Complying with Act 141: Renewable Electricity Consumption at State Facilities

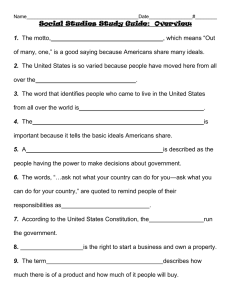

advertisement