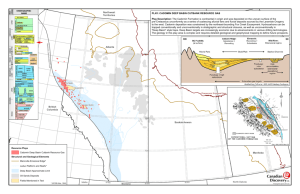

Views from the Upper San P edro River Basin:

advertisement