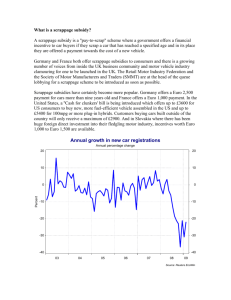

The Incidence of Cash for Clunkers Germany I

advertisement