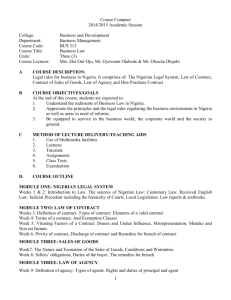

1. TITLE OF PROPOSED DISSERTATION:

advertisement