Benjamin Harris, Eugene Steuerle, and Caleb Quakenbush Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center

advertisement

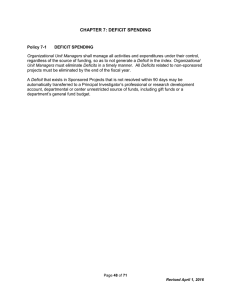

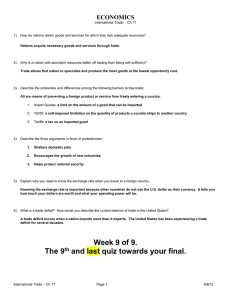

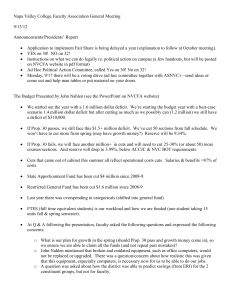

TODAY’S UNSUSTAINABLE BUDGET POLICY: A RECOUNT Benjamin Harris, Eugene Steuerle, and Caleb Quakenbush Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center January 30, 2013 ABSTRACT Although the recently passed American Taxpayer Relief Act instituted meaningful deficit reduction relative to previous policy, it still left the budget a far distance from any sustainable path. Under a plausible scenario, deficits never fall below 3.4 percent of GDP and rise to 5.4 percent of GDP by 2022. Given this baseline, an additional $150-$300 billion of annual deficit reduction, instituted after the economy has fully recovered, would put the budget on a stable path in the intermediate term while allowing for continued economic recovery. Yet even that path leaves longer-term budget problems unresolved. Without a more far-reaching agreement over such long-term issues, policymakers may have limited leeway to respond to new emergencies and meet the demographic pressures of the forthcoming decade. TODAY’S UNSUSTAINABLE BUDGET POLICY: A RECOUNT Although the American Taxpayer Relief Act raises taxes by about $600 billion over 10 years relative to previous policy, it still leaves the United States a far distance from any sustainable path. Under a plausible scenario, deficits never fall below 3.4 percent of GDP in the next few years and rise to 5.4 percent of GDP by 2022—in essence, a reversion to prior policy with somewhat higher tax revenues. Cutting the deficit by about $150 billion a year between 2015 and 2018, and by $300 billion a year thereafter, would theoretically put the budget on a stable path in the intermediate term while allowing for continued economic recovery. Yet, unless longer-term budget problems are tackled, even that path leaves little room to respond to any new recession or emergency, puts discretionary spending at or below a multidecade low, squeezes most programs for children and investment, and leaves the country unprepared for the further demographic and health cost pressures of the forthcoming decade. Deficit Reduction after the American Taxpayer Relief Act To the relief of many, Congress passed the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) on December 31, 2012, avoiding most scheduled expirations of various tax cuts while implementing a twomonth stay on steep discretionary spending cuts, which are typically referred to as the sequester. This deal, which forestalled the vast bulk of the “fiscal cliff,” added $4.0 trillion to the 10-year deficit when measured relative to a current law with all those scheduled tax increases, but it subtracted $620 billion from the deficit when measured relative to ongoing policy.1 Faced with a fundamental trade-off between immediate deficit reduction and short-term macroeconomic stability, Congress chose the latter, effectively pushing most difficult deficit-reduction choices to another time. ATRA avoided steep increases in tax payments by permanently extending several ongoing tax cuts that had been scheduled to expire, many of which had been extended annually, sometimes retroactively.2 The alternative minimum tax patch was indexed permanently to inflation, preventing another 30 million taxpayers from almost immediately having to pay the tax. Income tax cuts originally enacted during the Bush administration were extended for taxpayers with incomes below $450,000 if married and $400,000 if single. The estate tax rate was set at 40 percent, while the per person exemption was set at $5 million and was indexed to inflation. Several more moderate tax cuts were extended for less than 10 years. Regular extenders, such as the deduction for state and local sales taxes paid and the research and experimentation 1 The Congressional Budget Office score of the bill, released January 1, 2013, is available here: http://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/American%20Taxpayer%20Relief%20Act.pdf. 2 A more complete description of ATRA’s provisions is available here: http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/412730-Tax-Provisions-in-ATRA.pdf. 1 (or R&E) tax credit, were continued for 2013 only. Refundable tax credits established under 2009 stimulus legislation, such as an expansion of the Hope tax credit into the American Opportunity tax credit, a modest expansion of the earned income tax credit, and the extension of a child credit to lower income levels, were extended for five years. Several tax cuts were not extended. Taxpayers above the $400,000/$450,000 threshold will pay statutory tax rates that existed under the Clinton administration, before the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts. A 2 percentage point payroll tax cut, widely envisioned as temporary, was also allowed to lapse. On the spending side, ATRA did little more than suspend the scheduled sequester of domestic discretionary and defense spending for two months by lowering the amount of sequestered funds for fiscal year 2013 by $24 billion. (This was partially offset by later cuts in discretionary spending and by a budget gimmick related to Roth retirement accounts that allows retirement savers to prepay tax liability at a long-term loss to the Treasury.) ATRA also delayed for one year large scheduled cuts in physicians payments under Medicare, a routine practice by policymakers often referred to as the “doc fix.” By making many tax provisions permanent, ATRA addressed several long-standing tax policy questions, but it did little to address budget uncertainty. Seemingly overnight, the lingering tax policy uncertainty that had plagued the policy arena since 2001, when tax cuts enacted then were scheduled to expire, was transformed into spending uncertainty. As of January 2013, Congress is staring down numerous debt ceiling extensions, the scheduled implementation of the first stage of a sequester, and the expiration of the continuing resolution—the legislation authorizing funds for the federal government to continue its operations. In addition, the “doc fix” is scheduled to expire at the end of the year. Deficit reduction relative to past policies was primarily achieved through higher taxes on households above the $450,000/$400,000 threshold. These households will see their income taxes rise to Clinton administration levels and their tax rates on capital gains and dividends will rise to 20 percent (in addition to the scheduled surtax enacted through the Affordable Care Act). Deficit Reduction under ATRA A congressional failure to pass legislation bypassing the fiscal cliff would have put the United States on a path to a sudden, very large deficit reduction that would have almost certainly ensured the onset of a moderate to severe recession. Deficit reduction and the government component of economic growth are unavoidably opposite sides of the same coin. Without action and before taking account of the impact on the economy, the deficit as a percentage of the economy would have plummeted from 7.0 percent in 2012 to 4.0 percent in 2013 and 0.4 percent in 2018, before inching upward for the remainder of the budget window. 2 Steep and severe cuts in government spending combined with rapid increases in tax revenues, however, would have made near-term economic growth nearly impossible, leading again to very large deficits. Since 1970, the largest single-year reduction in the deficit as a share of GDP was 1.8 percent, and the most rapid five-year reduction was 3.8 percent (which coincided with swift economic expansion at the end of the 1990s). The levels under previous law would have exceeded both. The limited deficit reduction under ATRA (never more than 1 percentage point of GDP in any year after the economy is assumed to recover) in the short term, therefore, allows the tepid recovery to continue and hopefully expand toward stronger economic growth. On the flip side, the law in place post ATRA, now the new “current law,” represents toolittle deficit reduction given long-term budget pressures. According to our analysis, current-law deficits will drop to 6.1 percent of GDP in 2013 and 2.6 percent of GDP in 2018, before rising steadily through 2022. Such a deficit-reduction path would represent meaningful progress, but the fairly large and growing deficits toward the end of the 10-year budget window demonstrate that even this path leaves quite inadequate adjustments for the growing demographic and health care cost pressures that continue to accelerate. 8 Federal Deficits under Three Budget Assumptions (percentage of GDP) 6 Post-ATRA current policy ATRA 4 2 Previous law 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Source: Authors' calculations from CBO data. 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 Unfortunately, as before ATRA was enacted, a “current law” deficit reduction path is not meaningful because it does not reflect past policymaking behaviors that lawmakers are likely to repeat. Congress failed to address several ongoing polices that will likely require attention in 2013. Among the principal items that current law requires, but that no one fully expects to happen, are a fairly severe cut in defense and domestic discretionary spending under sequestration, the expiration of the “doc fix” in 2013, and the expiration of some refundable credits benefiting lower-income taxpayers in 2017. Removing these and other related sources of deficit reduction leads to a more realistic assessment of a “plausible current policy scenario” 3 (table 1).3 Deficits fall from 6.4 percent of GDP, or $1.015 trillion in 2013, to 3.4 percent of GDP in 2017, then start on another upward path throughout the remainder of the projection period. Such a deficit path maintains many of the economic pitfalls associated with high budget deficits and public debt, as well as a weakened ability to respond to any new recession, foreign crisis, or other emergency. Current Policy under ATRA Subject to Floors in Discretionary Spending (percentage of GDP) 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 Defense discretionary 4.3 4.1 3.8 3.5 3.3 3.1 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 Domestic discretionary 4.0 3.8 3.9 3.7 3.5 3.3 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 3.2 Mandatory 13.2 13.6 13.5 13.4 13.6 13.4 13.4 13.6 13.9 14.1 14.5 Net interest 1.4 1.4 1.5 1.5 1.8 2.2 2.7 3.0 3.3 3.5 3.7 22.9 22.9 22.7 22.1 22.2 22.1 22.2 22.8 23.3 23.8 24.4 Total outlays 15.7 16.3 17.8 18.4 18.6 18.8 18.7 18.7 18.8 18.9 19.0 Revenue -7.3 -6.5 -4.9 -3.7 -3.5 -3.4 -3.5 -4.1 -4.5 -4.9 -5.4 Deficit (-) Source: Authors’ calculations. Preparing for the Future The budget outlook remains treacherous. Three notable “cliffs” or obstacles require resolution in the near future and potentially many times thereafter: the continuing points of exhaustion of borrowing authority by Treasury associated with running into debt ceilings; the effective implementation of sequesters, the first occurring in spring 2013; and the expiration of various continuing resolutions. While these events all constrain government spending in some fashion, they do so in very different ways and with dramatically different consequences. If Congress does not increase the Treasury’s authority to borrow, the government could lose the ability to pay its bills, including Social Security payments, interest payments on Treasury bonds, and government worker salaries. The financial system would be in chaos, and interest rates would likely spike to an unprecedented level. Economic growth would plummet. 3 Many of the differences between current law and current policy here are similar to those of CBO in its alternative fiscal scenario and the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB). We especially thank the latter for allowing us to review and use several of their calculations in the period before CBO’s February 2013 update. CFRB analysis of the fiscal cliff can be found here: http://crfb.org/blogs/good-bad-and-ugly-fiscal-cliff-package. Our primary difference with CBO (under an estimated update) and CRFB is that we assume that domestic discretionary and defense discretionary will not continue falling below their multidecade lows of 3.0 percent of GDP and 3.2 percent of GDP, respectively. We have also included in current policy the so-called extenders (excluding bonus depreciation) that are routinely adopted year after year, as does CBO but not always CFRB. Like CRFB, we assume a faster war drawdown. 4 The effects of the other two obstacles are more subtle. A failure to address the sequester would result in crude cuts in defense and nondefense discretionary spending, in addition to some mandatory programs like Medicare. Some federal employees would be furloughed; many agencies would stop hiring if they have not done so already. The cuts would be arbitrarily applied, with little or no adjustment for policy concerns. The effects of an expired continuing resolution would be more severe. The federal government would not be able to authorize spending for discretionary programs, and nonessential government services would shut down. Reverberations would be felt in the wider economy but would be much less severe relative to the exhaustion of Treasury borrowing authority. While potential short-term crises abound because of these arbitrary cliffs, they can be avoided somewhat easily by simply ending that type of policymaking. Unfortunately, long-run demographic and health spending pressures still persist and threaten to cause real budget problems in the future, regardless of any cliffs. Ten-year budgets mask the even tougher period coming in the 2020s, at least when it comes to demographics and health care costs. The latter will be growing off an even larger base, while baby boomers will begin to swell the number of those reliant upon Social Security toward 30 percent of the adult population. Moreover, the baby boomers will start moving into their mid-70s and beyond, when health, long-term care, and other needs rise. These longer-term concerns differ fundamentally from the short-run crisis of today; their movements are slow, yet inexorable, and at rates faster than the economy and revenues are growing. If current beneficiaries are protected, however, reform can only gradually slow that growth rate. Today we have ample warning about the magnitude of these budget shortfalls: CBO’s most recent long-run outlook shows deficits of 7.7 percent of GDP and public debt at nearly 200 percent of GDP in 2037. Turning back to the intermediate term, and ignoring politics, Congress can set a deficitreduction path that does not overburden the continued recovery, while also establishing a framework for long-run deficit reduction. A minimal guiding principle for congressional budgeting in normal times, and absent automatic growth in mandatory programs like health and retirement, is to achieve primary account balance—that is, balancing the budget outside of interest payments—when the economy has recovered and is at full employment. Achieving this path for the intermediate term would be difficult but not insurmountable. The chart below shows the gap between the current policy deficit and interest payments—the amount needed to achieve primary balance. Congress could gradually reach this path over the 5 next several years by, for example, cutting the deficit $150 billion relative to current law for each year between 2015 and 2018, and $300 billion in each year thereafter.4 Still, absent dealing with longer-term pressures, even that type of reform is likely unsustainable. As long as so much spending growth is built into the budget indefinitely, the country will simply go from fighting one deficit battle to the next. Programs for children, investment, and other projects become further squeezed, while little or no room remains to deal with new recessions or emergencies. The suggested intermediate-term deficit-reduction path implies moderate spending growth, but if all that spending is determined by past laws, then there is little or no ability to deal with any new requirement or pressure on the economy without more deficit spending or deficit reduction. The bottom line is, we have a long way to go. Primary Deficit under Three Policy Scenarios (percentage of GDP) 6 5 4 3 2 Current policy 1 Current law Proposed reduction 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 -1 Source: Authors' calculations from CBO data. Notes: Primary deficit is total deficit excluding net interest payments. "Proposed reduction" assumes $150 billion in deficit reduction relative to current policy between 2015 and 2017, and $300 billion thereafter. 4 The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) makes a similar argument, claiming that $1.4 trillion in deficit reduction—$1.2 trillion in direct cuts and $200 billion in interest saving—will stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio. CBPP’s brief is available here: http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3885. 6