The Record, Hackensack, N.J., personal finance column 309&VName=PQD

advertisement

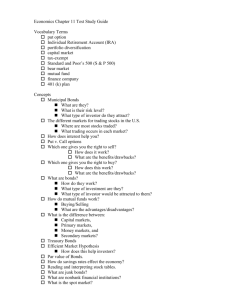

The Record, Hackensack, N.J., personal finance column Kathleen Lynn. Knight Ridder Tribune Business News. Washington: May 4, 2005. pg. 1 http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb?did=832495581&sid=3&Fmt=3&clientId=68814&RQT= 309&VName=PQD Abstract (Document Summary) As a result, they're becoming more popular. Assets in life-cycle and target-retirement funds have risen to $139.7 billion in 2004, up from $57.9 billion in 1999, according to Lipper, which tracks mutual fund performance. And more than half of large employers now include target-retirement plans in their 401(k)s, simplifying the process for workers who often feel overwhelmed and confused by too many investment choices. The funds, which are offered by many investment companies, come in two varieties. The first is the life-cycle or life-strategy fund, which offers a mix of stocks and bonds tailored to the needs of different investors. For example, Vanguard's LifeStrategy Growth Fund is 90 percent stocks and 10 percent bonds, and its LifeStrategy Income Fund is 30 percent stocks and the rest is bonds and cash. Consider: If you put $3,000 a year into a target-retirement fund or life-strategy fund and earned an average of 5 percent, after 30 years, you'd have $194,417 in the Vanguard fund, versus $137,855 in a similar American Express fund. Full Text (613 words) Copyright 2005, The Record, Hackensack, N.J. Distributed by KnightRidder/Tribune Business News. For information on republishing thiscontent, contact us at (800) 6612511 (U.S.), (213) 237-4914(worldwide), fax (213) 237-6515, or e-mail reprints@krtinfo.com. To see more of The Record, or to subscribe to the newspaper, go to http://www.NorthJersey.com. Copyright May 4--Investing seems complicated, but it doesn't have to be. In fact, it shouldn't be. Case in point: target-retirement or life-cycle mutual funds. These are one-decision funds, offering a mix of investments that can carry an investor through years -- or even decades. As a result, they're becoming more popular. Assets in life-cycle and target-retirement funds have risen to $139.7 billion in 2004, up from $57.9 billion in 1999, according to Lipper, which tracks mutual fund performance. And more than half of large employers now include target-retirement plans in their 401(k)s, simplifying the process for workers who often feel overwhelmed and confused by too many investment choices. The funds, which are offered by many investment companies, come in two varieties. The first is the life-cycle or life-strategy fund, which offers a mix of stocks and bonds tailored to the needs of different investors. For example, Vanguard's LifeStrategy Growth Fund is 90 percent stocks and 10 percent bonds, and its LifeStrategy Income Fund is 30 percent stocks and the rest is bonds and cash. Investors can pick one of these funds, based on their risk tolerance, and put in all their money, confident they've got their bases covered. But as people age, their financial needs change. That's why the target-retirement funds are an even better choice for many investors. Like the life-cycle funds, they offer a mix of stocks and bonds -- but the blend changes as the investor ages. Generally, young investors with decades till retirement are better off with a hefty serving of stocks in their portfolios, because stocks grow more over time. But older workers, close to retirement, are more concerned about protecting their assets from the volatility of stocks. So Vanguard's Target Retirement 2045 is 90 percent stocks, but the 2005 fund is 35 percent stocks. To find the best for you, just pick the date closest to when you hope to retire. (You can also use these for other purposes, such as a child's college education that starts around 2015, for example.) There are variations among these funds. Some fund families are more aggressive in the mix of stocks versus bonds for the various retirement dates. But the most important difference is their cost. These are basically funds that hold other mutual funds, so you pay the annual expenses of the underlying investments. Also, some -- but not all -- of the funds add an additional layer of fees. Fidelity, for example, adds 0.08 percent on top of the costs of the underlying funds, and Vanguard and T. Rowe Price add no extra fee. I think those extra fees are overkill. Imagine buying milk, oranges, cereal and ice cream at Pathmark. We all understand the supermarket has to make a profit on each item. But what if the cashier tried to charge an additional fee just for putting the different foods into one grocery bag? Most of us wouldn't stand for that. I don't think we should stand for it from investment companies, either. Annual expense ratios range from Vanguard's rock-bottom costs, of about 0.25 percent, to above 2 percent for American Express, among others. That may not sound like a big deal, but because these are long-term investments, the costs compound alarmingly over time. Consider: If you put $3,000 a year into a target-retirement fund or life-strategy fund and earned an average of 5 percent, after 30 years, you'd have $194,417 in the Vanguard fund, versus $137,855 in a similar American Express fund. Which nest egg would you rather own when you retire and move to Florida? Credit: The Record, Hackensack, N.J.