Document 14249905

advertisement

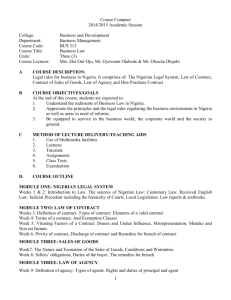

Journal of Research in Peace, Gender and Development (ISSN: 2251-0036) Vol. 1(9) pp. 242-248 October 2011 Available online@ http://www.interesjournals.org/JRPGD Copyright ©2011 International Research Journals Review An appraisal of readers’ comments on Olusegun Obasanjo’s (My Command): An account of the Nigerian civil war, 1967 - 1970 Joshua A. Abolaji Joseph Ayo Babalola University, Ikeji-Arakeji, P. M. B. 5006, Ilesa, Nigeria. E-mail: jabolaji@yahoo. Accepted 09 August, 2011 The aim of the paper is to examine how a book such as Obasanjo’s (My Command): An account of the Nigerian civil war, 1967 to 1970 has generated readership, controversy, comments and further promote interest about the history of the 1967 to 1970 civil war in Nigeria and also to provide a bibliography of relevant sources of information on the Civil War for would-be researchers, librarians, scholars and the general public. Following Obasanjo’s claim and allegation in the book that most of the soldiers who took part in the war were unruly and undisciplined, the author assembled the various comments and criticisms in various Nigerian newspapers as counter reactions. There is no doubt that the book is controversial, highly generative and thought to be subjective by critics and it could spur more books to be written in order to correct the wrongs that might have been fore grounded by Obasanjo thereby culminating in the production of literature about the war and promoting readership. Keywords: Olusegun Obasanjo, civil war, my command, Nigerian civil war, bibliography, appraisal. INTRODUCTION My Command: An account of the Nigerian Civil War, 1967 to 1970 (subsequently My Command...) by Olusegun Obasanjo was published by Heinemann Educational Books in 1980. Before My Command…, over sixty-nine books and pamphlets, fifty-three government publications, three bibliographies and two theses had been published on the 30 month long Nigerian Civil War that took place between 1967 and 1970. However, My Command… had so far been the most read and the most criticized by the Nigerian reading public. According to a paid advertisement by Heinemann on page 20 of Daily Sketch of November 28, 1980, all the copies of the first edition of the book were sold within 11 days of publication. Requests for more copies between th th the 11 day and the 14 day of publication were more than 3600. This had been described as a record in the history of publishing in Heinemann in particular and in Nigerian publishing in general for this class of book. It was also a landmark in Nigerian reading awareness. The serialization of the book by a newspaper, The Punch, which lasted 9 days beginning from October 30 had already whetted readers’ appetite before the book was launched by Chief Bola Ige, the then Governor of Oyo State of Nigeria on Saturday November 1, 1980. No sooner was the book launched than readers began to react to it on the radio and television, private discussions and also in newspaper interviews and articles. It was a credit to the author, the publishers, the booksellers, the reading public and the press at large that the book was accorded such a wide circulation and critical appraisal. It is strongly believed, therefore, that it would be unfair to these various organs, if the readers’ views and comments on the book are allowed to remain scattered on the pages of the various newspapers without putting them together in one volume for readers. Therefore, because of the keen interest the author of this paper has in My Command…, readers’ comments on the book in the press and other news media have been consistently followed since 1980. Moreover, because of the relative importance of the book and the comments on it on the history of Nigeria, the author of this paper aims to provide a short review of the readers’ comments on My Command…a list of the sixty-one articles and comments and the newspapers that contain their full texts [see pages 10 –13] and finally a select bibliography of materials that were published before My Command… Abolaji 243 (See pages 13 – 21). It appears as if General Obasanjo had predicted fireworks on his book, My Command… when he stated in the first paragraph of the introduction that “Most of the active participants on both the military and civilian sides are still very much alive and active making it possible for corrections and comments by participants referred to in the book.” Governor Bola Ige’s remark that “My Command… will open a flood-gate to controversy” at the launching ceremony of the book is therefore a confirmation of the author’s prediction. However, certain questions ought to be answered-Why did the book generate so much firework? Who were the gunners? How fair and accurate did they shoot? Did they overshoot their target? Did the victim (the author) expect so many fireworks? In the first place, one shares the opinion of Adedipe (1980: 3) that General Obasanjo had since 1975 plunged himself, by accident rather than by design, into the centre of a whirlpool constituted by the mass purge of public servants during the same year, when he was next-incommand to the Head of the State, his own policies as Head of State from February 1976 to October 1, 1979, especially the modus operandi with which the presidency of Nigeria was decided in 1979. He had in this manner created for him, though unwittingly, a group of critics who quickly rose up to ‘crucify’ him for whatever he wrote, said or did when he subsequently became a private citizen in October 1979. This situation was aggravated by the fact that he mentioned and made reference to the names of certain civilians and military officers in bad light. Such men who felt they had a reputation to defend naturally reacted, sometimes angrily, to his book. His critics included not only top military officers (both retired and serving officers) in the Nigerian Army, majority of whom had been discredited one way or the other by the author, but also politicians, especially those who believed that the General robbed them of the presidency of Nigeria in 1979, journalists, academics and the man on the street. Thirdly, the criticisms vary as much as the sorts and conditions of the critics. As we have stated earlier, some of the author’s colleagues in khaki uniform wrote to defend their names, even though some of them left the substance of what was specifically said about them to comment on general issues about the war. Some of the critics in this category challenged the accuracy and authenticity of the facts mentioned in the book. For example, Abisoye (1980: 7) asserted that the first shot of hostility rang out of the muzzle of a Biafran rifle contrary to what the author claims in the book. He also accused the author of making use of certain sources that were not accessible to him during the period covered by the book without acknowledging the sources. Some critics replied the author with posers instead of answering the charges that were leveled against them. Other critics like Haruna (1980: 5); Ejoor (1980: 5); Adebayo (1980: 1, 6); Adekunle (1980: 1) and Captain Francis Shanu (1980: 16) believed that the book was a potential grenade which could blow up the country; hence they called for its withdrawal from circulation. But such wolf-shouts were already too late the time they were made, judging by the number of copies that had been sold. Both military and civilian critics believed that the author was too egocentric and was all out to destroy his fellow participants in the war efforts in order to highlight his own fine points and glorify himself. There are a lot of facts in the book to justify this accusation. In the first place, officers were portrayed as unruly, undisciplined, outright indolent or intellectually bankrupt. For example, General Murtala Mohammed, the author’s erstwhile mentor and predecessor as Head of State, was accused on page 57 as undisciplined and unruly! Col. Ibrahim Haruna, who took over 2 Division from Murtala was accused of not being “prepared to make far reaching changes that were necessary and desirable to remould 2 Division into an effective fighting formation. He was therefore never able to achieve any significant success with the Division throughout his period of command which spanned fifteen months or so (see page 58 of My Command…). The General Officer Commanding (GOC) of the 1 Division was accused of being cautious slow, but less risk-taking. Brigadier Adekunle, the GOC of the 3 Marine Commandos was said to have pushed the morale of the soldiers of his command to its lowest ebb: “Desertion and absence from duty without leave was rife in the Division. The despondence and general lack of will to fight in the soldiers was glaringly manifest in large number of cases of self-inflicted injuries throughout the formation. Some officers tacitly encouraged these malpractices and unsoldierly conduct by condoning such acts or withdrawing their own kith and kin or fellow tribesmen to do guard duties in the rear and in the officers’ own houses” (Pages 56-57). General Ironsi is charged with being handicapped by his intellectual short-comings and that his advisers (who were also accused of been inward-looking) did not help him very much.[page6] Of the officer corps and the civilians in general, the author remarks: “Distrust and lack of confidence plagued the ranks of the officer corps. Operations were unhealthily competitive in an unmilitary fashion and officers openly rejoiced at each other’s misfortunes. With the restrictions imposed by the Federal Military Government on many items of imported goods and the country in the grip of inflation, the civilian population began to show signs of impatience with a war which appeared to them unending. In fact, some highly placed Nigerians started to suggest that the Federal Government should sue for peace at all costs to prevent 244 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. the disaster that would befall it and its supporters if rebel victory seemed imminent. This was the position when I was appointed the General Officer Commanding 3 Marine Commando Division of the Nigerian Army” (Page 57) all the ferries in use elsewhere in the country to Asaba. He had also embarked on special training of the brigade earmarked for the operation in conditions similar to where the actual operation would take place” (page 41). Praising his fellow officers the author states as follows: Against this background the author says the following thing about himself: “Within a space of six months I turned a situation of low morale, desertion and distrust within the Army into one of high morale, confidence, co-operation and success for my division and for the Army” (Page 68). Most of the critics, both military and civilians alike, condemned the author’s castigation of General Murtala. They wondered why he agreed to serve under Murtala when he [the author] knew that Murtala, according to him, was unruly and undisciplined. They were of the opinion that the author could not have said such a thing about General Murtala if he were alive. It is however encouraging that such critic rose up like one man to condemn the criticism which Obasanjo leveled against his former boss. This clearly shows that four years after the assassination of General Murtala, he still occupied a place of pride in the hearts of the people. The literary world has again risen up, as did the society at large, when the late hero was murdered in cold blood on February 13, 1976. Another criticism leveled against the author was that he has written on events outside his own command in a book titled My Command... It is unfortunate that many of the critics did not see anything good about the book, hence they only highlighted its weak points and on the basis of that condemned the whole book. Alfred Ilenre (1980: 4) remarks that the book depicts a hasty job which does not go beyond a crawling school boy exercise. A school principal stated that “apart from abuses and false stories, there is nothing in My Command… which a form III student cannot put down in writing and better.” Tola Adeniyi (1980: 3) is of the opinion that the author had put together pieces of stories from old newspapers and called the assemblage of the cuttings a book. The truth, however, is that most of the criticisms are more prejudiced than objective. It is also true that most of the author’s comments on his fellow soldiers were rather sarcastic and damaging but one wonders why many critics did not bother to mention that the author also sang certain songs of praises about his colleagues and other categories of people who contributed to the success of the war. Obasanjo incurred the greatest wrath from his critics by the uncomplimentary remarks he made about the late General Murtala Mohammed. But in his comments on General Murtala, the author says that: “The 2 Division Commanders had shown great determination, initiative and resourcefulness by collecting “It is pertinent to emphasize here that the previous commanders, from whom the three of us, the new commanders, were to take over, had been at the war front for periods ranging from fifteen to nearly twenty-two months. They had the difficult task of crossing the Rubicon as far as the Nigerian civil war was concerned. The situation under which they had carried out their task was less than ideal. The Federal procurement, supplies and provisioning system was not one to encourage or gladden the heart of a field commander in war. All the same the task of crushing rebellion was pursued with singleness of purpose. Mistakes were made as was to be expected of human beings operating human institutions. But by and large national interest was paramount” (Pages 63-64). Commending the effort of some medical personnel, Obasanjo has this to say: “I was highly impressed by the work of Dr. Nya and his staff. He was a quiet, unassuming and highly dedicated doctor. He was an asset to the division, working singlehanded night and day until [he was] joined by Major Ferrera, another indefatigable young doctor” (Page 69). With the foregoing encomium it is quite wrong to say that Obasanjo saw nothing good in his fellow military officers and civilians as some of his critics would want us to believe. It is encouraging, however, to note that a good number of the critics have not allowed themselves to be blindfolded by social or political prejudice hence they felt bold to mention some of the good points about the book. Bola Ige (1980: 6, 10) remarks that My Command… is the most authoritative account written so far about the prosecution of Nigeria’s 30-month long civil war, being the first account from an insider; that pages 65 to 145 of the book “are brilliant, naturally racy, descriptive, detailed…. and written with a good command of the English language.” In his well-balanced critique, Labanji Bolaji (1980:3) states that even a professor of history would be proud to be the author of the book. Ishola Kolawole (1980:5) believes that the book contains excellent information for the enrichment of knowledge for both young and old; “the contents are parts of our history” and the book is a story told in good time. Even in his flaming spit-fire on the book, Ebino Topsy (1980:12) believes that “there is no doubt that the book was brilliantly written.” In his own comments, E. C. Obano (1980:4) remarks that “General Obasanjo had done, not Abolaji 245 only what an army officer had never done, but also what our academics would find difficult to accomplish. He has produced a first class book on the civil war.” Also commenting on the academic quality of the book T. A. Fagbola (1980:4) states that the book has proved to the generality of the people that members of the Nigerian Army are not academic nit-wits or never-do-wells, but a good number of them are academic giants. Baffled by the academic brilliance of the work, a nameless commentator also wonders whether the author had not employed a ghost writer. CONCLUSION There is no doubt that the work had cleared any misconception which anyone might have had about the academic ability of members of the Nigerian Army. Moreover, the brilliantly written reactions of critics like David Ejoor, Ibrahim Haruna, and Emmanuel Abisoye, among others, had further proved the intellectual mettle of the Nigerian soldiers. There is no doubt that the author had received stinging and biting criticisms both from soldiers and civilians from all walks of life. Even though the author expected such reactions from his readers, it appears as if he had received more shots than he bargained for. It is worthy to note that the more controversial a book is, the more publicity and patronage it receives from the public. Moreover, the day a book is less critiqued or appraised the end has come to the book. An illustration could be drawn from Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses (1988). In the words of our elders, Obasanjo has burnt his hair and he has consequently learnt what his body smells like. His former position as Head of State has put him in a glass-house from where he should normally not throw stones. Unfortunately, he deliberately threw stones at his colleagues. Some of them threw heavier boulders at him in return from left, right and centre. Perhaps it is an instance of sowing the wind and reaping the whirlwind. Perhaps the greatest fault with the author is the style of writing and presentation of facts. As Sina Adedipe (1980:3) has rightly pointed out, most of the points for which the author had been taken to task are issues that people have heard about. For instance, he quoted certain sources like the Supreme Headquarters and Frederick Forsyth’s book The Biafra Story [pages 118-119] to support some of his claims. The things that were capable of generating offence could have been written in a discreet manner, particularly if he [the author] bore it in mind that he was like somebody who is wanted to be roasted for a feast and who should therefore not smear his body with palm oil and get close to a big fire. Finally, it is not unlikely that the author expected so many posers from his audience. Perhaps he should attempt to answer the posers. Such an attempt would no doubt result into another book which would also sell like hot cakes as My Command… did. REFERENCES Abisoye Emmanuel O (1980). Sympathy, Not Blame for Obasanjo, Daily Sketch, November 24, p. 7. Adebayo Adeyinka (1980). Adebayo Attacks Sege’s Book: It Can Tear this Nation, Daily Sketch, November 14, pp. 1&6. Adedipe Sina (1980). My Command, Sunday Concord, November 23, p. 3. Adekunle Benjamin (1980). My Command Will Set Us Ablaze, Daily Sketch, November 3, p. 1 Adeniyi Tola (1980). Obasanjo’s Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 8, p. 3. Bolaji Labanji (1980). Obasanjo’s Controversial Command, National Concord, November 23, p. 3. Ejoor David (1980). Restraint Please, Daily Sketch, November 12, 1980, p. 5. Fagbola TA (1980). Another Side to Obasanjo’s My Command, New Nigerian, December 17, p. 4 Forsyth Frederick (1969). The Biafra story. Baltimore: Penguin Books. Haruna Ibrahim B (1980). M. My Command Is a Danger to Peace, Daily Sketch, November 24, p. 5. Ige Bola (1980). My Command Will Generate Controversy, Sunday Sketch, November 2, p. 6&10. Ilenre Alfred (1980). My Command: the Betrayal of a Nation, Nigerian Tribune, November 20, p. 4. Kolawole Ishola (1980). My Command: Story Told In Good Time, The Punch, November 28, p. 5. Obano EC (1980). My Command: Dr Azikiwe Got It Wrong, New Nigerian, December 3, 1980, p. 4. Rushdie Salman (1988). The Satanic Verses. – New York: Viking Press. Shanu Francis (1980). “Ban My Command, Nigerian Observer”, November 12, p. 16. Topsy Ebino (1980). Obasanjo’s: My Command, Sunday Tribune, November 16, p. 12. BIBLIOGRAPHY Part I: Fireworks from Fellow Military Officers Abisoye, Emmanuel O. Sympathy, Not Blame for Obasanjo, Daily Sketch, November 24, 1980, p. 7. Adebayo, Adeyinka. Adebayo Attacks Sege’s Book: It Can Tear this Nation, Daily Sketch, November 14, 1980, pages 1 & 6. Adekunle, Benjamin. My Command Will Set Us Ablaze, Daily Sketch, November 3, 1980, p. 1 Adekunle, Benjamin. Obasanjo, Is a Liar, Daily Sketch, November 10, 1980, p. 24. Adenekan, Yinka. Obasanjo Should Be Condemned, Daily Sketch, November 14, 1980, p. 10. Ariyo, J. O. Ban My Command, Daily Sketch, November 13, 1980, Pages 1 & 16. Ejoor, David. Restraint Please, Daily Sketch, November 12, 1980, p.5. Haruna, Ibrahim B. M. My Command Is a Danger to Peace, Daily Sketch, November 24, 1980, p. 5. Isama, Godwin Alabi. My Command: It’s All Fiction, Daily Sketch, December 1, 1980, p. 16. Madiebo, Alexander. My Command Is Academic Disgrace, Daily Sketch, November 24, 1980, P. 16. Shanu, Francis. Ban My Command, Nigerian Observer, November 12, 1980, p. 16. Part II: Fireworks from the Generality of the People Abdulrahman, Yoonus. Obasanjo’s My Command, Nigerian Herald, November 17, 1980, p. 7. 246 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. Adebiyi, Johnson Olu. It is Our Command, Daily Sketch, November 11, 1980, p. 2. Adeniyi, Tola. Obasanjo’s Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 8, 1980, p. 3. Adesina, Lam. Striving After the Wind, Nigerian Tribune, November 19, 1980, p. 4. Ajibade, S. S. Ban That Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 18, 1980, p. 15. Allende, Olubanjo. Ban That Book, New Nigerian, November 22, 1980, p. 4. Aleyele, A. O. Obasanjo’s Memoir Is Too Early, Nigerian Observer, November 18, 1980, p. 5. Azikiwe, Nnamdi. Obasanjo Is Biased, Daily Sketch, November 18, 1980, p. 16 Braithwaite, Tunji. Obasanjo IS an Impostor, Nigerian Tribune, November 13, 1980, p. 9. Gbonegun, Arthur. One Man Protest, Daily Sketch, November 6, 1980, pages 1 and 24. Ibirogba, Olu Ade. My Command Disappoints Me, Daily Sketch, November 18, 1980, p. 2. Ilenre, Alfred. My Command: the Betrayal of a Nation, Nigerian Tribune, November 20, 1980, p. 4. Iyeru, Bunmi. My Command: Ha’ba Uncle Sege, Sunday Sketch, November 23, 1980 p. 5. Maidasawa, Nzida. My Command: Let’s Hear Other Versions of the Civil War, New Nigerian, November 22, 1980, p. 4. NMEZI, Innocent. Ban My Command, National Concord, November 27, 1980, p. 5. NOSIRU, B. O. General Obasanjo: A Saint or What, Daily Sketch, November 15, 1980, p. 2. OBADINA, Tunde. General Obasanjo: Hero by Default, The Punch, November 21, 1980, p. 5. ODETOLA, Wole. Wole Condemns My Command, Daily Sketch, November 6, 1980, pages 1 and 17. OFOEGBU, J. Obasanjo’s Book Is Malicious, Nigerian Tribune, November 27, 1980.p. 5. OGUNDELE, Banji. Later My Command, Sunday Tribune November 9, 1980, p. 7. OGUNDELE, Banji. My Command, Sunday Tribune, November 16, 1980. P. 7. OGUNSOLA, Layi. My Command, Sunday Tribune, November 9, 1980, p.4. OLOYEDE, BISI. Adesanya Condemns Obasanjo’s Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 12, 1980, p. 16. OLU, Ogidi. Question Mark on My Command, Nigerian Tribune, December 19, 1980, p. 2. OSIBERU, Solomon Adetunji. My Command: A Worthless Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 8, 1980, p. 5. OVUEHOR, Jimmy. Reflections on the General’s Memoir, Nigerian Observer, November 6, 1980, p. 5. SANNI, Agboola. My Command: A Socio-Political Appraisal, Sunday Tribune, November 23, 1980. SOLARIN, Tai. No Secret Meeting With Obasanjo, Daily Sketch, November 6, 1980, p. 1. SOLARIN, Tai. Obasanjo Set to Destroy, Daily Sketch, November 4, 1980, p. 16. STRIP Obasanjo of All Honours. Nigerian Tribune, November 20, 1980, p. 5. TAHIR, Mouktar. Ahmed My Command: the Missing Link, Nigerian Tribune, November 20, 1980, p. 5. TAHIR, Mouktar Ahmed. Re-probe Ramat’s Death, Sunday Sketch, November 16, 1980, p. 16. TOPSY, Ebino. Obasanjo’s: My Command, Sunday Tribune, November 16, 1980, p. 12. Part III: Sympathetic Views AJIBOYE, Adejare. My Command Is A Success, Nigerian Herald, November 22, 1980, p. 2. DEJI, A. My Command and Critics, Daily Times, December 17, 1980, p. 15. FAGBOLA, T. A. Another Side To Obasanjo’s My Command, New Nigerian, December 17, 1980, p. 4 JEKADA, Mohammed. General Haruna’s Commentary on My Command, New Nigerian, December 25, 1980, p. 5. KOLAWOLE, Ishola. My Command: Story Told In Good Time, The Punch, November 28, 1980, p. 5. LET My Command Circulate, Daily Sketch, November 14, 1980, p. 1. MY Command Controversy. The Punch November 17, 1980, p. 5. NJOKU, Japhet C. Don’t Ban Obasanjo’s War Story, New Nigerian, November 22, 1980, p. 4. OBANO, E. C. My Command: Dr Azikiwe Got It Wrong, New Nigerian, December 3, 1980, p. 4. OLAYANJU, Kunle Olu. The Fault with My Command, Nigerian Tribune, November 25, 1980, p. 5. OPARA, H. B. Obasanjo’s Book, Nigerian Tribune, November 27, 1980, p. 4. READ My Command, Don’t Burn It, Nigerian Herald, November 17, 1980, p. 5. Part IV: Balanced Appraisal ADEDIPE, Sina. My Command, Sunday Concord, November 23, 1980, p. 3. BOLAJI, Labanji. Obasanjo’s Controversial Command, National Concord, November 23, 1980, p. 3. IGE, Bola. My Command Will Generate Controversy, Sunday Sketch, November 2, 1980, Pages 6 and 10. OBASANJO’S Command. Nigerian Tribune, November 26, 1980, p. 3. WILLIAMS, Ebenezer. My Command: Our Hero Worships Himself, National Concord, November 24, 1980, p. 3. A Select Bibliography of Books, Government Publications, Theses and Bibliographies Published (Before My Command…) on the Nigerian Civil War that took place between 1967 and 1980. MONOGRAPHS ACHEBE, Chinua. Girls at war and other stories. London, Heinemann, 1972. AKPAN, Ntieyong Udo. The struggle for secession, 1967–1970; a personal account of the Nigerian civil war. London, F. Cass, 1977, 225p. ALADE, R. B. The broken bridge: reflections and experiences of a medical doctor during the Nigerian civil war. Ibadan, Carton Press, 1975. AMADI, Elechi. Sunset in Biafra: a civil war diary. London, Heinemann, 1973. AMALI, Samson O. Ibos and their fellow Nigerians. Ibadan, 1967, 55p. ANTONELLO, Paola, Nigerian gegen Biafra…. by Paola Antonello and others, Berlin, Wagenbach. 160p. ARMAND, Captain. Biafra vaincra: Paris, Editions France-Empire, 1969, 268p. ARMSTRONG, Robert G. The issues at stake in Nigeria, 1967. Ibadan, Ibadan University Press, 1967. 19p. ATILADE, E. A. The history of Nigerian civil war in poems. Lagos, New Nigeria Press, 1970. 24p. AWOLOWO, Obafemi. Lecture on the financing of the Nigerian civil war: its implications for the future economy of the nation. Ibadan, Geographical Society and Federalist Society of Nigeria, University of Ibadan, 1970. 32p. AZIKIWE, Nnamdi. Military revolution in Nigeria. London, Hurst, 1973. BALOGUN, Ola. The tragic years: Nigeria in crisis, 1966 – 1970. Enugu, Ethiope Pub. Corporation,1973. BONNEVILLE, Floris de Mortu du Biafra. Paris, R. Sola, 1968. 143p. BREWIN, Andrew. Canada and the Biafran tragedy by Andrew Brewin and David McDonald. Toronto, James Lewis and Samuel, 970. 173p. BRITAIN-BIAFRA Association. Biafra- Britain in the dock. [n.d.] 4p. BUHLER, Jean, Biafra: Tragodie eines begabten volks. Zurich, Flamberg Verlag, 1968. Abolaji 247 BUHLER, Jean. Tuez-les tous: Guerre de secession au Biafra. Paris, Flammarion, 1968. 240p. CERVENKA, Zdenek. The Nigerian war, 1967 – 1970; history of the war. Selected bibliography and documents Frankfurt am Main, Bernard & Graefe, 1971. 459p. CHOME, Hules .Le Drame du Nigeria. Waterloo, Belgique: Tiers-Monde et Revolution, 1969. 79p. CHRISTIAN Council of Nigeria. Christian concern in the Nigerian civil war: a collection of articles which have appeared in issues of the Nigerian Christian from April 1967 to April 1969. Ibadan, Daystar Press, 1969. 136p. COLLIS, Robert J. M. Nigeria in conflict. London, Secker and Warburg, 1970. xiii, 215p. CRITHLEY, Julian. The Nigerian civil war; the defeat of Biafra. London, Atlantic Information Centre for Teachers, 1970. 27p. CRONJE, Suzanne. The world and Nigeria; the diplomatic history of the Biafra war, 1967 – 1970. London, Sidgwick and Jackson, 1972. xii 409p. DE ST. Jorre, John. The Nigerian civil war.”London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1972. 437p. DEBRE, Francois. Biafra, an II. Julliard, 1968. 219p. FORSYTH, Fredrick. The Biafra Story. Harmondaworth, Middlesex, Penguin Books. 1969. 236p. GOLD, Berbet. Biafra goodbye. San Francisco, Two Windows Press, 1970. 45p. HANISCH, Rolf. Burgerkrieg in Africa? Biafra und die inneren Konflikte eines Kontients. Berlin, Coloquium Verlag, 1970. 78p. HENTSCH Thierry. Face au blocus. La Croix-Rouge international dans le Nigerian en guerre (196701970). Geneve, Institute Universitaire de hautes etudes internationals, 1973. HUNT, David. On the spot: an ambassador remembers. London, Peter Davies, 1975. xi, 259p. IKE, Vincent Chukwuemeka. Sunset at dawn: a novel about Biafra. London, Collins and Harvill Press, 1976. JUNKER, Helmut. Hunter den Fromten also Arzt in Biafra. Wursburg, Arena, 1969. 264p. KIRK-CREENE. Anthony Hamilton Millard. Crisis and Conflict in Nigeria; a documentary source book, 1966 – 1969. London, Oxford University Press, 1971. 2vols. MADIEBO, Alexander A. The Nigerian revolution and the Biafra war. Enugu, Fourth Dimension, 1980, xii, 411p. MARKPRESS. New Feature Service, Press Actions, abridged ed., covering periods Feb. 2 to Dec. 31, 1968; Jan, 1 to June 30, 1969 and July 1 to Dec. 31 1969. 1968 – 69. 3vols. MOK, Michael. Biafra journal: a photographic account of the Nigerian civil war. 1969. 96p. NIGERIA et Biafra, au Carrefour des options. Paris, S. I. P. E., 1968, 78p. NWANKO, Arthur Agwuncha. Nigeria: the challenge of Biafra. London Rex Collins, 1972. NWANKO, Arthur Agwuncha. The making of a nation: Biafra by Arthur Agwuncha Nwankwo and Samuel Udockukwu Ifejika, 1969. Xii, 361p. NWEN, Sir Rex. The war of Nigerian unity, 1967 – 1970. Ibadan, Evans Bothers, 1970. vii, 175p. OBE, Peter. Nigeria: a decade of crises in pictures. Lagos, Peter Obe Photo Agency, 1971. 20p. OHONBAMU, Obarogie. The psychology of the Nigerian revolution. Ilfracombe, Stockwell, 1969. 224p. OJUKWU, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu,. Biafra selected speeches and random thoughts of C. Odumegwu Ojukwu, General of the people’s army, with diaries of events. New York, Harper & Row, 1969. 387p. 226p. OJUKWU, Chukwuemeka Odumegwu. Selected speeches by Paddy Obi Nwadishi. Onitsha, New Era Printers [n.d.] 66p. OKEKE, Godfrey Chukwugozie, The Biafra–Nigeria war: a human tragedy. London, 1968. 30p. OKOH, Gim, Nigerian: Its politics and the civil war. 1968. 16p. OPAKU, Joseph, ed. Nigeria: dilemma of nationhood; an African analysis of the Biafra conflict. West port, Conn., Greenwood Press, 1972. 426p. OYEWOLE, Fola. Reluctant rebel. London, Rex Collins, 1975. 210p. OYINBO, John. Nigeria: crisis and beyond. London, C. Knight, 1971. 214p. RAJIH, S. A. The complete story of Nigeria civil war for unity 1966 – 1970 and current affairs. Ontisha, Biafra: naissance d’une nation? Paris, Aubier-Montaigbe, 1969. 255p. ROSEN, Carl Gustaf von. Biafra-som jag ser det. Stockholm, Wahlstrom & Widstrand, 1969, 104p. ROSEN, Carl Gustaf von. Le ghetto Biafras tel que je l‘ai vu.Paris, Arthaud, 1969. 204p. SANTOS, Eduardo Dos. Vida e morte do Biafra.Lisboa, Sociedade de Expansao Cultural 1970. 235p. SCWAB, Peter ed. Biafra edited by Peter Schwab. New York, Facts on File, 1971, ii, 142p. SOSNOWSKY, Alexandre. Biafra: proximate de la mort continuite de la vie. Paris, A. Fayard, 1969. STEINER, Rolf. Carre rouge, du Biafra au Soudan, Le dernier condottiers; recit recueilli par Yves – Guy Berges. Paris, Editions Robert Laffont, 1976. 452p. SULLIVAN, John R. Breadless Biafra. Dayton, Ohio, Pflaum Press, 1969. 104p. UNONGO, Paul Iycrpuu,. Say it loud, we’re black and strong; a new dawn for Nigeria, the hope and pride of the blackman. Lagos, Micho Commercial Printers, 1970, 101p. UWECHUE, Ralph. Reflecting on the Nigerian civil war: a call for realism; London, O. I. T. H. International Pub., 1969. 190p. UWECHUE, Ralph, Reflecting on the Nigerian civil war: facing the future. New revised and expanded ed. Paris Jeune Afrique, 1971 xii, 206p. UWECHUE, Raph. Lawerir du Biafra une solution Nigeriane. Paris Jeune Afrique,1969, 161p. WALLSTROM, Rord. Biafra; med efterskrift av Thomas Hammarberg. Stockholm, Bokforlaget, 1968. 120p. WAUGH, Auberon, Biafra: Britain’s shame by A. Waugh and S. Gronje. 1969. WAUGH, Auberon. Britain and Biafra; the case for genocide.1969. Wolf, Jean. La guerre des rapeaces: la verite sur la guerre du Biafra. Par J. Wolf et C. Brovelli. Paris, A. Michael 1969. 286p. GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS ASIKA, Ukpabi. End of war broadcast by the Administrator for East Central State Mr. Ukpabi Asika over former Radio Biafra at ObodoUkwu, Orlu on 16/1/70 at 8.45 p.m. 15p. Asika, Ukpabi. No victors; no vanquished: opinions, 1967 – 68 vol. 1. Enugu: East Central State Information Service, 1968. 80p. ASIKA, Ukpabi. Reflection on the political evolution of one Nigeria; a text of the public lecture delivered by His Excellency Ukpabi Asika on the occasion of the ceremony to launch the publication “No Victors, no vanquished. Enugu: 969. 10p. ASIKA, Ukpabi. Special appeal broadcast as a public service to the Biafran soldiers by the Administrator of the East Central State on December 14, 1968. ASIKA, Ukpabi. Speech delivered by His Excellency Mr. Ukpabi Asika, Administrator of the East Central State on the occasion of the visit to Enugu of Rt. Hon. Harold Wilson… 28 March 1969. 2p. AZIKIWE, Nnamdi. Origins of the Nigerian civil war. Lagos, Govt. Printer, 1969. 17p. BARRETT, Lindsay. A message to black activits on the Nigerian crisis. Enugu, Publicity Division, Ministry of Information 1969. 10p. BIAFRA, Ministry of Information. The concept of territorial integrity and the right of Biafrans to self determination. Enugu, Govt. Printer. East Central Sate Rehabilitation Commission. Conference on state-wide rehabilitation, reconstruction and reconstruction through community effort. September, 1969. Enugu, Government Printer, 1969. 60p. ENAHORO, Anthony. Framework for settlement; the Federal case in Kampala; Kampala Peace Talks opening statement. Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of information, 1968. 18p. ENOUGH is enough: a challenging appeal to the Ibos of Nigeria. Lagos, 1967. 16p. GOVERNMENT Statement on the current Nigerian situation. Lagos ,Printing Division, Ministry of Information, 1969. 5p. GOWON, Yakubu. Ending the fighting: broadcast to the nation by His 248 J. Res. Peace Gend. Dev. Excellency Major-General Yakubu Gowon; ending the war: the last lap. Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of Information,1968. 10p. GOWON, Yakubu, Long live African unity: address by His Excellency Major-General Yakubu Gowon… at the Assembly of Heads of Sate of the O. A. U. at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on Saturday. September 6, 1969. Apapa. Nigeria National Press, 1969. 8p. GOWON, Yakubu. Peace, stability and harmony in post-war Nigeria; Major-General Yakubu Gowon addresses World Press 5 January, 1968. Lagos, Ministry of Information, 1968. 10p. GOWON, Yakubu. Sacrifice for unity: New Year [1969] message by Major-General Yakubu Gowon, Lagos, 1969, 6p. GOWON, Yakubu,. The dawn of lasting peace: broadcast to the nation by Major-General Yakubu Gowon… 31 March, 1968. Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of Information, 1968. 7p. GOWON, Yakubu. Welcome address to the O. A. U. Consultative Mission by the Head of the Federal Military Government… Majorrd General Yakubu Gowon, 23 November, 1967. Lagos, 1967, 11p. GREAT Britain. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Report of the observer team to Nigeria 24 September to 23 November, 1968. London, H.M.S.O. 1969. 34p. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information, Ibos in a united Nigeria. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information. Nigeria answers question. Lagos, 1969. 13p. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information. Nigeria: the dream empire of a rebel? Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of Information, 1968. 21p. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information. The struggle for one Nigeria. Lagos, 1967. 59p. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information. Towards one Nigeria, nos. 1– 4. Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of Information, 1967. 4. vol. NIGERIA, Federal Ministry of Information. Unity in diversity. Lagos, 1967. 15p. NIGERIA, Mid-West, Department of Internal Affairs and Information. Midwestern State one year after liberation. Benin City, 1968. 32p. NIGERIA, Mid-West, Department of Internal Affairs and Information. The Nigerian crisis and the Mid-West decision. Benin City, n.d. 47p. NIGERIA, Mid-West, Department of Internal Affairs and Information. Understanding the Nigerian crisis. Benin City, 1968. 34p. NIGERIA, Mid-West Tribunal of Inquiry into Rebel Activities, Daily proceedings Days 1 – 142, 17 November, 1967 – 28 September, 1968. Benin City, Govt. Printer, 1967 – 68. NIGERIA, Public Service Commission. Re-absorption of former civil servants and the appointment of Central-Eastern State indigenes in the Federal Public Service of the Federation. Lagos, Printing Division, Ministry of Information, 1970. 22p. NIGERIA, Rivers State, Liberation diary. Port Harcourt. Govt. Printer, [n.d.] 6p. NIGERIA, River State. Rehabilitation Commission, Rehabilitation in the Rivers State. Port Harcourt, 1968. 24p. ORGANISATION of African Unity Consultative Mission to Nigeria, Report. Apapa, Nigerian National Press, 1967. 36p. ORGANISATION of African Unity Observers in Nigeria. No indiscriminate bombing; report on activities of the representatives of Canada, Poland, Sweden and the United Kingdom during the period th th 14 Jan – 6 March, 1969. Lagos, 1969. 26p. ORGANISATION of African Unity Observers in Nigeria. No genocide; th th final report of the first phase from 5 October to 10 December 1968. Lagos, Ministry of Information, 1968. 34p. RADIO Nigeria Lagos. Voices of unity [newstalks contributed to and broadcast over Radio Nigeria]. Apapa, Nigerian National Press, 1969. 45p. REHABILITATION to-date, Enugu, East Central State Commission for Rehabilitation. 1970 - . Monthly. TANZANIA, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Full Statement by Tanzania on the recognition of Biafra. Dar-es-salaam, 1968.5p. C. THESES ORISO, Michael A. International arms and Nigerian civil war, 1967 -70. 1978 iii, 73 leaves. M.Sc. Thesis submitted to University of Ife. THRUMBULL, Charles Perry. The Soviet Union and the Nigerian civil war: policy, ideology and propaganda. 1973. Ph.D. Thesis submitted to University of Notre Dame. Photocopy of typescript. Ann Arbor. Mich. University Microfilms, 1974. D. BIBLIOGRAPHIES AFFIA, George B. Nigerian crisis, 1966-1970; a preliminary bibliography. Lagos, Yakubu Gowon Library, University of Lagos, 1970. 24p. AGUOLU, Christian Chukwuenedy. Nigerian civil war, 1967 – 1970; an annotated bibliography. Boston, Mass., Hall, 1973. xx, 181p. OLAFIOYE, A. Olu. Nigerian civil war: index to foreign periodical articles. Lagos, National Library of Nigeria, 1972.