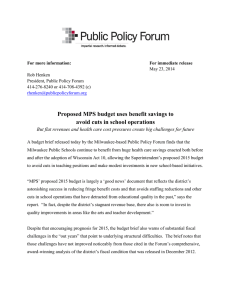

FOURTH-YEAR REPORT MILWAUKEE PARENTAL CHOICE PROGRAM

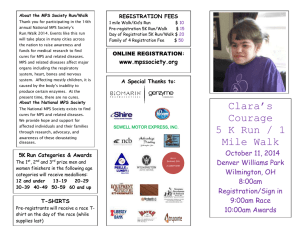

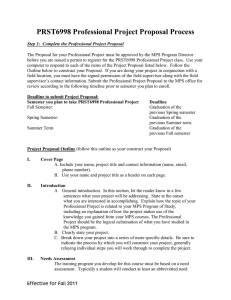

advertisement