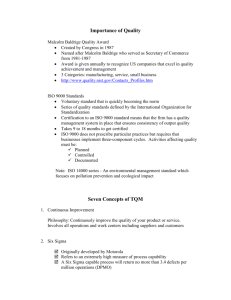

ST CLEMENTS UNIVERSITY SYSTEM

advertisement