Mesopotamia Political Ancient: Comparison of River Valley

advertisement

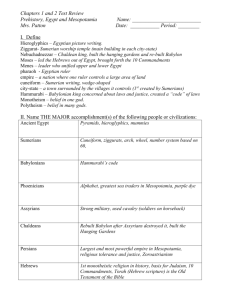

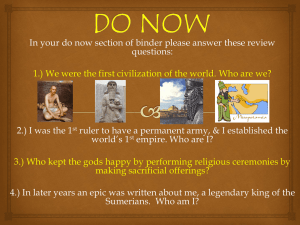

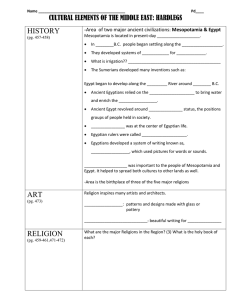

Ancient: Comparison of River Valley Civilizations NAME: ___________________________ Mesopotamia Political Geographic location left Mesopotamia vulnerable to outside invasion. Organized around independent city-states each with its own king, although there was a united empire for a time under the Babylonians. Kings were powerful, but not divine Gov’t leaders promoted public works projects (dams, irrigation, temples) that benefited the whole community Military forces, administrators and tax collectors ensured order/delivered food Leaders oversaw the construction of defensive walls and recruited/trained large military forces Nearly constant competition between city-states and outside invasion led to formation of formal government institutions, ethnic diversity & unity, and pessimistic worldview Later groups (Babylonians) standardized legal procedures, set up courts and handed down harsh punishments for lawbreakers (“eye for an eye”) as in Hammurabi’s Code Used writing system to record policies, populations, and business transactions Government collected barley as tax and taxed labor (a labor draft known as a corvee tax) Economic Most workers were farmers whose agriculture depended on unpredictable flooding of Tigris and Euphrates rivers As governments formed large scale irrigation projects (canals, dams) were put into place built by workers drafted by the government. These projects allowed for surplus food production Food surplus allowed for development of first cities, which became centers of population, job specialization, political/military authority, and trade. Large marketplaces are evidence of extensive interregional trade (including Indus and Nile river valleys) and importance of merchants Technologies such as the wheel, sailboats, chariots, bronze, and early iron metallurgy aided the economy (exporting silver, importing timber from Lebanon, importing the semiprecious stone lapis lazuli from the Indus River Valley) Specialized labor systems included farmers, metallurgist, merchants, craftsmen/artisans, political administrators, priests, slaves Social Unpredictable flooding and dependence on nature resulted in pessimistic worldview and polytheistic religion of powerful & often cruel gods Social classes: 1) Government officials & priests 2) free land-owning class 3) dependent farmers and artisans 4) slaves for domestic service (could purchase freedom) Large priest class became members of the elite due to importance of polytheistic religion Scribes became members of elite for their education and rare ability to use written language. In addition to record keeping, great literary works like the Epic of Gilgamesh were created Women lived in a strictly patriarchal system with few rights. Women of upper classes less equal than lower class counterparts, but marriage contracts and veils were common, men could sell their wives & children into slavery to pay off debts, and men were not punished for adultery whereas adulterous women received the death penalty) Sumerians are the most accomplished of the Mesopotamian civilizations (first wheel, first writing system - Cuneiform, first plow, first sailboat, first lunar calendar – advanced astronomy, math based on 60 – 3600 circle) Mesopotamia Some of the world’s earliest civilizations emerged in a region called Mesopotamia, meaning “between the rivers,” in modern day Iraq. By 3500 B.C.E. a number of cities, including Ur and Uruk, emerged sharing a common culture known as Sumerian. These cities, surrounded by protective walls, were more than a mile in diameter and home to more than 30,000 people. Most residents were farmers, living in huts made of sun-baked mud bricks, who tended their crops by day in nearby fields. But other city-dwellers, supported by the farmers' surplus food, specialized in other occupations. Their numbers included artisans, merchants, laborers, priests and priestesses, soldiers, and government officials. Conflict was common among Sumerian cities, many of which were city-states, independent urban political domains that controlled the surrounding countryside. Eager to enhance their power and wealth, larger city-states sometimes sought to swallow up others, provoking periodic wars. Leaders who emerged in combat often became kings and officials. Over time the kings amassed power to command armies, levy tribute and taxes, dispense justice, and organize the building of roads, canals, and dikes. In many places kingship became hereditary, as rulers passed on power to their sons, reflecting the patriarchal structure of Sumerian society and families. Officials helped the kings govern, while priests and priestesses exalted them as descendants of the gods. Royal authority was thus reinforced by religion. The most famous Sumerian ruler was King Gilgamesh, hero of the Epic of Gilgamesh, a magnificent narrative poem from the third millennium B.C.E. In this epic the handsome young king, described as part god and part man. Confronted by gods, Gilgamesh searches for immortality, only to learn that eternal life is beyond his grasp. The epic exhibits fundamental features of Mesopotamian religion. Like many ancient belief systems, it was polytheistic, meaning that people worshiped more than one god. Gods and goddesses personified forces central to agricultural society, such as earth, sun, water, sky, fertility, and storms who were temperamental figures, portrayed in human form and believed to affect every aspect of life. But overall outlook was gloomy: humans had to serve unpredictable and spiteful gods in this life, with little hope for better fate in the next life. Religion nonetheless played a central role in early societies. It supplied an explanation for the forces of nature, and a way for people to try to influence those forces. It provided a focus for festivals, such as new year holidays in spring, celebrating life's natural cycles with rituals, dances, and songs. It exalted rulers as divine agents, enhancing their authority and helping them maintain order. Priests and priestesses, often family members or devoted followers of rulers, heralded the rulers as godlike beings descended from divinities and performed rituals intended to bring divine favor on the realm. To further enhance their status and prestige, rulers built splendid temples to the gods and palaces for themselves. Some Sumerian cities constructed ziggurats, massive brick towers ascending upward in tiers, typically topped by shrines for religious rituals. Dominating urban landscapes, ziggurats also served as symbols of power and as lookout towers for defense. Governance and religion were thus intertwined, each supporting the other. Secured by this support and sustained by surplus food, Sumerians made great strides in other endeavors. They promoted regional commerce, pioneered the use of wheels, fashioned metals into tools and weapons, devised ways to keep track of time, performed architectural and engineering feats, and invented writing. Although Sumer's farms produced abundant wheat and barley, and its sheep supplied ample wool, woods and metals there were scarce. So Sumerians traded with other lands, exchanging their textiles and grains for cedar wood and copper from the eastern Mediterranean, gold from Egypt, and gems from what is now Iran. To carry these goods, Sumerians fashioned wooden boats for rivers, cargo ships for seas, and wheeled carts to be pulled overland by animals. 2 Sumerians also made advances in metalwork. In the fourth millennium B.C.E., metalworkers began to mix molten copper with tin, thereby producing a sturdier metal called bronze, which was used to make swords and shields for soldiers and sometimes knives and axes for farmers. Other innovations, too, are credited to Sumerians. They created a calendar based on cycles of the moon and a double-entry bookkeeping method. They devised a computation system based on segments of 12 and 60, still used now for dividing time into hours, minutes, and seconds. And they developed architectural and engineering skills to build palaces, temples, fortifications, and irrigation systems. Furthermore, as trade and tribute expanded and society grew more complex, Sumerians devised symbols to record financial and administrative transactions. As this system improved, they also used it to record rituals, laws, and legendary exploits of rulers such as Gilgamesh. This momentous invention, which we call writing, facilitated governance, enhanced commercial connections, and vastly aided the preservation and transmission of knowledge. Sumerians wrote by inscribing figures in wet clay, which hardened into tablets, some of which still exist today. They etched symbols from right to left, using wedgelike characters that scholars now call cuneiform. At first these were merely stylized pictures of people, animals, and objects such as carts, houses, baskets, and bowls. Eventually, however, as characters were added to express ideas and sounds, writing became very complex, so schools were set up in palaces and temples to train writing specialists, or scribes. Few Sumerians learned to write, but those who did played a key role in spreading and preserving their culture. So useful, indeed, was their writing system that it was adopted by outside conquerors seeking to unite and rule all Mesopotamia. Conquest was crucial in spreading Sumerian culture. Beginning around 2350 B.C.E., the Sumerian citystates were conquered by Akkadians, temporarily connecting the region under a common government. The Akkadians also established a pattern repeated throughout history: conquerors learned from societies they conquered and helped spread their culture. The Akkadians, for example, adopted the Sumerian calendar, writing system, and computation methods, introducing them to other regions as Akkad's empire expanded. Soon Mesopotamia’s central location led to the Akkadians being overthrown by nomadic invaders. The pattern of conquest and adaptation was repeated as the nomadic invaders briefly united Mesopotamia under the Babylonian Kingdom around 2000 BCE. Babylon's most notable ruler was Hammurabi, who reigned from 1792 to 1750 BCE and issued the famous law code bearing his name. Hammurabi 's code, sought to regulate matters such as trade and contracts, marriage and adultery, debts and estates, and relations among social classes. It assigned penalties based on retribution—the famous principle of "an eye for an eye"—attempting not only to deter crimes but also to limit retaliation by ensuring that punishments did not exceed the damage done. The code provides many insights into Mesopotamian society. It reveals, for example, that society was hierarchical, divided into nobles, commoners, and slaves, with different penalties depending on social status. A noble who knocked out another noble's tooth, for example, would have his own tooth knocked out ("a tooth for a tooth"), but a noble who knocked out a commoner's tooth only had to pay a fine. The code also shows that society was patriarchal, with men having greater rights and status than women. Marriages were contractual, arranged by the parents of the bride and groom. A husband could legally have a mistress, or even a second wife if his first one had no children. But a woman who cheated or ran off on her husband could be cast in the water to drown. Women did have some rights: they could buy and sell goods and own property, which they were allowed to inherit and pass on to descendants. For all his accomplishments, Hammurabi failed to establish an enduring regime. Following his death in 1750 B.C.E., the Babylonian kingdom declined and was eventually overrun by warlike nomads. 3 Egypt Political Geographic locations isolated Egypt from most outside invaders Peace allowed for the creation of a large and stable empire governed for a king called a pharaoh Pharaohs claimed to be gods living in human form giving them ownership and absolute rule of the land, power to establish a highly centralized authoritarian government, and mounted large-scale construction projects (like pyramids) to demonstrate power Pharaohs used authority to build large-scale irrigation projects to harness the regular annual floods of the Nile River and mount large military campaigns into surrounding regions Pharaohs were supported by an extensive bureaucracy made up of hundreds of ministers and priests, and tens of regional governors Government collected as much as 60% of farm harvests as tax and created a labor draft Economic The 4000 mile-long Nile River flooded annually and acted as the life blood of the civilization providing rich soil, fish, and papyrus Gov’t built irrigation led to food surpluses, population growth, and the division of labor The farming of wheat, barley, cotton, beans, and fruit trees could only occur in a six mile stretch of land that bordered either side of the Nile Egyptian skill with bronze and iron metallurgy helped keep the economy productive in this fragile environment and prevent invasion Specialized labor systems included farmers, craftsmen/artisans, metallurgists, political administrators, priests, and slaves Artisans skillfully used papyrus to make scrolls, river rafts, baskets, rope, and sandals Merchants were less important in Egypt but societies around the Mediterranean Sea sailed to Egypt to trade for their prized artisan goods and borrow ideas Social Regular controllable flooding and dependence on nature resulted in optimistic worldview and polytheistic religion of powerful gods Life seems dominated by a belief in the afterlife (mummies, frontal art) Powerful priests were members of the elite for their ability to read & write, honor the numerous deities, and commission temples & religion monuments built solely for the purposes of veneration Pictorial writing system, hieroglyphics, developed recording history, religious worship, and scientific understandings, but no epic literature developed Social classes dominated by ruling class and priests with a small nobility, large farming population, and large slave population, but there was some social mobility available through the bureaucracy Men dominate public and private life in a patriarchal system, though writings showed the importance of male/female relationships, rule by a few women, and laws allowing female rights of property ownership and divorce Became advanced in art & architecture, medicine, metallurgy – first bronze tools, and pottery. Although less advanced in math and astronomy, Egyptians developed a 365 day 12 month calendar in order to predict the Nile’s floods. 4 Egypt North Africa is dominated by the Sahara Desert, a hot, dry wasteland as large as the United States. Only the Nile River, flowing north through the desert, interrupts the arid expanse. Although some north Africans settled along the mild coastline, most North Africans, however, settled near the Nile River, where they clustered in farming villages along its fertile floodplains. These villages eventually formed the foundations of large, complex, dynamic societies later called Egypt. In the fourth millennium BCE, as the Nile Valley population grew, towns and villages along the river united into small kingdoms. These early states organized irrigation bringing river water to farm fields. By 3100 B.C.E., through various conflicts and conquests, the northern realms combined into a Kingdom of Egypt, which became one of the ancient world's most powerful and prosperous realms. In some ways, developments in Egypt paralleled those in Mesopotamia. As in Mesopotamia, smaller states combined by conquest into larger domains, with powerful rulers, polytheistic religions, writing systems, and extensive commerce. In other ways, however, Egypt differed markedly from Mesopotamia. Separated by seas and deserts from potential foes, and blessed by a river whose annual, soil-enriching floods helped farmers produce ample crops year after year – ancient Egypt was bountiful, powerful, extensive, and predictable, much like the Nile River. More stable and predictable, Egyptian society gradually developed belief in life after death, prompting efforts to preserve and house the remains of rulers and other prominent people. Central to Egypt's worldview was the concept that the universe's elemental order encompassed truth, justice, harmony, and balance. The rulers, called pharaohs, were powerful, godlike figures whose main duty was to maintain this order. The sun god and chief divinity ruled the heavens much as pharaohs ruled the earth. Religion and governance in Egypt were one and the same. Other popular gods became symbols of fertility, devotion, and the victory of life over death, inspiring an outlook far more hopeful than that of early Mesopotamian religion. Sustained by such myths and the cycles of the Nile, whose annual soil-renewing floods were more regular and predictable than floods in Mesopotamia, Egyptians concluded that life was renewable and cyclical. They came to believe that death was not the end of life, that honorable living would merit eternal life. Religion thus reinforced morality, as the prospect of attaining life after death promoted honorable behavior. The prospect of life after death also promoted mummification, an elaborate process for preserving the bodies of prominent people after death. Like the early Mesopotamians, ancient Egyptians made momentous contributions to culture, knowledge, and communication. They produced impressive artworks, decorating temples and tombs with splendid paintings and sculptures. They charted constellations, created a calendar, and practiced medicine based on natural remedies. They even invented an accounting system and developed mathematics to advance their architectural and engineering skills. Egyptians also devised a form of writing now called hieroglyphs. Like Sumerian cuneiform, it began in the fourth millennium BCE with pictographs, to which were added symbols for ideas and sounds. Like the Sumerians, Egyptians trained scribes to master and use their writing system. Unlike the Sumerians, however, Egyptian scribes wrote with ink-dipped reeds on papyrus, a paperlike material made from plants that grew along the Nile, and rolled it into scrolls for easy storage or transport. Far less cumbersome than Sumerian clay tablets, the scrolls helped Egyptians readily record their legends, laws, rituals, and exploits. Deciphered records reveal that Egypt had a high degree of political and social stratification. They also show that life focused mainly on family, farming, and the Nile. Egyptian society was structured by status and wealth. Upper classes of priests and state officials lived in luxury; middle classes of merchants, scribes, and artisans enjoyed some prosperity; and lower classes of peasants and laborers worked hard to 5 barely survive. Most Egyptians were peasants: humble farmers and herders raising wheat, barley, cotton, sheep, and cattle. Marriage and family were central to Egypt's society. Some men practiced polygyny, meaning they had more than one wife, but marriages were mostly monogamous. As in West Asia, husbands provided the homestead while wives brought a dowry and furnishings into the marriage. Gender roles were well defined but not rigid. In lower-class households men mostly worked the fields, but they might also be hunters, miners, craftsmen, or construction workers. Women mainly did household tasks, such as cooking and making clothes. But women in Egypt seem to have had higher status than those in West Asia. Egyptian women could own and inherit property, seek and obtain a divorce, and pursue trades such as entertaining, nursing, and brewing beer. Furthermore, in contrast to West Asian households, Egyptian families often were matrilineal, with property descending through the female line, and wives in Egypt were recognized as dominant in the home. Egyptian priestesses played key roles in religion, and a few women even served as rulers. But governance and warfare were, as elsewhere, mainly the work of men. The rhythm of work in Egypt followed the ebb and flow of the Nile, which typically flooded between July and September. In October, once the waters receded, the growing season began. Aided by oxen and other farm animals, peasants plowed fields and planted crops, then tended them, bringing buckets of water from irrigation canals. The harvest usually started in February, with women and children helping the men gather crops and thresh grain. The main crops were wheat and barley, but Egyptians also grew dates, grapes, and other fruits and vegetables. In years when food was abundant, the government stored some of the grain for use in times of scarcity. Large projects needing many workers, including construction and repair of palaces, temples, and irrigation systems, normally started once the harvest was over. Egypt's kings ruled a mostly peaceful and stable society. Internally they created a centralized state with an effective bureaucracy and tax collection system. Externally they established connections and traded with other societies, while largely avoiding warfare. Their most enduring achievements were the pyramids, monumental structures with triangular sides sloping upward toward a point. Around 1200 BCE, faced with new commercial and military challenges, Egypt's dominance waned, and power in northeastern Africa shifted to the south to the Kush of modern day Sudan. 6 China (Hwang He River, Shang dynasty) Political Like the Indus, the Hwang He is an unpredictable river, flooding often and earning the nickname “China’s Sorrow” Ancient dynasties are called the Xia and the Shang Little info survives on the Xia or how they ruled, whereas the Shang left written records. Shang rulers rely of corps of small, walled towns whose rulers recognize their authority. Shang rulers hand out food in exchange for military support, political advising or other skills that they can put to use (ex—metalworking) Elaborate tombs are created for rulers, which include thousands of objects as well as sacrificial victims (humans and animals) intended to serve the king in the next life Centralized government, power in the hands of the emperor Government preoccupied with flood control of the rivers Economic Steady annual rainfall meant the Chinese did not have to rely solely on irrigation systems Loose soil meant ironworking developed later here; most farmers used simple wooden tools Shank kings controlled natural resources like mines and used them to maintain power Little written info on trade with outsiders, but physical evidence shows overland trade route to India does exist Social Social classes consist of a small elite who control natural resources and a large majority who are poor farmers. There is also a sizable slave population and a smaller groups of artisans/craftsmen Women are viewed as inferior; limited to domestic roles (weaving, winemaking) Extended family system included veneration (worship) of ancestors System of writing appears on oracle bones (used to predict the future); other records which were written on bamboo or silk have been lost Myths and legends explain how civilization developed but organized religion does not play a large role Oracle bones used to communicate with ancestors Pattern on bones formed basis for writing system; writing highly valued, complex pictorial language with 3000 characters by end of dynasty Uniform written language became bond among people who spoke many different languages Bronze weapons and tools, horse-drawn chariots Geographical separation from other civilizations, though probably traded with the Indus Valley Job specialization —bureaucrats, farmers, slaves Social classes — warrior aristocrats, bureaucrats, farmers, slaves Patriarchal society; women as wives and concubines; women were sometimes shamans 7 India (Indus River Valley, Mohenjo Daro, Harappan) Political No evidence survives concerning the political system put in place (writings have not been translated and most physical evidence has been buried). Limited information, but large granaries near the cities indicate centralized control Scholars speculate that the two largest cities (Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro) may have been twin capitals Absence of large temples or palaces means that kings likely ruled from citadels in the heart of the city) Assumed to be complex and thought to be centralized Economic Irrigation/widespread farming develops by 3000BCE; development of large cities follows quickly Overland trade routes show evidence of trade to China and Mesopotamia (Pottery, tools and decorative items from the Indus Valley have been found in other parts of the world) Textile industry flourishes and centers around cotton production In addition to cotton, coppery, ivory and other luxury items are the most common exports Cities are arranged in grid-patterns, with broad streets and complex sewage systems (shows evidence of urban planning). Most homes have running water, showers and toilets. Social Lack of deciphered written records means we know little of how peoples lived Evidence of great wealth (jewelers, goldsmiths etc.) Variety of housing (from simple to extravagant) shows sharp class distinctions No large temples or palaces, so there may have been less emphasis on religion/ritual but likely focused on polytheism – naked man with horns the primary god; fertility goddesses Variety of human and animal figurines found at sites reflect a tradition of representational art; many figures show an emphasis on fertility & reverence for female reproductive function Toys, jewelry and other objects reflect a prosperous society with ample wealth and leisure time Writing system only recently decipherable Soapstone seals that indicate trade with both Mesopotamians and China Pottery making with bulls and long-horned cattle a frequent motif Cruder weapons than Mesopotamians – stone arrowheads, no swords 8