Teacher Work Sample Manual for Mentors: The Renaissance Partnership For Improving Teacher Quality

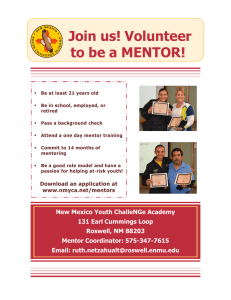

advertisement