Barren County Middle School iLearn@Home 7 Grade Social Studies

advertisement

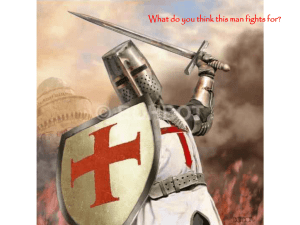

Barren County Middle School iLearn@Home 7th Grade Social Studies Day 2 Choose one of the options below to complete as your classwork for this snow day. Option 1: 1. Log in to Barren County Schools website and click on Barren County Middle School. 2. Go to Teacher websites. Click on my name. 3. On my page, click the iLearn@Home link or my google classroom link. 4. In google classroom, locate iLearn@Home day 2 and complete. 5. Be sure to use the graphic organizer at the end of this packet to summarize the articles. Option 2: 1. Read the attached articles. 2. Summarize the articles using the Who, What, Where graphic organizer at the end of the packet. Contact information should you need extra help. If your teacher does not reply or is not available, please email on of the other teachers. delenia.alls@barren.kyschools.us nicholas.pace@barren.kyschools.us jennifer.toms@barren.kyschools.us The when, where and who (of crusading) Setting a timeline In some ways, setting a beginning date for the crusading movement is relatively easy. The First Crusade was preached by Pope Urban II in 1095. Several different expeditions responded to this appeal, but the general dates for the First Crusade are 1096-1099, when the city of Jerusalem was conquered. Keep in mind though that crusading didn’t emerge from a vacuum, and many of the elements of crusading were circulating before 1095. However, finding an end date for the crusades is quite difficult indeed. Scholars used to stress that the heyday of crusading was before 1300. But we now know that crusading continued to flourish—as an ideal even when not in practice—for many centuries after that. Some place the end date at 1571, when the rising Ottoman Empire defeated the Kingdom of Cyprus at the city of Famagusta. Others place it in the late nineteenth century, when the last attempt at a military order (i.e., a Catholic armed religious order, like the medieval Knights Templar) ended. The argument can be made—and is in fact made by some groups around the world—that the crusades never ended at all. Theaters and targets The First Crusade was launched at the Levant (the region at the end of the eastern Mediterranean) with the stated purpose of rescuing Christians and bringing the Christian holy places—specifically Jerusalem—back into (European) Christian hands. Of all the crusades to the region, the First was the most successful (from the perspective of European participants), and led to the creation of small polities in the Levant, known as the crusader states. European nobles first governed these small states, which were inhabited by some settlers from western Europe as well as native Christians, Jews, and Muslims. By the time the Second Crusade rolled around (11461149) crusading had already expanded dramatically. The Second Crusade took place on three fronts: against Muslims in the Levant, against pagans in northern Europe, and against Muslims on the Iberian peninsula (modern day Spain and Portugal). This does not mean that all three fronts were coordinated, as in a modern war. Rather, it means that contemporaries believed that the wars on all three fronts together constituted a larger endeavor. We should also remember that the Levant and Iberia contained any number of local Christians, Jews, and other religious groups, and they were not always exempted from crusader violence, even though it was held to be wrong to persecute or kill fellow Christians and Jews. After the Second Crusade, crusading continued to expand and evolve. Muslims (or areas under Muslim governance) continued to be targets, especially when they threatened or reconquered portions of the crusader states, but other targets included Christian “heretics” (for example, in southern France), the Christian Byzantine Empire, and political opponents of the papacy within Europe. Crusading also developed local traditions. In northern Europe, crusading became a festive seasonal rite of passage for western European knights, complete with honorary feasts and prizes. In other places, crusading interacted with pre-existing factors, for example in Iberia, where both ideas of crusading and of the “Reconquest” were influential. In still other places, again in northern Europe but also Malta, the military orders—armed religious orders (most famously the Knights Templar)—set up independent, or virtually independent states dedicated to perpetual crusading. Participants A departing or returning crusader being embraced by his wife, from the Belval Priory, Lorraine, late 12th century (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nancy) Who went on crusade? From the beginning, popes and other leaders sought to encourage only professional men of war, whether kings, lords, knights, or simple men-at-arms, to go on crusade. And from the beginning, individuals of almost every other social class, age, and gender ignored this and wanted to go, too. The only people explicitly forbidden from going on crusade were those who had taken religious vows (like priests and monks), and even then, many tried to find a way to go—and, indeed, many went. This doesn’t mean that everyone in Europe was pulled inexorably into crusading like water down a drain. Crusading was expensive, and it was very risky. To go on crusade meant leaving your loved ones and your property (if you had any) vulnerable for at least several years and possibly forever. Going on crusade was not an “easy out” for younger sons (as used to be thought) nor was it a reliable treasure-hunting expedition; it impoverished many more people than it profited. Nonetheless, because of the spiritual and social rewards on offer for crusading, crusade leaders were never able to fully stop people of both genders and all classes from accompanying armed parties on crusade, and it is fair to say that many expeditions, especially those to the Levant, included a wide range of age, social classes, and military experience. Essay by Dr. Susanna Throop The impact of the crusades It is hard to summarize the impact of a movement that spanned centuries and continents, crossed social lines, and affected all levels of culture. However, there are a few central effects that can be highlighted. Military orders First, the earliest military orders originated in Jerusalem in the wake of the First Crusade. A miltary order is a religious order in which members take traditional monastic vows—communal poverty, chastity, and obedience—but also commit to violence on behalf of the Christian faith. Well-known examples include the Knights Templar (officially endorsed in 1129), the Knights Hospitaller (confirmed by papal bull in 1113), and the Teutonic Knights (originated in the late twelfth century). The military orders represented a major theological and military development, and went on to play central roles in the formation of key political units that still exist today as nation-states. Wall plaque, Ascalon, mid-twelfth to mid-thirteenth century. The Arabic inscription commemorates the wall built as defense against crusaders. The arms of Sir Hugh Wake (Lincoln, England) were later carved over that, confirming the 1241 crusader reconquest of the city. Territorial expansion Second, crusading played a major role in European territorial expansion. The First Crusade resulted in the formation of the crusader states in the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean), which were initially governed, and in small part populated, by settlers from Europe. Crusading in northern and eastern Europe led to the expansion of kingdoms like Denmark and Sweden, as well as the creation of brand-new political units, for example in Prussia. As areas around the Baltic Sea were taken by the crusaders, traders and settlers—mostly German—moved in and profited economically. In the Mediterranean Sea, crusading led to the conquest and colonization of many islands, which arguably helped ensure Christian control of Mediterranean trade routes (at least for as long as the islands were held). Crusading also played a role in the conquest of the Iberian peninsula (now Spain and Portugal). This was finally completed in 1492, when the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand II and Isabella I conquered the last Muslim community on the peninsula—the city of Granada. They expelled Jews from the country in the same year. And of course, they also authorized and supported the expeditions of Christopher Columbus, who—like many European explorers of his day—believed that the expansion of the Christian faith was one of his duties. Impact in Europe (religious and secular) Third, the crusading movement impacted internal European development in a few important ways. The movement helped both to militarize the medieval western Church and to sustain criticism of that militarization. It arguably helped solidify the pope’s control over the Church and made certain financial innovations central to Church operations. And it both reflected and influenced devotional trends. For example, while there was some dedication to St. George from the early Middle Ages, the intensity of that devotion soared in Europe after he reportedly intervened miraculously at the Battle of Antioch in 1098, during the First Crusade. Secular political theories were influenced by crusading, especially in France and the Iberian peninsula, and government institutions evolved in part to meet the logistical needs of crusading. Credit infrastructures within Europe rose to meet similar needs, and some locales—Venice, in particular—benefitted significantly in economic terms. It goes without saying that the crusades also had a highly negative effect on interfaith relations. Impact world-wide Fourth, the crusading movement has left an imprint on the world as a whole. For example, many of the national flags of Europe incorporate a cross. In addition, many images of crusaders in our popular culture are indebted to the nineteenth century. Some in that century, like the novelist Sir Walter Scott, portrayed crusaders as brave and glamorous yet backward and unenlightened; simultaneously, they depicted Muslims as heroic, intelligent, and liberal. Others more wholeheartedly romanticized crusading. George Inness, Classical Landscape (March of the Crusaders), 1850, oil on canvas (Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Massachusetts) These trends in nineteenth-century European culture impacted the Islamic world. Sometimes this influence was quite direct. In 1898 German Emperor Wilhelm II visited the grave of Saladin (Ṣalāḥ ad-Dīn Yūsuf ibn Ayyūb, a Muslim leader who led the recapture of Jerusalem in 1187) and was appalled at its state of disrepair. He paid to have it rebuilt, thus helping encourage modern Islamic appreciation of Saladin. Kaiser Wilhelm II, visit to Jerusalem, 1898 Sometimes the European influence was more diffuse. Modern crusading histories in the Islamic world began to be written in the 1890s, when the Ottoman Empire was in crisis. After the Ottomans, some Arab Nationalists interpreted nineteenth-century imperialism as crusading, and thus linked their efforts to end imperial rule with the efforts of Muslims to resist crusading in previous centuries. It would be reassuring to believe that nobody in the West has provided grounds for such beliefs, but it would not be true. Sadly, the effects of the crusading movement—at least, as it is now remembered and reimagined—seem to be still unfolding. Text by Dr. Susanna Throop