Audit Committee Independence and its Impact on the Occurrence of Fraud

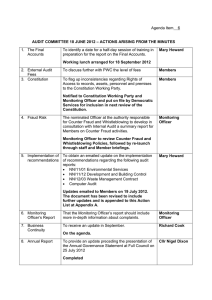

advertisement

Audit Committee Independence and its Impact on the Occurrence of Fraud Rusty Peterson Graduate Student University of Oklahoma ACCT 6193 Research Proposal December 16, 2002 http://students.ou.edu/P/Rusty.K.Peterson-1/Final%20Proposal.doc EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This proposed study examines the relation between the composition of firms’ audit committees and the likelihood of an existing financial fraud. Prior research by Klein (2002) provides evidence that audit committee independence increases with board size and board independence and decreases with the growth opportunities and for firms that report consecutive losses. Using a logistic regression model, I expect to find that the lower the level of audit committee independence for higher growth firms and for firms with sustained losses results in higher incidences of financial fraud. The results have implications for standard setters, regulators, the accounting profession, and the business community. I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND The role of audit committees continues to be important to regulators, the accounting profession, and the business community. In 1999, the SEC called on the Blue Ribbon Committee (BRC) to find ways of improving the effectiveness of corporate audit committees in overseeing the financial reporting process. Recently, President George W. Bush signed into legislation the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, which brought about rules that increase the responsibilities of audit committees, managers, and public accounting firms. Specifically, the legislation established that audit committees shall maintain independence from management and establish procedures for the “receipt, retention, and treatment complaints” received by the client regarding accounting, internal controls, and auditing [AICPA (2002)]. In addition, the AICPA has asked its members to help design antifraud programs and controls to be implemented by corporations and CPAs. This proposed study examines whether the level of audit committee independence for higher growth firms and firms with sustained losses result in higher incidences of financial fraud. 2 “Statement on Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 82, Consideration of Fraud in a Financial Statement Audit, distinguishes fraud from error on the basis of whether the underlying action that results in a misstatement of the financial statements is intentional or unintentional. The SAS notes that, while fraud is a broad legal concept, the auditor’s concern with fraud specifically relates to fraudulent acts that cause a material misstatement of the financial statements” [POB (2000)]. Fraud can include intentional misstatement of recorded amounts by employees, ordinarily accompanied by theft of company assets, intentional overstatement of recorded assets, understatement of recorded liabilities, or use of improper accounting methods with the intent of overstating a performance measure [Kinney (2000)]. Consistent with views of the Panel on Audit Effectiveness, “The primary responsibility for the prevention and detection of fraud rests with management, boards of directors and audit committees. Directors and audit committees should oversee management’s activities and demonstrate a strong commitment and involvement when problems arise.” Therefore, I believe that using audit committee independence, as a measure of corporate governance will provide insight to the occurrence of financial fraud. To establish a systematic approach for detecting fraud, I will use public records of firms subject to 10b-5 litigation from 1991 to 2000, Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases (AAERs) from 1982 to 2000, and firms subject to regulation under Accounting Series Release (ASR) No. 177 from 1991 to 2000. II. PRIOR LITERATURE AND EMPIRICAL PREDICTION Extant research by Klein (2002) provides evidence of economic determinants behind differences in audit committee independence, which I will adopt and explain in my empirical research. “Regulators currently view gray directors more like insiders than independent directors” [Carcello and Neal (2000)]. Carcello and Neal (2000) found that the greater the 3 percentage of affiliated directors on the audit committee, the lower the likelihood of goingconcern reports for financially distressed companies. According to Klein (2002) and Beasley (1996), the likelihood of fraudulent financial reporting increases with board size. This suggests that smaller audit committees could be more effective than larger committees. If this assertion is true, audit committee size might be associated with the incidence of fraud for financially distressed companies, which supports my second hypothesis. Prior studies report that overall, financial statements are less value-relevant for firms suffering repeated losses than for profitable firms. Klein (2002) suggests that, “Shareholders of firms with past consecutive losses demand less scrutiny of the financial reporting system and, consequently, have a lower demand for audit committee independence.” Consistent with the Blue Ribbon Committee and prior studies (e.g., Carcello and Neal 2000, Klein 2002), I assume that audit committee members who are independent of management are better monitors of the firm’s financial accounting process. In addition, “Benefits of effective monitoring include transparent financial statements, active trading markets, and the ability to use unbiased financial accounting numbers as inputs into contracts among shareholders, senior claimants, and management” [Klein (2002)]. This hypothesis may be stated as: H1: There is higher incidence of financial fraud when a firm’s audit committee lacks independence when compared to independent audit committees. As mentioned in the Panel on Audit Effectiveness Report, the motivation to manage earnings comes in part from management’s responsibility to direct the entity’s operations in a way that achieves targeted results. Both external and internal pressures can be derived from capital markets, whether from Wall Street’s expectations or from stakeholders’ expectations. Since there are incentives for managers to manipulate financial statements, I predict that 4 companies experiencing financial distress are more likely to commit fraud because they have difficulty in complying with debt agreements, such as missed payments or covenant violations. They also struggle to meet earnings targets, which leads to a second hypothesis: H2: There is higher incidence of financial fraud among financially distressed firms than among non-financially distressed firms. III. METHODOLOGY Since I am interested in identifying the factors that influence the probability of financial fraud, I must estimate a function of a set of explanatory variables. Suppose audit committee independence is an independent variable measuring fraud. If I were to use ordinary least squares regression, I would be looking for the estimated probability of fraud; however, in this study I am more interested in how the occurrence of fraud changes in response to changes in the explanatory variables. Thus, I will present a logit model of financial fraud as follows: FRAUD = b0 + b1FINDIST + b2GROWTH + b3AUDOUT + b4SARBOX + b5IPO + Fraud is a binary variable equal to one if a firm commits financial fraud and zero otherwise. Using dummy explanatory variables for FINDIST, GROWTH, and SARBOX, the observed values of the independent variables will be either one or zero. FINDIST will be one if a firm is financially distressed and zero if not. GROWTH will be one if a firm has growth opportunities and zero otherwise. SARBOX will be one if a firm’s CEO and CFO are required to certify their financial statements by the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, zero otherwise. AUDOUT and IPO are continuous variables and will have different values for each observation. The AUDOUT variable will be calculated from a logistic regression model used in Klein (2002): %AUDOUT = + 1Board Size + %Outsiders + 3Growth Opportunities + 4Losses + 5Debt-to-Assets + 6CEO on Compensation Committee 5 + 75%Blockholder on Audit Committee + 8%Outside Director Holdings + 9Firm Size + . (2) The IPO variable will represent how many years the observation is past the firm’s initial public offering. Each slope coefficient represents the change in the log of the odds of having fraud with respect to a one-unit increase in an explanatory variable, controlling for the effects of the other variables in the model. The signs of the slope coefficients indicate the direction of the change in the probability with respect to the change in the explanatory variable. Furthermore, variables with positive signs will increase the log of the odds of the dependent variable occurring and the converse is true for variables with negative signs. I will test the critical values of the t-statistics at a 95 percent confidence level. Sample Selection The analyses will be performed on three samples of firms having Big 5 auditors in result of the fact that Big 5 firms audit most of the SEC registrants. I will split all three samples into firms that are financially distressed and those that are not. The “shareholder lawsuit” sample, as taken from Francis et al. (1994), will consist of firms that were or are targets of 10b-5 litigation during the period January 1991 to September 2000. Section 10b-5 of the 1934 Securities Exchange Act makes it unlawful to “employ any device, scheme, or artifice to defraud…to make an untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made…not misleading…or engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.” The source of these data will be the Securities Class Action Alert and the financial data of these companies will be obtained from Compustat. 6 The “SEC action” sample will consist of firms subject of AAERs by the SEC filed between 1982 and 2000. Consistent with Bonner et al. (1998) and Carcello and Palmrose (1994), the sample might be reduced of firms that contained audit problems but no alleged financial reporting problems, firms that forged audit opinions, firms that were involved with misleading press releases, or companies for which no financial statement information can be obtained. This proxy is intended to capture circumstances at the fraud end of an errors-to-fraud continuum [Bonner, Palmrose and Young (1998)]. “One significant advantage to focusing on SEC enforcement actions is that these actions are an objective criterion for identifying companies with fraudulent financial reporting. Furthermore, the SEC often describes in an AAER the nature of the fraud” [Bonner, Palmrose and Young (1998)]. The “ASR regulation” sample will consist of firms with year-end restatement of previously issued quarterly financial statements. This sample will examine the details pertaining to firms that corrected earnings under the SEC’s Accounting Series Release (ASR) No. 177 from 1991 through 2000. “ASR No. 177 regulates correction of errors in quarterly earnings of public firms that are discovered by the time of the annual report” [Kinney and McDaniel (1989)]. Kinney and McDaniel (1989) find that “Common characteristics of firms that restate quarterly financial statements include firms listed over-the-counter, smaller, less profitable, more highly leveraged, and slower growing firms. Also, the corrections typically reduce earnings originally reported and the magnitude of errors appear high relative to traditional rule of thumb measures of materiality.” The Worldscope database will be searched for 1991 through 2000. The search criteria will be for words in close proximity to errors, corrections, revisions, or restatements within a footnote or segment that references either quarterly or interim information. 7 IV. RESULTS AND SIGNIFICANCE The proposed results will add to the broad scope of audit effectiveness research and provide insight into the debate over audit committee composition. Practitioners can benefit through a better understanding of the current environment, which may allow for better implementation of self-regulation. The expected results will provide evidence that firms with independent audit committees play a more effective role in corporate governance. I anticipate the finding that financially distressed firms lack audit committee independence and thus experience a higher occurrence of financial fraud than do firms in fiscal solace. Finally, this study is intended to be useful for accounting professors through promoting future research in the area of corporate governance. TIME BUDGET / COST BUDGET Hours Dollars Data Collection 20 325 Data Analysis 50 500 Paper Composition 50 250 Submit to Journals 40 500 Final Composition 40 200 Total 200 1,775 8 REFERENCES American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA). 2002. Summary of Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. New York, NY: AICPA. Bonner, Sarah E., Zoe-Vonna Palmrose, and Susan M. Young. 1998. Fraud Type and Auditor Litigation: An Analysis of SEC Accounting and Auditing Enforcement Releases. The Accounting Review 73 (4): 503-532. Carcello, Joseph V. and Terry L. Neal. 2000. Audit Committee Composition and Auditor Reporting. The Accounting Review 75 (4): 453-467. Crown, William H. 1998. Statistical Models for the Social and Behavioral Sciences: Multiple Regression and Limited-Dependent Variable Models. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. Francis, Jennifer, Donna Philbrick, and Kathernie Schipper. 1994. Shareholder Litigation and Corporate Disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research 32 (2): 137-164. Kinney, William R. Jr. 1994. Audit Litigation Research: Professional Help is Needed. Accounting Horizons 8 (2): 80-86. Kinney, William R. Jr. 2000. Information Quality Assurance and Internal Control for Management Decision Making. United States of America: McGraw-Hill Co. Kinney, William R. Jr. and Linda S. McDaniel. 1989. Characteristics of Firms Correcting Previously Reported Quarterly Earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11 (1): 7193. Klein, April. 2002. Economic Determinants of Audit Committee Independence. The Accounting Review 77 (2): 435-452. The Public Oversight Board (POB). 2000. The Panel on Audit Effectiveness Report and Recommendations. Stamford, CT: 75-98, 223-228. 9