Social Science Docket

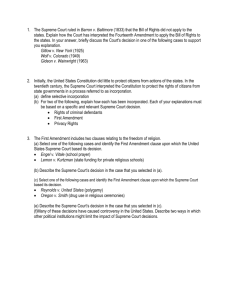

advertisement