32 (1.07, 1.62)

0.71 (0.40, 1.19)

10

13

12

1

(0.24)

(0.43)

(0.45)

(0.29)

Reference

1.80 (0.79, 4.22)

1.87 (0.81, 4.44)

1.22 (0.07, 6.41)

Reference

1.49 (0.63, 3.66)

1.57 (0.65, 3.92)

0.89 (0.05, 5.00)

Low Apgar score (p3 at 5 minutes)

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

100

118

103

15

(2.42)

(3.94)

(3.88)

(4.42)

Reference

1.66 (1.26, 2.17)

1.63 (1.23, 2.15)

1.87 (1.03, 3.16)

Reference

1.38 (1.04, 1.84)

1.41 (1.05, 1.89)

1.23 (0.64, 2.17)

Ventilation use

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

975

701

619

82

(23.56)

(23.39)

(23.29)

(24.19)

Reference

0.99 (0.89, 1.11)

0.99 (0.88, 1.11)

1.04 (0.80, 1.34)

Reference

0.99 (0.88, 1.12)

1.00 (0.88, 1.13)

0.91 (0.68, 1.19)

(0.17)

(0.13)

(0.15)

(0.00)

Reference

0.79 (0.21, 2.61)

0.89 (0.23, 2.95)

N/A

Reference

0.67 (0.17, 2.31)

0.80 (0.20, 2.77)

N/A

Asphyxia-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Occurrence of seizure

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

a

7

4

4

0

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) were adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, parity, medical complications (diabetes, pregnancyassociated hypertension, and abnormal labor), abnormality during delivery (precipitous labor, prolonged labor, dysfunctional labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, cord prolapse, and fetal

distress), fetal gender, and gestational age (24–27 weeks, 28–31 weeks, and X32 weeks). C–C group: delivery by cesarean section after cesarean delivery of first twin; V–X group: all

second twins after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–V group: delivered vaginally after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–C group: the second twins delivered by cesarean section after

vaginal delivery of the first twin. N/A: not applicable.

Journal of Perinatology

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

7

Table 3 Comparison of neonatal outcomes in vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery (birth weight 1500–2499 g), US, 1995–1997

Type of neonatal outcomes and mode of delivery

Noncongenital anomaly-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Asphyxia-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Low Apgar score (p3 at 5 min)

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Ventilation use

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Occurrence of seizure

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Number (%) of outcomes

Crude OR (95% CI)

Adjusted OR (95% CI)a

33

34

26

8

(0.21)

(0.15)

(0.12)

(0.61)

Reference

0.73 (0.45, 1.19)

0.60 (0.35, 0.99)

2.97 (1.27, 6.12)

Reference

0.75 (0.45, 1.26)

0.64 (0.37, 1.09)

1.92 (0.75, 4.28)

5

6

3

3

(0.03)

(0.03)

(0.01)

(0.23)

Reference

0.86 (0.26, 2.97)

0.45 (0.09, 1.85)

7.36 (1.51, 30.01)

Reference

1.06 (0.31, 3.81)

0.56 (0.11, 2.36)

5.42 (1.02, 21.66)

57

88

72

16

(0.36)

(0.39)

(0.34)

(1.22)

Reference

1.10 (0.79, 1.54)

0.96 (0.68, 1.36)

3.47 (1.92, 5.90)

Reference

1.13 (0.80, 1.59)

0.99 (0.69, 1.42)

2.36 (1.29, 4.12)

(7.41)

(7.85)

(7.55)

(12.82)

Reference

1.07 (0.99, 1.15)

1.02 (0.94, 1.10)

1.84 (1.54, 2.18)

Reference

1.11 (1.02, 1.20)

1.06 (0.98, 1.16)

1.75 (1.46, 2.09)

(0.06)

(0.08)

(0.05)

(0.46)

Reference

1.21 (0.56, 2.75)

0.83 (0.35, 2.00)

7.37 (2.50, 19.88)

Reference

1.47 (0.66, 3.50)

0.99 (0.40, 2.52)

5.28 (1.69, 15.47)

1188

1767

1599

168

10

17

11

6

a

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) were adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, parity, medical complications (diabetes, pregnancyassociated hypertension, and abnormal labor), abnormality during delivery (precipitous labor, prolonged labor, dysfunctional labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, cord prolapse, and fetal

distress), fetal gender and gestational age (24–35 weeks and X36 weeks). C–C group: delivery by cesarean section after cesarean delivery of first twin; V–X group: all second twins

after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–V group: delivered vaginally after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–C group: the second twins delivered by cesarean section after vaginal delivery

of the first twin.

group, whereas the incidence of this death was 0.45% in the V–C

group (Table 4).

Discussion

Our large population-based study found a 6.1% rate of emergency

cesarean delivery for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the

first twin in vertex–vertex twin pairs, lower than 9.5% in all second

twins7 and much lower than 24.8% in vertex–nonvertex second

twins of the same population.21 This finding is consistent with

physicians’ consensus that vaginal delivery for twins is safer when

both twins are vertex than vertex–nonvertex presentation.15,16 Only

one previous study has examined the mode of delivery for secondborn twin with vertex–vertex presentation.22 The rate of cesarean

delivery for the second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin in

that study was 16.9%,22 which was much higher than the rate

observed in our study (6.1%). The study by Sullivan et al.22 was

based on a single obstetric care center with a very small sample

(106 twin sets). The rates of emergency cesarean delivery for the

second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin were 11.3% in

birth weight <1500 g, 5.8% in birth weight 1500–2499 g, and 5.7%

in birth weight X2500 g in our study, which indicate that

physicians may have a lower threshold to perform an emergency

cesarean section for the second-born twin when the fetus was likely

to be <1500 g. As a result, the rate of cesarean delivery for the

second twin after vaginal delivery of the first twin was higher in

this group of infants than those with a birth weight X1500 g.

Our study found that in second twins with birth weight

<1500 g, the risks of noncongenital anomaly-related neonatal

death, and low Apgar score were increased in all second twins after

Journal of Perinatology

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

8

Table 4 Comparison of neonatal outcomes in vertex–vertex second twins according to mode of delivery (birth weight X2500 g), US, 1995–1997

Type of neonatal outcomes and mode of delivery

Number (%) of outcomes

Crude OR (95% CI)

Adjusted OR (95% CI)a

Noncongenital anomaly-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

5

30

18

12

(0.03)

(0.13)

(0.08)

(0.90)

Reference

4.28 (1.81, 12.56)

2.72 (1.09, 8.24)

30.29 (11.22, 95.31)

Reference

4.64 (1.90, 13.92)

2.69 (1.02, 8.39)

19.98 (6.82, 66.58)

Asphyxia-related deaths

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

0

10

4

6

(0.00)

(0.04)

(0.02)

(0.45)

Reference

N/A

N/A

N/A

Reference

N/A

N/A

N/A

Low Apgar score (p3 at 5 min)

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

20

56

40

16

(0.12)

(0.24)

(0.18)

(1.20)

Reference

2.00 (1.22, 3.41)

1.51 (0.90, 2.64)

10.13 (5.16, 19.55)

Reference

2.39 (1.43, 4.14)

1.84 (1.07, 3.27)

5.86 (2.90, 11.68)

594

1010

896

114

(3.56)

(4.31)

(4.06)

(8.55)

Reference

1.22 (1.10, 1.36)

1.15 (1.03, 1.28)

2.54 (2.05, 3.11)

Reference

1.31 (1.18, 1.47)

1.24 (1.11, 1.40)

2.08 (1.66, 2.60)

9

18

12

6

(0.05)

(0.08)

(0.05)

(0.45)

Reference

1.43 (0.66, 3.33)

1.01 (0.43, 2.47)

8.38 (2.81, 23.28)

Reference

1.46 (0.66, 3.46)

1.01 (0.42, 2.50)

6.35 (2.01, 18.75)

Ventilation use

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

Occurrence of seizure

C–C group

V–X group

V–V group

V–C group

a

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) were adjusted for maternal age, race, marital status, cigarette smoking during pregnancy, parity, medical complications (diabetes, pregnancyassociated hypertension, and abnormal labor), abnormality during delivery (precipitous labor, prolonged labor, dysfunctional labor, cephalopelvic disproportion, cord prolapse, and fetal

distress), fetal gender, and gestational age (24–35 weeks and X36 weeks). C–C group: delivery by cesarean section after cesarean delivery of first twin; V–X group: all second twins

after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–V group: delivered vaginally after vaginal delivery of first twin; V–C group: the second twins delivered by cesarean section after vaginal delivery of

the first twin. N/A: not applicable.

vaginal delivery of first twin as compared with those with both

twins delivered by cesarean section. However, none of the ORs was

larger than 2. Immediate action by physicians might have

prevented some deaths or other severe conditions from occurring

in these infants, and the V–C-related neonatal mortality and

morbidity was therefore less frequent in them because physicians

might have a lower threshold to perform an emergency cesarean

section for the second-born twin when the fetus was likely to be

<1500 g. However, we should interpret our results with caution

because this conclusion was not drawn from randomized clinical

trial, and for those delivered by cesarean section, both selective and

emergency cesarean section were included. These cases might have

different conditions. When there is an indication such as placenta

previa or severe pre-eclampsia, elective cesarean section is likely to

be offered for the delivery of both twins. As a result, the effect of

Journal of Perinatology

mode of delivery on neonatal mortality may be biased towards a

higher risk of neonatal mortality in the group with both twins

delivered by cesarean section.

In second twins with birth weight 1500–2499 g, none of the

risks of mortality and morbidity was higher than in all second

twins after vaginal delivery of first twin as compared with those

both twins delivered by cesarean section, which suggests that

routing cesarean section for vertex–vertex second twins may not be

necessary. Again, we should interpret our results with caution

because this conclusion was not from randomized clinical trial.

However, we should pay attention to the higher risks of mortality

and morbidity in those delivered by cesarean section after vaginal

delivery of the first twin. Physicians may be more reluctant to

perform emergency cesarean section for the second twin when the

fetus was likely to be X1500 g. As a result, delay in intervention

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

9

by physicians might have caused some deaths or other severe

conditions in these infants, and the V–C-related neonatal mortality

and morbidity were therefore much higher.

In second twins with birth weight X2500 g, the risks of

mortality and morbidity were significantly higher in all second

twins who delivered after vaginal delivery of first twin. And these

ORs were much higher in those cesarean delivered after vaginal

delivery of first twin. Again, physicians might be more reluctant to

perform emergency cesarean section for the second twin when the

fetus was likely to be X2500 g. We suggest that routine cesarean

section might be beneficial for those with birth weight X2500 g.

However, our conclusion needs to be confirmed from randomized

clinical trial.

The limitations of our data should be pointed out. Our study

used birth certificate data, which might underestimate certain

complications of pregnancy.23 Other qualities of the data, such as

fetal presentation, order of the birth, and the causes of neonatal

death might be uncertain. As this was a cohort study, there might

be some pre-existing reasons for why a physician chose to offer a

patient with vertex–vertex twins a trial of labor, as opposed to an

outright cesarean section. The reasons for the decision to perform a

cesarean section or vaginal delivery were not available in the data.

Selection bias seemed to be the major methodological issue of this

study. There might also be characteristics of patients who agreed to

a trial of labor that were different from those who desired an

elective cesarean section for both twins. Obviously, the only way to

obtain the most unbiased estimate of the effects of mode of delivery

would be to do a prospective, randomized control trial. In addition,

some of the relative risks were based on very small number of

subjects. Endogeneity is the second major methodological issue.

Endogeneity refers to the fact that an independent variable

included in the model is potentially a choice variable, correlated

with unobservables relegated to the error term. The use of

unconditional logistic regression in this study could not adequately

address endogeneity.24 Potential errors in the coding of cause of

death may not be random. For example, for unknown reasons, the

incidence of asphyxia-related death in this data was lower than

that found in other studies.25 Another limitation is that we did not

analyze separately the twins delivered by the university

perinatologist and residents from the twins delivered by the private

obstetricians because we have no information on that. However,

Greig et al.26 found that there was no significant difference in the

percentage of twins delivered by cesarean section (48 vs 49%)

between the two groups.

In conclusion, our large population-based study found the

emergency cesarean delivery rate in vertex–vertex second twins

whose co-twins delivered vaginally was 6.1%. The risks of mortality

and morbidity are significantly increased in second twins with birth

weight X2500 g whose co-twins delivered vaginally compared with

second twins delivered by cesarean section after cesarean delivery of

first twin.

References

1 Blondel B, Kaminski M. Trends in the occurrence, determinants, and

consequences of multiple births. Semin Perinatol 2002; 26: 239–249.

2 Power WP, Wampler NS. Further defining the risks confronting twins.

Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 175: 1522–1528.

3 Rydhstroem H. Should all twins be delivered by caesarean section?

A preliminary report. Twin Res 2001; 4: 156–158.

4 Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Birth order, gestational age, and risk of

delivery related perinatal death in twins: retrospective cohort study. BMJ

2002; 325: 1004–1009.

5 Wen SW, Fung Kee Fung K, Oppenheimer L, Demissie K, Yang Q, Walker M.

Neonatal mortality in second twin according to cause of death, gestational

age, and mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynocol 2004; 191: 778–783.

6 Wen SW, Fung Kee Fung K, Oppenheimer L, Demissie K, Yang Q, Walker M.

Neonatal morbidity in second twin according to gestational age at birth and

mode of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynocol 2004; 191: 773–777.

7 Wen SW, Fung Kee Fung K, Oppenheimer L, Demissie K, Yang Q, Walker M.

Occurrence and clinical predictors of emergent cesarean delivery for second

twin. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103: 413–419.

8 Chervenak FA, Johnson RE, Berkowitz RL, Hobbins JC. Intrapartum external

version of the second twin. Obstet Gynecol 1983; 62: 160–165.

9 Crawford JS. A prospective study of 200 consecutive twin deliveries.

Anaesthesia 1987; 42: 33–43.

10 Divon MY, Marin MJ, Pollack RN, Katz NT, Henderson C, Aboulafia Y et al.

Twin gestation: fetal presentation as a function of gestational age. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168: 1500–1502.

11 Kelsick F, Minkoff H. Management of the breech second twin. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1982; 144: 783–786.

12 Thompson SA, Lyons TJ, Makowski EL. Outcomes of twin gestation at the

University of Colorado Health Science centre. J Reproduct Med 1987; 32:

328–329.

13 Laros RK, Dattel BJ. Management of twin pregnancy; the vaginal route is still

safe. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 158: 1330–1338.

14 Piekarski P, Czajkowski K, Maj K, Milewczyk P. Neonatal outcome depending

on the mode of delivery and fetal presentation in twin gestation (abstract).

Ginekol Pol 1997; 68: 187–192.

15 Boggess KA, Chisholm CA. Delivery of the nonvertex second twin: a review of

the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1997; 52: 728–735.

16 Blickstein I. Cesarean section for all twins? J Perinat Med 2000; 28:

169–174.

17 Anonymous. Special problems of multiple gestations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet

1999; 64: 323–333.

18 Barrett J, Bocking A. The SOGC consensus statement on management of twin

pregnancies (Part I). J SOGC 2000; 91: 519–532.

19 National Center for Health Statistics. 1995–1997 Matched Multiple Birth

Data Set. NCHS CD-ROM Series 21, No. 12. U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Hyattsville,

Maryland; 2000.

20 Cole S, Hartford RB, Bersjo P, McCarthy B. International collaborative effort

(ICE) in birth weight, plurality, perinatal and infant mortality. Acta Obstet

Gynecol Scand 1989; 68: 113–117.

21 Yang Q, Wen SW, Chen Y, Krewski D, Fung Kee Fung K, Walker M. Neonatal

mortality and morbidity in vertex–nonvertex second twins according to mode

of delivery and birth weight. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 840–847.

Journal of Perinatology

Neonatal mortality and morbidity in vertex–vertex second twins

Q Yang et al

10

22

23

24

Sullivan CA, Harkins D, Seago DP, Roberts WE, Morrison JC. Cesarean

delivery for the second twin in the vertex–vertex presentation: operative

indications and predictability. South Med J 1998; 91: 155–158.

Huston P, Naylor CD. Health services research: reporting on studies using

secondary data sources. Can Med Assoc J 1996; 155: 1697–1702.

Millimet D. What is the difference between ‘endogeneity’ and ‘sample

selection bias’? Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) for STATA, http://

www.stata.com/support/faqs/stat/bias.html.

Journal of Perinatology

25

26

Wen SW, Joseph KS, Kramer MS, Demissie K, Oppenheimer L, Liston R,

et al., For the Fetal and Infant Mortality Study Group. Canadian

Perinatal Surveillance System. Recent secular trends in fetal and

infant outcomes among post-term pregnancies. Chron Dis Can 2001; 22:

1–5.

Greig P, Veille J, Morgan T, Henderson L. The effect of presentation and

mode of delivery on neonatal outcome in the second twin. Am J Obstet

Gynecol 1992; 167: 901–906.