Does globalization affect growth? Evidence from a new index of globalization

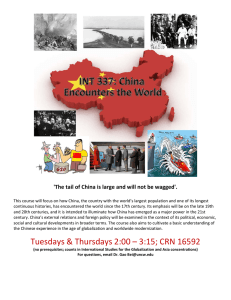

advertisement