Improving the Effectiveness of Wisconsin’s Comprehensive Planning Legislation by

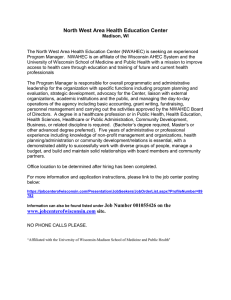

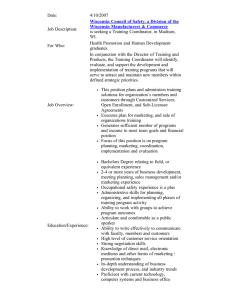

advertisement