Decolonization Case Study: Egypt World History, Culture, and Geography

advertisement

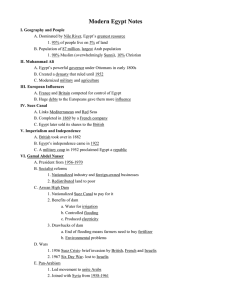

Decolonization Case Study: Egypt World History, Culture, and Geography Egypt was conquered by Arabs in 642 during their expansion and established firm control of the area. From 1250 to 1517, Egypt was ruled by a military caste called the Mamluks. However, the Mamluks were conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1517. Egypt remained a Turkish territory for four centuries. In 1805 an Albanian soldier, Muhammad, was appointed ruler of Egypt. He succeeded in establishing his own dynasty that ruled the country, first under nominal Ottoman control, and later as a British protectorate. Muhammad Ali and the dynasty that he began, the Khedives, destroyed feudalism, stabilized the country, encouraged the planting of cotton, and opened the land to European penetration and development. In 1859 work began on a ship canal to connect the Mediterranean Sea with the Red Sea. The canal, known as the Suez Canal, begun under the direction of the French promoter Ferdinand de Lesseps, took ten years to complete. After the completion of the Suez Canal (1869), Egypt became a world transportation hub, and therefore, a desirable strategic location. However, financial mismanagement of the building of the canal led to bankruptcy. These developments led to rapid expansion of British and French financial oversight. That, in turn, provoked popular resentment, unrest, and finally, revolt among the Egyptians in 1879. British forces crushed the revolt in 1882, and England seized control of Egypt's government in 1882. To secure its interests in World War I (1914-18), Britain declared a formal protectorate over Egypt on 18 December 1914. After the war and open revolt, England recognized Egypt as an officially sovereign country and handed rule back over to the Khedives in 1922. Arab nationalism in Egypt gathered momentum in World War II (1939-45) under the leadership of groups like the Muslim Brotherhood and Free Officers. Amidst many political and social problems, the Free Officers engineered a successful coup in 1952, and Gamal Abdul Nasser, leader of the revolution, came to power. To increase the production in his country, Nasser entered into preliminary agreements with the United States, Britain, and the United Nations to finance a new dam at Aswân. At the same time, he negotiated economic aid and arms shipments from the Soviet Union and its allies in Eastern Europe. This agreement angered the United States. In response, the United States withheld its financial backing for the dam. In retaliation, on 26 July 1956, President Nasser took control of the Suez Canal and announced that he would use the profits from its operations to build the dam. The dam was completed with aid and technical assistance from the Soviet Union. In 1967, as political opponents gained strength, Nassar declared Emergency Law. Under the law, police powers were extended, constitutional rights suspended and censorship was legalized. The law sharply circumscribed any non-governmental political activity: street demonstrations, non-approved political organizations, and unregistered financial donations were banned. Some 17,000 people were detained under the law, and estimates of political prisoners ran as high as 30,000. Under the "state of emergency", the government had the right to imprison individuals for any length of time without trial. The government claimed that opposition groups like the Muslim Brotherhood could come into power in Egypt if parliamentary elections occurred. When Nasser died on 28 September 1970, his vice president, Anwar al-Sadat, became president. President Sadat firmly established his hold on the government and began to implement pragmatic economic and social policies. These included improved relations with the United States. Additionally, due to his frustration over territorial losses to Israel, President Sadat eventually made the bold move of entering into negotiations with Israel, mediated by United States President Jimmy Carter, at Camp David, Maryland. Following further negotiations, Sadat signed the Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty in Washington, D.C., on 26 March 1979. For their roles as peacemakers, Sadat and the Israeli prime minister were jointly awarded the 1978 Nobel Peace Prize. But other Arab leaders denounced the accords and sought to isolate Egypt within the Arab world for its treaty with Israel. In early October 1981, Sadat was assassinated in Cairo by four Muslim fundamentalists. The vice president, Hosni Mubarak, who had been Sadat's closest adviser, succeeded him as president. Mubarak pledged to continue Sadat's course of action, implementing policies of moderation and peacemaking abroad and gradual political liberalization and movement towards the free market at home. Mubarak was reelected president in 1987, 1993, 1999, and 2005. The most serious opposition to the Mubarak government is from outside the political system. Religious parties are banned and, as a consequence, Islamic militants have resorted to violence against the regime. Security forces have cracked down hard, but the militant movement has gathered strength, fueled by discontent with poor economic conditions, corruption, secularism, and Egypt's ties with the United States and Israel. In 1999, Mubarak survived an assassination attempt just before he was reelected to a fourth term. In the face of protests, in 2005, Egypt changed its constitution to allow opposition candidates to run for president. However, religious parties remained banned and potential candidates were subject to strict requirements. The presidential election held on 7 September 2005 saw President Mubarak win a fifth term in office. Although the election was marked by voting irregularities and voter intimidation, opposition candidates were allowed to campaign freely and were given equal time on television. Yet, the law dictated by the state of emergency first declared in 1967 remained in place until the Arab Spring movement of 2011.