Document 14204864

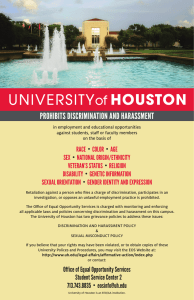

advertisement