Keeping College Affordable is Essential By Martha J. Kanter

advertisement

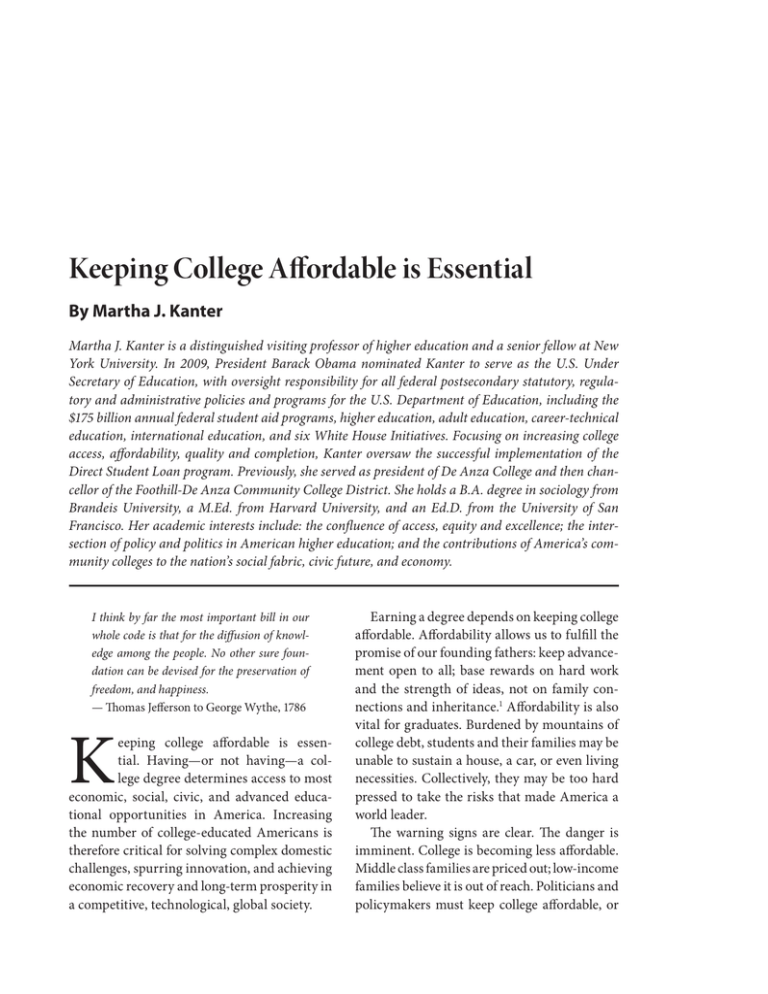

Keeping College Affordable is Essential By Martha J. Kanter Martha J. Kanter is a distinguished visiting professor of higher education and a senior fellow at New York University. In 2009, President Barack Obama nominated Kanter to serve as the U.S. Under Secretary of Education, with oversight responsibility for all federal postsecondary statutory, regulatory and administrative policies and programs for the U.S. Department of Education, including the $175 billion annual federal student aid programs, higher education, adult education, career-technical education, international education, and six White House Initiatives. Focusing on increasing college access, affordability, quality and completion, Kanter oversaw the successful implementation of the Direct Student Loan program. Previously, she served as president of De Anza College and then chancellor of the Foothill-De Anza Community College District. She holds a B.A. degree in sociology from Brandeis University, a M.Ed. from Harvard University, and an Ed.D. from the University of San Francisco. Her academic interests include: the confluence of access, equity and excellence; the intersection of policy and politics in American higher education; and the contributions of America’s community colleges to the nation’s social fabric, civic future, and economy. I think by far the most important bill in our whole code is that for the diffusion of knowledge among the people. No other sure foundation can be devised for the preservation of freedom, and happiness. — Thomas Jefferson to George Wythe, 1786 K eeping college affordable is essential. Having—or not having—a college degree determines access to most economic, social, civic, and advanced educational opportunities in America. Increasing the number of college-educated Americans is therefore critical for solving complex domestic challenges, spurring innovation, and achieving economic recovery and long-term prosperity in a competitive, technological, global society. Earning a degree depends on keeping college affordable. Affordability allows us to fulfill the promise of our founding fathers: keep advancement open to all; base rewards on hard work and the strength of ideas, not on family connections and inheritance.1 Affordability is also vital for graduates. Burdened by mountains of college debt, students and their families may be unable to sustain a house, a car, or even living necessities. Collectively, they may be too hard pressed to take the risks that made America a world leader. The warning signs are clear. The danger is imminent. College is becoming less affordable. Middle class families are priced out; low-income families believe it is out of reach. Politicians and policymakers must keep college affordable, or 24 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION an essential element of what makes America distinctive will vanish. A BRIEF HISTORY Education is by far the biggest and the most hopeful of the Nation’s enterprises. Long ago our people recognized that education for all is not only democracy’s obligation but its necessity. Education is the foundation of democratic liberties. Without an educated citizenry alert to preserve and extend freedom, it would not long endure. — President Truman’s Commission on Higher Education, 1947 A college education is critical to stimulating upward mobility. Centuries of Jesuit values and traditions, embodied in the admonitions of Pope Francis,2 and centuries of economic and social theory, culminating in the research of Thomas Piketty,3 inform this chapter. Education is key to a nation’s health and intergenerational success. Redirecting a fraction of the profits of our nation’s millionaires and billionaires to assuring “education for all” would sustain all of us, not just the middle class and the poor.4 For many years our nation possessed a different moral, civic, economic, and social character. FDR and the New Deal put many unemployed people to work in the recovery effort.5 Higher education grew and diversified, as America emerged from the Great Depression, though college still benefited the few. The economy expanded as veterans returned home and entered the workforce in droves after World War II. Colleges grew as ex-soldiers studied under the GI Bill, and as women demanded access to careers beyond the teaching and health professions. This increase in non-traditional populations, along with the academic and professional demands of privileged students, stirred an historic commitment to affordability. Beginning with the generous student aid provisions of the GI Bill, and building upon the nation’s optimism and social conscience, the Roosevelt, Truman, and Eisenhower administrations enacted and reauthorized several federal grant and scholarship programs. These programs ensured that low-income and middle class youth—not only the wealthy—could afford a postsecondary education.6 “Equal Opportunity for All”and freedom from racial and religious discrimination, stated President Truman’s Commission on Higher Education (1947), were essential components of a democratic society.7 Promoting the development of community colleges, the commission pressed states to subsidize tuition for the first two years of an undergraduate education. Public higher education was virtually free or provided at a low cost—$1.00 to $5.00 per credit hour—in most states, and colleges offered many full tuition scholarships. Stirred by the GI Bill, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the women’s liberation movement, community colleges and state universities expanded dramatically through the 1970s, providing opportunities for unprecedented numbers of low-income and middle class Americans. American higher education flourished. In 1965, Congress passed and President Johnson signed the Higher Education Act (HEA). The act focused on “support” and “improvement,” not on “disruption” and “reform”—today’s prevalent catchwords. The HEA included three major grant programs: the Economic Opportunity Grant (subsequently named the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant—BEOG—and later the Pell Grant), the National Defense Student Loan Program (originally enacted in 1958; later named the National or Federal Direct Student Loan Program—NDSL), and the Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (SEOG). The act also offered low-interest loan programs for students who did not meet the income eligibility requirements for financial aid. HEA enabled millions of non-traditional students—women, minorities, veterans, and KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL military deferred young men—to enter college during and after the Vietnam War years. In 1978, President Carter signed the Middle Income Student Assistance Act (MISAA), enabling families earning less than $25,000 annually to quality for Pell Grants. The act aimed at adding 1.5 million more students into our nation’s colleges and universities. Amendments permitted middle class and wealthy parents to borrow up to $3,000 for each child in college. President Clinton established two significant national service programs—AmeriCorps and Vista—a decade after A Nation At Risk underscored the significance of education for America’s prosperity and security. A drawnout battle between President Clinton and lenders resulted in removing their authority to distribute National Student Direct Loans. The President further enabled college affordability by signing the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, allowing families to deduct college tuition from their income tax payments. Today, the majority of Americans want a college education, and enrollments and attainments continue to climb (Figure 1).8 Many citizens and government officials see higher education as a civil right, but Congress has enacted no legislation recognizing that right. Instead, the Bush administration dismantled the larger civic and social purposes of American higher education. Policymakers emphasized workforce preparation and career training. They increased financial incentives, encouraged for-profit higher education, and established and expanded K–12 charter schools. The Bush administration permitted for-profit postsecondary institutions to fund 85 percent—later 90 percent—of their revenues with federal student aid. The GI Bill or private funds could provide the remaining ten percent. The proportion of career colleges among higher education institutions grew from eight to 13 percent between 2008 and 2012. After Congress reauthorized the Higher Education Opportunity Act in August 2008, Figure 1. Population, Age 25 and Over, by Educational Attainment, Various Years 1940 to 1962, and Continuous Years 1964 to 2013 Population in millions 250 Bachelor's Degree or Higher High School, Some College 200 Less than High School 150 100 50 0 1940 47 50 52 57 59 60 62 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 2000 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11 12 13 Year Source: U.S. Census Bureau, March Current Population Survey, 1947, 1952–2002; Annual Social and Economic Supplement to the Current Population Survey, 2003–2013; Census of Population, 1940–1980. 25 26 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION the Obama administration’s Department of Education sought to curb the unintended consequences of the use of federal funds. Hundreds of for-profit and some public institutions with low graduation and high default rates, the department found, left thousands of students burdened by unmanageable debt. During its first term, the Obama administration promulgated 13 program integrity rules that resulted in on-time payments for the majority of students who took out loans directly from the Education Department.9 The department’s effective actions to preserve college access and affordability led to dramatic growth in college enrollments. Undergraduate and graduate enrollments combined grew to nearly 16 million students between 1991 and 2001—an 11 percent increase. An additional 32 percent increase between 2001 and 2011 brought the total to 21 million Americans.10 Supporting growth for low-income students, President Obama called for dramatic increases to the Pell Grant program. In 2010, Congress passed and the President signed the Student Aid and Fiscal Responsibility Act (SAFRA).11 Pell Grants increased by more than $1,000 to $5,730, adjusted to inflationary increases, under the act.12 Fulfilling the promises of our nation’s founders and of the Truman Commission, the number of lowincome students using Pell Grants increased from six to nearly ten million between 2008 and the present, more than a 50 percent increase. The grants increased the number of students attending higher education from families earning $10,000 or less by more than 100 percent. Building upon President Clinton’s accomplishments, the recent redesign of the Direct Student Loan program provided federal loans directly to students, thereby cutting out the lenders.13 The government used the $68 billion saved to increase Pell Grants and to lower the federal deficit. A simplified federal loan and grant application (the “FAFSA”)14 eliminated nearly half the questions—another breakthrough that facilitated access to student aid.15 As more students took out loans, they encountered difficulties in paying a reasonable amount for college and in managing debt after graduation. These difficulties resulted in the current affordability controversy, which caused a rethinking of the purposes and delivery of federal, state, and institutional student aid. Sustaining educational opportunity remains a national challenge. MAJOR CHALLENGES Keeping college affordable depends on how our nation addresses no less than eleven major challenges: widening income disparity, the achievement gap, the under-education of U.S. adults, a frustrated teaching profession, waning of our global competitive advantage, rising college costs, fluctuating student aid, confusing price structure, marketing, quality, and eroding state investment. Growing Economic Inequality The gap between rich and poor in the U.S. and across the globe worsened substantially during the last decade.16 The richest one percent of Americans received 65 percent of the nation’s income growth from 2002 to 2007. That proportion increased to 95 percent since 2009, a period when “wages have stagnated while stocks and corporate profits have soared.”17 Economic inequality produces disheartening long-term consequences for less-educated Americans in the lower income quartiles. Approximately 80 percent of high-income students enroll in college, and more than half of our nation’s high-income students attain a college degree. By contrast, only 29 percent of lowincome students matriculate, and fewer than one in ten graduate.18 “Children born to families in the top income quintile have a four in ten chance of remaining in that income group, on into adulthood,” reported the Pew Charitable Trusts. “Likewise, children born to families in the bottom quintile have a four in ten chance of staying there.”19 Widening Achievement Gap The U.S. high school graduation rate increased from 71 percent to 78 percent between 1995 and 2010—the best rate in decades.20 But the college enrollment and graduation rates of non-white students have lagged behind the rates of their white peers for the last 50 years.21 Students from low-income families earn bachelors’ degrees at one-eighth the rate—nine percent vs. 75 percent—of their more advantaged counterparts by age 24.22 We now have, for the first time, a growing majority of non-white students in our elementary, middle, and secondary schools.23 We’ve made some progress in college entrance rates. Between 2003 and 2010, for example, the proportion of Hispanics entering college increased from 24 percent to 32 percent. But we must make more progress in educating this soon-tobe majority in the entire population. Educating More Adults Our nation will grow from 320 million to approximately 400 million residents by 2050.24 Today, about 93 million U.S. adults (47 percent) have little or no college education; 75 million function at or below basic literacy levels.25 These statistics are disturbing, but 47 percent represents a significant reduction from decades past. Returning veterans and more women— veterans and non-veterans—entered college in droves following World War II and in ensuing decades. By doing as well or better than privileged students already in college, these adults confirmed the Truman Commission’s contention that higher education for the middle class was a worthy goal.26 Subsequent actions undermined access to affordable postsecondary education for all Americans. One-third of our nation’s children are not prepared for kindergarten; many lag two or more years behind in reading by the 3rd and 4th grades.27 Too many children lack highly educated parents and other caring adults who could nurture their intellectual and physical development. Their absence jeopardizes the KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL pipeline extending through college, career, and adult life. The post-traditional adult population will provide two-thirds of college graduates between now and 2020. High school graduates will make up the remaining third.28 Increasing the proportion of college-educated adults, especially from underrepresented populations will, in turn, safeguard a higher quality lifelong education for future generations. A Frustrated Teaching Profession Keeping college affordable is key to producing and sustaining a vibrant, world-class teaching workforce. Far too many students now opt out of the teaching profession. Teachers report feeling unappreciated, undervalued, and constrained— even strangled—by the plethora of federal and state bureaucratic regulations, the metricizing of classroom instruction (too many tests), and low wages. They want better professional development, high quality data, and research enabling them improve their teaching and raise learning outcomes for increasingly diversified classrooms. Teachers are on the defensive in many political and policy fights, including tenure, seniority, retention, medical benefits, and pensions. These challenges drive too many Americans from a profession for which they initially had great interest, passion, and talent. The growing nonwhite student majority demands a teaching workforce that reflects the languages and cultures represented in our schools. Only 14 percent of K–12 teachers are Hispanic and/or African-American; two percent are African American males. These disparities affect the composition of our education workforce in non-cognitive and academic dimensions. Black male youth, lacking positive role models, are more likely to end up in prison than to graduate from college.29 The average cost to rehabilitate a young African American in prison begins at $50,000 annually. Congress and ultimately our nation’s taxpayers must bear the cost of prison construction and maintenance, apart from the human capital costs. 27 28 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION Global Competitiveness Ensuring college affordability has global consequences. A generation ago, the U.S. was first in the world in the percentage of adults with an associate’s or bachelor’s degree. But we were 16th in the world in 2009 in college attainment among young adults, ages 25 to 34 years old. We’ve made some progress since then, moving from 14th in 2012 to 11th now—tied with Israel. In this age group, 43 percent now hold an associate’s or bachelor’s degree. But by comparison, more than 50 percent of young adults in the top performers—South Korea, Japan, and Canada—are college graduates.30 President Obama calls this ranking “unacceptable, but… not irreversible.” 31 Our national goals must include restoring the U.S. to first in the world and sustaining our global status. A falling-off in degree production is not the only result of declining college affordability. A recent 24-country survey assessed adult competencies in literacy, numeracy, and problem solving in technology rich environments. These competencies are essential skills for success in the workplace and in social settings.32 The U.S. performs below the international average in all three areas (Figure 2). A lack of education and economic opportunity explains the wider gaps between the more and less proficient adults.33 Rising College Costs Average tuition at a public four-year college has increased by more than 250 percent in the last three decades. — U.S. Department of Education Cost data, research, policy debates, political conflicts, and media reports about the escalation of college costs have convinced many Americans that entering college will entail financial hardship, or will be impossible to afford. Measured in current dollars, college tuition and fees increased by 439 percent between 1984 and 2007, outpacing growth in other economic Figure 2. Adult Competencies: Percent of Adults in Top Two Proficiency Categories Percent 70 U.S. Average International Average 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 55–65 45–54 35–44 25–34 Age Source: M. Goodman, R. Finnegan, L. Mohadjer, T. Krenzke, and J. Hogan. Literacy, Numeracy, and Problem Solving in TechnologyRich Environments Among U.S. Adults: Results from the Program for the International Assessmant of Adult Competencies 2012: First Look (NCES 2014–008). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2013. KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL sectors. The cost of medical care, the sector showing the second largest increase, grew by 251 percent during that period. Median family income grew by only 147 percent, while the cost of living increased by 106 percent. Table 1 shows the average annual percentage increases in inflation-adjusted prices by decade.34 In 2012–13, a year at a four-year college, including tuition, room, and board, averaged $12,100 and $23,800 after grants and tax credits at public and private institutions, respectively.35 Scholarship funding, designed to offset college costs for the middle class, have declined for several decades. From the 1970s through the mid-1980s, Pell Grants covered more than two-thirds of the cost of attending a public university and just about all of community college tuition for low-income Americans. Today, these grants cover less than one-third of public university costs and less than half of community college costs.36 Nor has federal work-study funding kept pace with student need, demand, or inflation. The federal work-study appropriation decreased from $1.3 billion in 2002–03 to $978 million in 2012–13. Meanwhile, the number of qualified low-income students increased by more than 50 percent in just the past five years. Long waiting lists for work-study positions abound almost everywhere.37 Four programs garner major attention in the affordability discussion: the Pell Grants, the GI Bill, the student loan program, and the loan forgiveness program. Elements of each program were preserved through the last recession, but all suffered from more complexity and unintended consequences. Pell Grants are not entitlements, and advocates engage in a challenging annual fight to keep the grants available for low-income students and to align grant increases with inflation.38 The compromise: shavings off of the core program while adding discretionary funds to the base. The Obama Administration secured a Congressional commitment to increase the basic Pell Grant from $4,731 in 2008–09 to $5,730 for 2014–15 for students from families with no expected family contribution. But this 20 percent increase for the 80 percent of students attending public universities occurred when state reductions in public higher education funding averaged 20 percent or more. To make matters worse, for-profit institutions of higher education—13 percent of postsecondary enrollments—consume about 25 percent of Pell Grant funding. Thousands of students leave those schools due to their high costs, defaulting on their federal and private loans. For-profit institutions of higher education account for Table 1. Average Annual Percentage Increases in Inflation-Adjusted Published Prices, by Decade, 1984–85 to 2014–15 Tuition and Fees Tuition and Fees, Room and Board PrivatePrivate NonprofitPublic PublicNonprofitPublic Four-YearFour-YearTwo-YearFour-YearFour-Year 1984–85 to 1994–95 4.0%4.4%4.6%3.2%2.3% 1994–95 to 2004–05 3.04.02.22.73.0 2004–05 to 2014–15 2.23.52.52.12.8 Sources: The College Board, Annual Survey of Colleges; NCES, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). This table was prepared in October 2014. Notes: Each number shows the average annual rate of growth of published prices in inflation-adjusted dollars over a ten-year period. For example, from 2004–05 to 2014–15, average published tuition and fees at private nonprofit four-year colleges rose by an average of 2.2 percent per year beyond increases in the Consumer Price Index. Average tuition and fee prices reflect indistrict charges for public two-year institutions and in-state charges for public four-year institutions. 29 30 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION “31 percent of all student loans and nearly half of all loan defaults,” notes the U.S. Department of Education. “About 22 percent of student borrowers at for-profit colleges,” adds the department, “defaulted on their loans within three years, compared to 13 percent of borrowers at public colleges.” 39 The GI Bill remains intact. But neither the GI Bill nor Pell Grants are available year-round, so veterans and low-income students must seek other revenues to cover their educational costs in the summer. Predatory lenders and poor quality institutions with higher cost programs target veterans and low-income students, further contributing to the dropout and loan default problems. Student loans skyrocketed over the past decade—the result of rising college costs and loosened restrictions on eligibility. The majority of students are saddled with debt after graduation, $29,400 on average. Charges at high cost institutions, predominantly in the private non-profit and the for-profit sectors, inflate this average.40 Students at public institutions leave college owing an average of less than $15,000, and approximately 40 percent of all students leave without any debt.41 Loan forgiveness and consolidation strategies have leveraged, but have not curtailed the rising costs. The Pell Grant program and GI Bill, some observers assert, have become gateways to the loan program—far from the intent of grant programs aimed at low-income students and veterans. Too Many College Loan Programs The complexities of the Federal Student Loan Program also endanger college affordability. Subsidized and Unsubsidized Stafford Loans, PLUS Loans, and Perkins Loans have different eligibility conditions and terms, interest rates and consequences for non- or irregular payments. Many students—especially students also applying for private loans—have difficulties grasping these differences.42 Too many Americans feel their debt load is spiraling out of control, especially when added to home mortgages, car loans, and credit card debt. Compounding the problem, too many low-income adults do not or cannot take full advantage of the available higher education tax benefits. These benefits include the American Opportunity Tax Credit, the Lifetime Learning Credit, Tuition Tax Deduction Credits, 529 Plans, and interest deductions from student loans. About one in six Americans, notes a recent government report, did not apply for or use their tax benefits.43 Elected officials call for raising awareness about tax credits and income consolidation and repayment options. But financial aid officers report that far too many undergraduates lack the knowledge to make sophisticated decisions about paying for college. We sorely need more financial literacy at all levels of education. College Asset Savings accounts help lowincome families fund some college costs.44 But, to date, the federal and state governments have not executed sustainable plans that replicate or scale these accounts. The various higher education tax credit programs are a mystery to thousands of families who could benefit. In fact, elected officials continue to press for action on raising awareness about tax credits and income consolidation and repayment options. Confusing Sticker Prices, Net Prices, and Tuition Discounts Variability in pricing also affects college affordability. Colleges advertise the sticker price for tuition, which varies from year to year. But the majority of institutions use institutional, state, and/or federal student aid to discount this price.45 Further, in legislative budget processes, states can, and do, vary tuition for the public institutions they oversee.46 Families are justifiably confused and frustrated about the actual cost. Intensive Advertising and Marketing Tactics Most states base public institution funding on enrollment levels. For-profit institutions depend on federal funds to cover most operating costs and to assure profitability. The 7,000 institutions of higher education in the U.S. therefore bombard students and families with television, Internet, billboard, and print advertising and marketing. Recruiters and ads promise the American dream, because enrollments equal revenues in a fiercely competitive environment. But too many students and families receive inaccurate information about college affordability; the real costs are too often unknown or misrepresented. Varied Institutional Quality and Integrity Americans must make informed choices about where to invest their effort, time, and money, but quality assurance safeguards are often a mystery to the average family. How should families assess quality? Do these institutions undergo peer review? Are their accreditation and program review reports transparent and easy to understand? An agency approved by the U.S. Secretary of Education must accredit an institution for it to access federal student aid. Therefore, more than 4,500 of the nation’s 7,000 postsecondary institutions are regionally or nationally accredited.47 But do Americans know that the mission of regional and national accreditors is to ensure academic quality? Are they aware that the quality of accreditors varies, and that many policy makers and politicians question their validity and reliability? 48 Making public understanding even more difficult: rating and ranking systems proliferated over the past decade. Each system has unique characteristics that can confuse students and families wishing information about institutional quality. Paying for a college education is a challenge, but paying for a poor quality education that leaves students underprepared and with high debt is disgraceful. Eroding State Investment Compounding the college affordability challenge, the recession that began in 2008 restricted access when most states disinvested in higher education. “Over the decade from 1998–99 to 2008–09,” noted a 2012 report, “state appropriations as a share of institutional KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL revenues per student dropped from 49 percent to 34 percent in public research institutions; 56 percent to 43 percent in state colleges; and 64 percent to 57 percent in community colleges.” 49 On average, states removed 20 percent of institutional support.50 State funding of public institutions as a share of total revenue declined from 30.9 percent to 22.3 percent between FY 2003 and FY 2012 (Table 2).51 The result: tuition escalation across the country.52 Because of declining state support between 1998–99 to 2008–09, “the share of total institutional revenue from tuition rose from 25 percent to 32 percent in public research institutions; 33 percent to 43 percent in state colleges; and 22 percent to 27 percent in community colleges. The increases did not offset declining state support.” 53 Federal student borrowing increased from 68.1 percent to 77.4 percent of tuition revenue at public institutions during the same years.54 Most states continued to reduce their higher education budgets since 2009 (Figures 3 and 4). While 80 percent of students attend America’s Table 2. State Funding of Public Institutions as a Share of Total Revenue, FY 2003 to 2012 Fiscal Year Share of Total Revenue 2003 30.9% 2004 28.2 2005 27.4 2006 30.1 2007 27.5 2008 29.1 2009 28.7 2010 23.6 2011 23.2 2012 22.3 Source: Baylor and Bergeron, 2014, 2. 31 32 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION Figure 3. State Funding of Public Institutions, FY 2004 to 2012 Dollars (in billions) 80 $77.6 75 $72.5 $69.8 70 $68.9 65 $61.9 60 2004 2006 2008 2010 2012 Fiscal Year Source: Baylor and Bergeron, 2014, 2. open door public community colleges and state universities, retrenchment squeezed out millions of students and adjunct faculty. The causes included the fixed commitments of state finance obligations, such as Medicaid, and reluctance to raise taxes or redesign tax policy. These revenue declines led institutions to seek out external revenue streams and to cut costs severely. They also dramatically increased enrollments of full-paying out-of-state and international students, driving out state residents from community colleges and state universities.55 Educators, government officials, business leaders, philanthropists, and scholars are debating whether American higher education will remain a public good or become fully privatized.56 California and New York offer some bright lights. In 2011, Governor Cuomo and the New York legislature approved a five-year Compact for Public Higher Education for SUNY and CUNY. The compact authorized stable, predictable tuition increases of no more than $300 per year, while preserving access for lowincome students, absent a fiscal crisis.57 In 2012, California taxpayers approved Governor Jerry Brown’s ambitious program of investments in K–12 and higher education.58 Despite such exemplary state leadership, students and families bear the brunt of college costs by assuming larger public and private loans. Federal student loan debt is estimated at more than a trillion dollars, and about 50 percent of college students and families do not repay their loans on a regular basis.59 This alarming debt burden will place the sustainability of loan and grant programs under intense scrutiny when Congress reauthorizes the Higher Education Opportunity Act. But this process places the public and private sectors, elected officials, policy makers, education leaders, business CEOs, students, and taxpayers at odds, thereby producing incremental improvement, at best, to college opportunity and affordability. KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL Figure 4. Declining State Support for Higher Education, One-Year Percent Changes, FY 2012–13 Rhode Island 13.1% Illinois 12.1 North Dakota 10.4 Alaska 3.8 Texas 3.1 West Virginia 1.7 Maryland 0.6 Delaware 0.3 Hawaii 0.2 Nebraska -0.5 Utah -0.8 Indiana -1.0 Arkansas -1.3 Maine -2.1 New Jersey -2.5 Iowa - 2.6 Kentucky - 3.4 Montana -3.5 North Carolina -3.7 Idaho -4.1 Alabama -4.7 Massachusetts -5.3 New Mexico -5.7 Mississippi - 6.3 Vermont -6.4 Kansas -7.0 Minnesota -7.1 Missouri -7.1 New York -7.1 South Carolina -7.5 Oregon -8.0 South Dakota -8.7 Georgia -11.5 Ohio -11.8 Florida -12.0 Michigan -12.2 Connecticut -12.2 Wyoming -12.7 Wisconsin -13.3 Pennsylvania -13.4 California -13.5 Nevada -14.0 Oklahoma -14.5 Washington -14.5 Virginia -14.7 Tennessee -14.7 Colorado -15.4 Louisiana -18.5 Arizona -25.1 New Hampshire -39.4 -50 -40 -30 -20 -10 0 Percent Change Source: Center for Study of Education Policy, Illinois State University, Grapevine, 2011–12. 10 20 33 34 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION THE PATH FORWARD We must adopt these five priorities to keep college affordable: 1. Enact and implement College for All. 2.Redesign, combine and simplify federal, state and institutional student aid and education tax benefits. 3. Improve and ensure the quality of American higher education. 4.Implement smarter, leaner laws and regulations that strengthen higher education and protect consumers. 5.Improve and communicate consumer information via a sophisticated national campaign. To meet these challenges and close the persistent gaps plaguing our nation for decades, keeping a college education within reach for all Americans will yield significant intellectual, social, and economic dividends. Higher education, most scholars affirm, is key to individual and intergenerational success in work and in life.60 Scholarship continues to produce new knowledge that, in turn, generates new and expanded industries, creates valuable intellectual property, and increases family-sustaining wages and economic mobility for low and middle-income Americans. More education increases demand for K–12 teachers and college professors who our nation needs to assure high student achievement in the future. Our nation must address each challenge, close the gaps, and dramatically improve levels of educational attainment. Hiring, supporting, and retaining our best teachers and professors will show colleagues how to replicate and scale the best of what works in America’s classrooms. College may not be essential for all, but most Americans want and deserve a postsecondary education. We must keep college affordable for the top 100 percent of Americans seeking opportunity for themselves and their children. The scholarship and evidence is there. But tireless political will and bipartisan efforts will decide the fate of these priorities, so much needed for assuring the nation’s future. CONCLUSION Above all things I hope the education of the common people will be attended to; convinced that on their good sense we may rely with the utmost security for the preservation of a due degree of liberty. — Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, December 20, 1787 61 All of us—politicians, policymakers, taxpayers, and consumers—must decide whether to sustain higher education as a public good, while encouraging the public and private sectors to collaborate and compete on educational excellence. Keeping college affordable—critical to this decision—depends on the reauthorization of the Higher Education Opportunity Act. The revised law could afford every American an opportunity to gain access to and complete an affordable, quality postsecondary education. It could dramatically improve, realign, and simplify outdated, inefficient, and overlapping federal and state legislative, regulatory, and administrative authorities. College-educated Americans will lead healthier, happier, and motivated lives, as our nation’s founders envisioned; they will prosper socially, civically, and economically.62 Political gridlock—caused by the rise of the Tea Party, the dismantling of bipartisanship, and the spigot of uncapped campaign contributions—has stymied a dysfunctional Congress for five years. Americans label Congress as a “do-nothing” entity; public confidence is at an all time low.63 We could achieve the new agenda if our political parties find common ground and if oppositional scholars and policy makers can share ideas and collaborate.64 In 1947, the President’s Commission proposed the College for All concept. The Commission sought to “provide for free college attendance through the first two years, for all youth who can profit from such education,” and “eliminate racial and religious discrimination.” This concept is still relevant. Under College for All, our nation’s students and families will know the full cost of an undergraduate KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL education, and the amount owed after graduation. Families below the poverty line would incur minimal or no debt after college. Middle class students will afford the first two-years of college by moving grants, loans, work-study, and tax credits into a single structure, and by basing eligibility on a sliding income scale. College for All would reaffirm higher education as a public good, available to all Americans. Education, as our political, religious, and academic leaders have reminded us for centuries, is the best assurance of democracy and opportunity. student is $5,730 for the July 1, 2014 through June 30, 2015 award year. U.S. Department of Education, 2015; Congressional Budget Office, 2013. NOTES 20 1 “Laws for the liberal education of youth, especially of the lower class of people, are so extremely wise and useful, that, to a human and generous mind, no expense for this purpose would be thought extravagant.” Adams, 1776; Jefferson, 1806. 2 A recent teaching of Pope Francis: “The promise was that when the glass was full, it would overflow benefiting the poor. But what happens instead, is that when the glass is full, it magically gets bigger—nothing ever comes out for the poor.” Willis, 2013. 3 Piketty, 2014. 4 The Truman Commission developed a model aimed at sustaining a vibrant democracy: double college attendance by 1960; integrate vocational and liberal education. It proposed the College for All concept, seeking to provide for free college attendance through the first two years, “for all youth who can profit from such education” and to “eliminate racial and religious discrimination.” President’s Commission, 1947. 5 Taylor, 2008; Rose, 2009. 6 The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944. (June 22, 1944). Also known as the GI Bill, this legislation, signed by President Roosevelt, provided further educational opportunities for veterans. 7 President’s Commission, 1947. 13 U.S. Department of Education, 2015. 14 U.S. Department of Education, 2014f. 15 U.S. Department of Education, 2009; Sunstein, Simpler, 2013, 122-123. 16 World Economic Forum, 2014. 17 Piketty and Saez, 2012; Saez and Zucman, 2014. See also: Piketty and Saez, 2003. 18 Bailey and Dynarski, 2011; Isaacs, Sawhill, and Haskins, 2008. 19 Pew Charitable Trusts, 2012. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics, 2014a. 21 Ladson-Billings, 2006; Orfield, 2014; Reardon, 2011; Reskin, 2012. 22 U.S. Department of Education, 2013a; Mortenson, 2010. 23 U.S. Department of Education, 2013b. 24 U.S. Department of Commerce, 2013. 25 U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education, 2014; U.S. Department of Education, 2003. 26 President’s Commission, 1947. 27 Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012; Bassett, 2014. 28 Soares, 2013. 29 Toldson and Lewis, 2012; The Sentencing Project, 2013. 30 Organization for Economic Development (OECD), 2014. 31 32 In October, 2013, the OECD Secretary General released the findings of the International Survey of Adult Skills, a product of the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) in Brussels. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2013. 33 9 34 U.S. Department of Education, 2014c. 10 U.S. Department of Education, 2013. 11 SAFRA is part of the Affordable Care Act, signed into law by President Obama on March 30, 2010. 12 Pell Grant funding may change annually as a result of federal legislation. The maximum Pell Grant per eligible and Obama, 2010. 8 U.S. Census Bureau, 2014. Cooperation Allan, Grossman, Rivkin, and Vaduganathan, 2014. National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education, 8. 35 Baum and Ma, 2012. 36 CNN Wire Staff, 2012. 37 National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators, 2014. 35 36 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION 38 U.S. Department of Education, 2014d; New America Foundation, 2014. 39 63 Gallup, August 2014. See also Jones, 2014. 64 Goldrick-Rab and Kelly, 2014. U.S. Department of Education, 2014e. 40 REFERENCES McDonald and Brady, 2014. 41 Baylor and Bergeron, 2014. 42 Dynarski and Clayton, 2006. 43 Letter to U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, 2014. 44 Corporation for Enterprise Development, 2012; Elliott, Song, and Nam, 2013. 45 Levine, 2013. 46 Hiltonsmith and Draut, 2014. 47 U.S. Department of Education, 2014a; U.S. Department of Education, Institute for Education Sciences, 2013c. 48 Chingos, 2013; U.S. Senate, 2013. 49 American Council on Education, 2012, 4. 50 51 Oliff, Palacios, Johnson, and Leachman, 2013. Baylor and Bergeron, 2014, 2-4. 52 U.S. Department of Education, 2014b. See also U.S. Department of Education, 2009. 53 American Council on Education, 2012, 4. 54 Baylor and Bergeron, 2014, 2-4. 55 State Higher Education Executive Officers, 2012; Federal Reserve Bank of New York, 2012. “[F]rom 2000 to 2010, public funding per pupil, defined as state and local support for public higher education per pupil (excluding loans), fell by 21 percent.” Chakrabarti, Mabutas, and Zafar, 2012. 56 American Association Universities, 2013. 57 of State Colleges and Cuomo and Megna, 2014. 58 California Secretary of State, 2012. 59 “Federal Student Aid,” 2014; Board of Governors, 2014, Nasiripour, 2014. 60 Bowen, Chingos, and McPherson, 2009; Schneider, Martinez, and Owens, 2006; Schneider, Kirst, and Hess, 2003; Carnevale, 1999; Lazerson, 2010; Schneider and Stevenson, 1999. 61 Jefferson, 1787. 62 Gallup found that college graduates burdened with student debt are less healthy, happy, motivated, and financially secure than their peers over time. Dugan and Kafka, 2014. See also Cooke, Barkham, Audin, Bradley, and Davy, 2004. Adams, J. “Thoughts on Government” in idem., The Revolutionary Writings of John Adams, selected and with a foreword by C. Bradley Thompson (Indianapolis, Ind.: Liberty Fund, 2000 [1776]) . http://oll. libertyfund.org/titles/592. Allan, S., A. Grossman, J. Rivkin, and N. Vaduganathan, eds. Lasting Impact: A Business Leader’s Playbook for Supporting America’s Schools. Cambridge, Mass.: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, The Boston Consulting Group, and the Harvard Business School, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.hbs.edu/competitiveness/research/pk12-education/publications.html. American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Creating a New Compact Between States and Public Higher Education: A Report by the AASCU Task Force on Making Public Higher Education a State Priority. Washington, D.C.: AASCU, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.aascu.org/policy/P5/newcompact/fullreport.pdf. American Council on Education. Putting College Costs into Context. Washington, D.C.: ACE, April 5, 2012, 4. Retrieved from: http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/ Documents/Putting-College-Costs-Into-Context.pdf. Annie E. Casey Foundation, The. Double Jeopardy: How Third-Grade Reading Skills and Poverty Influence High School Graduation. D.J. Hernandez. Baltimore, Md.: Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/AECFDoubleJeopardy-2012-Full.pdf. Bailey, M.J., and S.M. Dynarski. “Inequality in Postsecondary Attainment,” in G. Duncan and R. Murnane, eds., Whither Opportunity: Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2011, 117-132. Bassett, M.D. Policy Brief Summer 2014: Considering TwoGeneration Strategies in the States. Chevy Chase, Md.: Working Poor Families Project, 2014.. Retrieved from http://www.workingpoorfamilies.org/wp-content/ uploads/2014/09/WPFP-Summer-2014-Brief.pdf. Baum, S. and J. Ma, Trends in College Pricing: 2012. New York: The College Board, 2012). Retrieved from: http://trends.collegeboard.org/college-pricing/ notes-sources. Baylor, E. and D. Bergeron. Public College Quality Compact for Students and Taxpayers: A Proposal to Reverse Declining State Investment in Higher Education and KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL Improve Quality and Affordability. Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress, 2014. Retrieved from: http://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/ uploads/2014/01/HigherEd-brief1.pdf. Cooke, R., M. Barkham, K. Audin, M. Bradley, and J. Davy. “Student Debt and its Relation to Student Mental Health.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 28 (1) (2004), 53-66. Board of Governors, Federal Reserve System. (Graphic illustration, delinquency rates). Charge-off and Delinquency Rates on Loans and Leases at Commercial Banks. May 20, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www. federalreserve.gov/releases/chargeoff/delallsa.htm. Corporation for Enterprise Development. “Policy Brief: College Saving Incentives. Assets and Opportunity Scorecard.” 2012. Retrieved from: http://cfed.org/ assets/scorecard/2013/pb_CollegeSavingsIncentives_2013.pdf. Bowen, W., M. Chingos, and M. McPherson, Crossing the Finish Line: Completing College at America’s Public Universities. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2009. Cuomo, A. and R.L. Megna. Building on Success: 2014–15 New York State Executive Budget. Albany, N.Y.: New York State Division of the Budget, January 21, 2014. Retrieved from: http://publications.budget.ny.gov/ eBudget1415/fy1415littlebook/HigherEducation.pdf. California Secretary of State, Debra Bowen. Statement of Vote—November 6, 2012 General Election. Sacramento, Calif.: Secretary of State, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.sos.ca.gov/elections/sov/2012-general. Carnevale, A.P. Education=Success: Empowering Hispanic Youth and Adults. 1999. Century Foundation, The. Bridging the Higher Education Divide: Strengthening Community Colleges and Restoring the American Dream. Baum, S., C. Kurose, S. Goldrick-Rab, P. Kinsley, T. Melguizo, and H. Kosiewicz. New York: The Century Foundation Press, 2013. Chakrabarti, R., M. Mabutas, and B. Zafar. Soaring Tuitions: Are Public Funding Cuts to Blame? New York Federal Reserve Bank Report. September, 2012. Retrieved from: http://libertystreeteconomics. newyorkfed.org/2012/09/soaring-tuitions-are-public-funding-cuts-to-blame.html#.VAZhO2RdWc0. Chingos, M.M. Need for Better Data Trumps Need for College Ratings. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, The Brown Center Chalkboard, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.brookings.edu/research/ papers/2013/11/06-better-data-for-college-ratingschingos. CNN Wire Staff. CNN Fact Check: Obama’s Student Aid Boast on the Mark. October 17, 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.cnn.com/2012/10/17/politics/factcheck-student-aid. College Board. Trends in Student Aid. New York: College Board, 2013. Retrieved from: http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/student-aid-2013-fullreport.pdf. Congressional Budget Office. The Federal Pell Grant Program: Recent Growth and Policy Options. Washington, D.C.: Congress of the United States, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/ files/44448_PellGrants_9-5-13.pdf. Dugan, A. and S. Kafka. “Student Debt Linked to Worse Health and Less Wealth,” Gallup Wellbeing (August 7, 2014) Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/ poll/174317/student-debt-linked-worse-health-lesswealth.aspx. Dynarski, S.M., and J.S. Clayton. The Cost of Complexity in Federal Student Aid: Lessons from Optimal Tax Theory and Behavioral Economics. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University, Kennedy School of Government and National Bureau of Economic Research, 2006. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/ list/hiedfuture/reports/dynarski-scott-calyton.pdf. Elliott, W., H. Song, and I. Nam. “Relationships Between College Savings and Enrollment, Graduation, and Student Loan Debt.” St. Louis, Mo.: Center for Social Development, Washington University in St. Louis, March, 2013. Retrieved from: http://csd.wustl.edu/ Publications/Documents/RB13-09.pdf. Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “Liberty Street Economics Blog Examines Student Loans and Soaring Tuition Costs,” Research Update 3 (2012), 1-2. Retrieved from: http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/research_ update/ru09_12.pdf. “Federal Student Aid: Office of the U.S. Department of Education.” Federal Student Aid Portfolio Summary (Data file) (2014). Retrieved from https://studentaid. ed.gov/about/data-center/student/portfolio. Gallup Organization, The. U.S. Economic Confidence Index (Weekly). (Graph illustration). August 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/poll/125735/ economic-confidence-index.aspx. Goldrick-Rab, S. and A.P. Kelly, eds. Reinventing Financial Aid: Charting a New Course to College Affordability. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard Education Press, 2014. Hiltonsmith, R., and T. Draut. The Great Cost Shift Continues: State Higher Education Funding after the 37 38 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION Recession. March 6, 2014. Retrieved from: http:// www.demos.org/publication/great-cost-shift-continues-state-higher-education-funding-after-recession. Isaacs, J.B., I. Sawhill, and R. Haskins. “Getting Ahead or Losing Ground: Economic Mobility in America.” Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 2008. Jefferson, T. State of the Union Address, 1806. Retrieved from: http://www.infoplease.com/t/hist/state-of-theunion/18.html. ______. “Letter to James Madison,” December 20, 1787. Retrieved from: http://www.let.rug.nl/usa/presidents/ thomas-jefferson/letters-of-thomas-jefferson/jefl66. php. ______. “Letter to John Adams,” November 25, 1816, in Lester J. Cappon, ed., The Adams-Jefferson Letters, 2 vols. (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina, 1959), 2: 496-7. Jones, J. “Partisanship Points to Tough Midterm Environment for Dems,” Gallup Politics (July 31, 2014). Retrieved from: http://www.gallup.com/ poll/174260/partisanship-points-tough-midtermenvironment-dems.aspx Ladson-Billings, G. “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in U.S. Schools.” Educational Researcher 35 (7) (2006), 3-12. Lazerson, M. Higher Education and the American Dream: Success and its Discontents. Budapest and New York: Central European University Press, 2010. Letter to U.S. Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, and U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Jack Lew. “12 Senators Urging Obama Administration to Raise Awareness of Higher Education Tax Credits.” Personal communication, August 17, 2014. Levine, P.B. Simplifying Estimates of College Costs. Washington, D.C.: The Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www. hamiltonproject.org/files/downloads_and_links/ THP_Mini_DiscPaper_Final.pdf. McDonald, P. and P. Brady. The Plural of Anecdote is Data (Except for Student Debt). Washington, D.C.: Hamilton Place Strategies, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.hamiltonplacestrategies.com/news/ media-coverage-student-debt. Mortenson, T. “Bachelor’s Degree Attainment by Age 24 by Family Income Quartiles, 1970–2009,” Postsecondary Education Opportunity, 21 (November, 2010). Retrieved from http://www.postsecondary. org/last12/221_1110pg1_16.pdf. Nasiripour, S. “Half of Federal Student Loan Borrowers Not Paying on Time.” Huffington Post, August 11, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.huffington post.com/2014/08/11/student-loans-delinquent_n_ 5670154.html?page_version=legacy&view=print& comm_ref=false. National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators. National Student Aid Profile: Overview of 2014 Federal programs. Washington, D.C.: NASFAA, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.google. com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web& cd=3&ved=0CC8QFjAC&url=http%3A%2F%2F www.nasfaa.org%2Fadvocacy%2Fprofile%2F2014_ National_Profile.aspx&ei=oUYsVLm3DbHLsAT 7rYLABg&usg=AFQjCNEv9L1h2qUqJLD5DSN FbpdkNGa4RQ&sig2=8j-28vu29SKL_tPhLkOjg&bvm=bv.76477589,d.cWc. National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics (2013). Retrieved from: http://tinyurl. com/no8w9mk. National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. Measuring Up 2008: The National Report Card on Higher Education (San Jose, Calif.: NCPPHE, 2008). Retrieved from: http://measuringup2008.highereducation.org/print/NCPPHEMUNationalRpt.pdf. New America Foundation. Federal Education Budget Project: Background and Analysis—Federal Pell Grant Program. Washington, D.C.: New America Foundation, 2014. Retrieved from: http://febp.newamerica.net/ background-analysis/federal-pell-grant-program. Obama, B. “Speech at Gregory Gym.” Lecture conducted from University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas, August 9, 2010. Retrieved from http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2010/08/09/president-obama-highereducation-austin-we-are-not-playing-second-place. Oliff, P., V. Palacios, I. Johnson, and M. Leachman. Recent Deep State Higher Education Cuts May Harm Students and the Economy for Years to Come. Washington, D.C.: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.cbpp.org/ cms/?fa=view&id=3927. Orfield, G. “Tenth Annual Brown Lecture in Education Research: A New Civil Rights Agenda for American Education.” Educational Researcher, 43 (6), (August, 2014), 273-292. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Education at a Glance 2014: OECD Indicators. Brussels: OECD, 2014. Retrieved from: http:// dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2014-en. ______. Survey of Adult Skills. Brussels: OECD, 2013. Pew Charitable Trusts. Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility Across Generations. July, 2012. Piketty, T. Capital in the 21st Century. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, Belknap Press, 2014. ______. “Top Incomes and the Great Recession: Recent Evolutions and Policy Implications.” (Oct. 26, 2012, draft) 13th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, November 8–9, 2014. ______ and E. Saez. “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913–1998,” Quarterly Journal of Economics. Tech. 1st ed. 118 (2003). Retrieved from: http://eml. berkeley.edu/~saez/pikettyqje.pdf. President’s Commission on Higher Education. Higher Education for American Democracy. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1947. Reardon, S.F. “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap Between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations.” Whither Opportunity, 2011, 91-116. Reskin, B. “The Race Discrimination System.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (2012): 17-35. Rose, N.E. Put to Work: The WPA and Public Employment in the Great Depression, 2nd ed. New York: Monthly Review Press, 2009. Saez, E., and G. Zucman. “The Distribution of U.S. Wealth, Capital Income and Returns Since 1913.” March, 2014. Retrieved from: http://gabriel-zucman.eu/files/SaezZucman2014Slides.pdf. Schneider, B., M. Kirst, and F.M. Hess. “Strategies for Success: High School and Beyond.” Brookings Papers on Education Policy (2003), 55-93. ______ and D. Stevenson. The Ambitious Generation: America’s Teenagers Motivated, but Directionless. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1999. Sentencing Project, The. Report of The Sentencing Project to the United Nations Human Rights Committee Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System. 2013. Retrieved from: http://sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/rd_ICCPR%20 Race%20and%20Justice%20Shadow%20Report.pdf Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, The. June 22, 1944. Copy at: http://research.archives.gov/description/ 299854. Also known as the GI Bill, this legislation signed by President Roosevelt provided further educational opportunities for veterans. KEEPING COLLEGE AFFORDABLE IS ESSENTIAL Soares, L. Post-traditional Learners and the Transformation of Postsecondary Education: A Manifesto for College Leaders. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www. acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/Post-traditional-Learners.pdf. State Higher Education Executive Officers (SHEEO). State Higher Education Finance, 2012 (Boulder, Colo.: SHEEO, 2012). Sunstein, C. Simpler. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2013. Taylor, N. American-Made: The Enduring Legacy of the WPA, When FDR Put the Nation to Work. New York: Bantam Books, 2008. Toldson, I.A. and C.W. Lewis. Challenge the Status Quo: Academic Success among School-age African American Males. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Black Caucus Foundation, Inc., 2012. Retrieved from: http://www.cbcfinc.org/oUploadedFiles/CTSQ.pdf. Truman, H.S. “Statement by the President Making Public a Report of the Commission Higher Education,” December 15, 1947. Retrieved from http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=1852. U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau, 2012 National Population Projections: Summary Tables, Table 1. Retrieved from: https://www.census.gov/population/projections/data/national/2012/ summarytables.html. ______. American FactFinder Monthly Population Estimates for the United States: April 1, 2010 to December 1, 2014, 2013 Population Estimates. Retrieved from http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. ______. “Population Age 24 and Over by Educational Attainment: 1940–2013.” CPS Historical Time Series Tables, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.census. gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/historical. U.S. Department of Education. 2008–2009 Federal Pell Grant Program End-of-Year Report. Washington, D.C.: Office of Postsecondary Education, 2009. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/finaid/prof/ resources/data/pell-2008-09/pell-eoy-08-09.pdf. ______. The Database of Postsecondary Institutions and Programs (data file). Washington, D.C.: June, 2014a. Retrieved from: http://ope.ed.gov/ accreditation/GetDownLoadFile.aspx, and http:// www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/index.html. ______. Federal Pell Grant Program Payment Schedule for Determining Full-time Scheduled Awards for 39 40 THE NEA 2015 ALMANAC OF HIGHER EDUCATION the 2014–2015 Award Year. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2014b. Retrieved from: https://www.ifap.ed.gov/dpcletters/attachments/2014 2015PellGrantPaymentandDisbursementSchedules. pdf. Washington, D.C.: NCES, 2014a. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014391.pdf. ______. Federal Student Aid, 2015. Retrieved from: https:// studentaid.ed.gov/types/grants-scholarships/pell. ______. “NCES Fast Facts: Postsecondary Enrollment Rates (2013)” in Digest of Education Statistics, 2012 (Washington, D.C.: NCES, 2014b), chapter 3. Retrieved from: http://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display. asp?id=98. ______. “Federal Student Loan Portfolio,” 2014c. Retrieved from: https://studentaid.ed.gov/about/data-center/ stu-dent/portfolio. ______. Racial and Ethnic Historical Trends. Washington, D.C.: NCES, 2013b. Retrieved from http://nces. ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_203.50.asp. ______. Free Application for Federal Student Aid. 2014f. Retrieved from: https://fafsa.ed.gov. ______. “Total Fall Enrollment in All Postsecondary Institutions Participating in Title IV programs and Annual Percentage Change in Enrollment, by Degree-Granting Status and Control of Institutions: 1995 through 2012” in Digest of Education Statistics. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2013c, Table 303.20. Retrieved from: http://nces. ed.gov/programs/digest/d13/tables/dt13_303.20.asp. ______. “Obama Administration Announces Streamlined College Aid Application.” June 24, 2009. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/news/pressreleases/2009/06/06242009.html. ______. Obama Administration Takes Action to Protect Americans from Predatory, Poor-Performing Career Colleges. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2014e. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/news/ press-releases/obama-administration-takes-actionprotect-americans-predatory-poor-performing-ca. ______. Student Financial Assistance: Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Request. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2014d. Retrieved from: http:// www2.ed.gov/about/overview/budget/budget15/ justifications/q-sfa.pdf. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. 1992 National Adult Literacy Survey and 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2003. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/naal/kf_demographics.asp#2. ______. The Condition of Education 2013. Washington, D.C.: NCES, 2013a. Retrieved from http://nces. ed.gov/pubs2013/2013037.pdf ______. Public High School Four-Year On-time Graduation Rates and Event Dropout Rates: School Years 2010–11 and 2011–12: First Look, NCES 2014-391. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Career, Technical and Adult Education. FY 2015 Budget Request. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2014. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/overview/ budget/budget15/justifications/o-ctae.pdf. U.S. Senate. Full Committee Hearing—Accreditation as Quality Assurance: Meeting the Needs of 21st Century Learning. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Senate, December 12, 2013. Retrieved from: http://www.help.senate.gov/ hearings/hearing/?id=ac694134-5056-a032-52005c2409df2cb5. Willis, O. “Pope Francis Rebukes ‘Marxist’ Attack From Rush Limbaugh and Conservative Media.” MediaMatters (Interview with La Stampa). December 15, 2013. Retrieved from: http://mediamatters.org/ blog/2013/12/15/pope-francis-rebukes-marxistattack-from-rush-l/197273. World Economic Forum, Outlook on the Global Agenda. “Top 10 Trends of 2014: 2. Widening Income Disparities,” 2014. Retrieved from: http://reports. weforum.org/outlook-14/top-ten-trends-categorypage/2-widening-income-disparities.